In August 2018, more than a hundred Members of Parliament petitioned for a strict two-child policy in India. The reason being the country's ever-growing population, which is slated to touch 1.7 billion by 2050, and which would put immense pressure on resources.

Experts, however, think that coercion shouldn't even be the last resort as a means to control population. And even before the crisis of population explosion, comes the urgent need for strengthening sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), the solution to which lies in improving the practice of contraception.

India’s biggest population group lies in the 17-21 age bracket as of today, near its reproductive activity. If the prevalence and right use of contraception is not increased now, it will not bode well for the public health of a large populace. But where does India stand today?

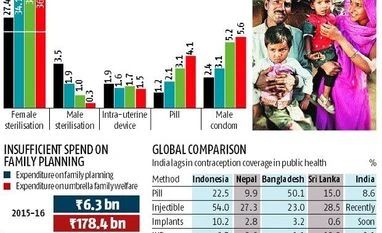

Firstly, the prevalence of (male) vasectomies in India declined from 3.5 per cent in 1992-93 to 0.3 per cent in 2015-16, even though male sterilisation is simpler and cheaper than that for women.

Secondly, of the budget earmarked for family welfare by states and the Centre, only four per cent is spent on family planning, according to data maintained by the Population Foundation of India (PFI).

Thirdly, the newest and most advanced contraceptives available in the market enter the public health system with a greater lag as compared to our immediate neighbours. This is something that could be pinned down to supply-side problems.

Finally, and most importantly, myths about contraception among men, ignorance about which contraceptive method best suits a person, and the taboo around sex and birth control are the demand side issues that threaten an organic existence of healthy and prudent practice of contraception in India.

“Failure to provide adolescents with appropriate methods will be a missed opportunity for reducing the incidence of unwanted pregnancy and its negative consequences,” the Advocating Reproductive Choices (ARC) Coalition, a family planning advocacy said in a statement on the eve of World Contraception Day.

Fall in fertility rate not deep enough

The “total fertility rate”, defined as the average number of children a woman would have, stands at 2.2 children, and is higher than the “wanted fertility rate” of 1.8 children per woman. This indicates that Indian couples generally desire fewer children than they are currently giving birth to.

This has undoubtedly happened due to the declining prevalence of contraception, say experts. The use of contraceptives has fallen from 56 per cent to 53 per cent in a decade to 2015-16, according to National Family Health Survey-4.

On a positive note, the prevalence is rising among youngsters. In the 15-19 age bracket, it has improved from 14.1 per cent to 17.6 per cent over the same period.

Moreover, research suggests that the decline in fertility rates could partially be the result of increased abortions. In 2015, about 15.6 million abortions were conducted in India.

Unmet need for family planning

Currently, about 13 per cent of women in India want to space their children, or stop giving birth, but cannot do so. In absolute figures, the number of women of reproductive age who are unable to access contraceptives is a staggering 30 million.

A lot of it has to do with negligible male participation in family planning, says Sweta Das, joint director, family planning at the PFI.

“Male contraception has lost sheen due to the entrenchment of false notions, such as loss of masculinity and sexual appetite,” she said.

Dr Ranu Singh, incharge of reproductive and child health at the Patna Medical College and Hospital (PMCH), recounts similar experiences. She says that there has been no improvement in male involvement in family planning.

“Most men that we encounter think that family planning is a woman’s responsibility. They think that they will get physically weaker, and it will impact the family’s income. None of this is true,” she said.

As a result, about five per cent of births in India were unwanted at the time of conception, and about four per cent were mistimed or wanted at a later date, according to analysis of NFHS data by PFI.

Need for better adaptation to advanced methods

Two latest contraceptives for women, the injectable Antara, which works for three months and the pill Chhaya, which works for a week, have been inducted in the public health system in 2018.

“While injectables and implants entered the market long back, they came into government health services only six months ago,” said Singh of PMCH.

Family planning practitioners opine that injectables have a better impact, yet their introduction in government hospitals came at a much later date. This is especially significant when one considers that their prevalence in neighbouring countries is quite remarkable: 27 per cent in Nepal, 23 per cent in Bangladesh, and 29 per cent in Sri Lanka. Since the concept was introduced in India six months ago, there isn't any data available on its use.

Apart from injectables, implants have also made their way to the market. "There are hormonal implants used successfully in many countries. They are effective for three to five years and can provide ideal spacing between births. However, they are not available in India, not even in the private sector,” says Das.

Experts also noted that curative methods are becoming increasingly prevalent in actual practice. Post-abortion contraceptives are required in quantities more than before, but are unable to match the rate of increase in birth terminations.

This is riddled with inefficiencies. Due to the legal hassles surrounding abortions, about three million operations out of five million are unsafe in India, says Singh. In about 700,000 cases, some complication or the other occurs, resulting in 3,600 reported deaths.

Population momentum on the rise; focus on contraception should, too

All this only indicates that awareness and education on contraception should start not at the point at which pregnancy occurs, but at a time when individuals reach the age at which sexual activity starts.

The census of 2011 showed that the population bulge in India was present in the 10-14 age group, meaning the population in that age bracket was the highest among all five year age brackets.

Come 2018, the population bulge at the national level has shifted to the 17-21 age bracket. Now that's a group that isn't just approaching the reproductive age, but a larger sphere called sexual activity.

So even if the fertility rates have reduced, the number of people in the age group has peaked, which suggests that India might witness a sudden spurt in births in the immediate years.

“The only way to slow down the momentum is to delay age at marriage, delay the first pregnancy and ensure spacing between births,” the PFI says in a note.

The example of Bihar can be construed as a fallout of this. Bucking the ongoing trend of reducing birth and fertility rates, the birth rate in Bihar actually rose between 2015 and 2016 from 28.3 to 28.6. Bihar, in fact, was the only state to register a higher birth rate. Its fertility rate too increased from 3.2 to 3.3, official data shows.

Spacing, the best solution

Of 100 live births in India in 2016, some 22 births were for the third or subsequent child, according to data from the Sample Registration System. The figure varies from 7.6 in Andhra Pradesh to 39 in Bihar.

The prevalence of three or more children would reduce once spacing methods become the focus of family planning, experts said.

Just about four per cent of the money meant for family welfare goes into family planning. And of this four per cent, only three to four per cent is spent on contraception using spacing methods.

“There is a popular misconception among couples that using intra-uterine devices causes cancer, makes a woman permanently infertile and causes headaches. All of this is untrue,” says Ranu Singh.

Bihar has the highest fertility rates among big states in India. But at the micro level, Ranu Singh's team at Patna's PMCH has improved the usage of IUDs in the hospital to three per cent, which is twice the national average of 1.5 per cent.

However, as far as the adoption of new contraceptives is concerned, Singh says that its impact cannot be ascertained yet.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)