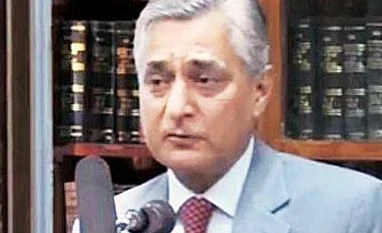

Justice Tirath Singh Thakur, who will take over the chief justiceship from Justice H L Dattu on December 2, has an unenviable task ahead in the coming months. The government and the judiciary are sparring over the method of appointment of judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts.

The Constitution Bench is currently hearing suggestions on making the collegium system more transparent and acceptable to the public. Owing to this crisis in relationship, some 400 vacancies have arisen in the 24 high courts. Justice Thakur has to watch how the constitution Bench proposes to relaunch the collegium. The number two in the judicial hierarchy, Justice J S Khehar, observed on Tuesday that being a Supreme Court judge is "killing" and the work burns him out.

But Justice Thakur is not the one who faces such a danger. He is cool and generous and spices the hearing with bits of humour. Last week, he delayed his lunch for half-an-hour to hear a woman lawyer who wanted a ban on Sardarji jokes on websites. His comments evoked laughter in the courtroom. He has a gentle voice, and he is the first judge in three decades who switched on the sound system. So the public and the mediapersons need not stretch their ears to hear what falls from the judge.

One of his recent notable judgments is in a public interest petition in which he passed a series of orders directing states which have not set up human rights commissions to do so within six months. All vacancies for the post of Chairperson or members will be filled up in three months.

Justice Thakur has handed down several judgments coloured by his sense of equity and fairness. He is known to dump technicalities of law when justice has to be delivered. He quashed the trial of a bill collector of a Karnataka village panchayat who allegedly took a bribe of Rs 500 in 1998 (Nanjappa v State of Karnataka). Ending the debilitating trial, he wrote: "We do not see any compelling reason for directing a fresh trial at this distant point of time in a case of this nature involving a bribe of Rs 500, for which he has already suffered the ignominy of a trial, conviction and a jail term." When he was the Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, he steeply hiked the compensation for the kin of victims of the disastrous Dabwali fire incident. He also increased the liability of the Haryana government for its negligence. Thakur has seen judiciary and government at close quarters, as he was the son of a noted lawyer, D D Thakur, who became deputy chief minister of Jammu & Kashmir and later governor of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Now, it is his turn to show statesmanship by steering judiciary harmoniously with a government which feels deeply hurt by the recent judgment in the judicial appointments case.

With a term ending in January 2017, he has to move fast to tackle the tough tasks cut out for him. Arrears in the Supreme Court have mounted to around 65,000. There are some 30 million cases in various courts. Budget allocation for judiciary is a miserly 0.2 per cent of the gross domestic product. The judge-population ratio is 10.5 to one million, which should be 50 to one million. These are only some of the chronic problems the judiciary has not been able to solve. If Thakur can carry the situation by one step further, his contribution to the judiciary in these troubled times would be memorable.

The Constitution Bench is currently hearing suggestions on making the collegium system more transparent and acceptable to the public. Owing to this crisis in relationship, some 400 vacancies have arisen in the 24 high courts. Justice Thakur has to watch how the constitution Bench proposes to relaunch the collegium. The number two in the judicial hierarchy, Justice J S Khehar, observed on Tuesday that being a Supreme Court judge is "killing" and the work burns him out.

But Justice Thakur is not the one who faces such a danger. He is cool and generous and spices the hearing with bits of humour. Last week, he delayed his lunch for half-an-hour to hear a woman lawyer who wanted a ban on Sardarji jokes on websites. His comments evoked laughter in the courtroom. He has a gentle voice, and he is the first judge in three decades who switched on the sound system. So the public and the mediapersons need not stretch their ears to hear what falls from the judge.

More From This Section

Though he has heard high-profile cases such as the Board of Control for Cricket in India shenanigans and the never-ending moves to release Sahara boss Subrata Roy from Tihar jail in Delhi, his patience and meticulous approach have disarmed the array of senior counsel on both sides. He deals mainly with criminal matters and has before him the various chit fund scams, like Saradha from West Bengal. He had a brush with Vyapam scam before it went before Dattu.

One of his recent notable judgments is in a public interest petition in which he passed a series of orders directing states which have not set up human rights commissions to do so within six months. All vacancies for the post of Chairperson or members will be filled up in three months.

Justice Thakur has handed down several judgments coloured by his sense of equity and fairness. He is known to dump technicalities of law when justice has to be delivered. He quashed the trial of a bill collector of a Karnataka village panchayat who allegedly took a bribe of Rs 500 in 1998 (Nanjappa v State of Karnataka). Ending the debilitating trial, he wrote: "We do not see any compelling reason for directing a fresh trial at this distant point of time in a case of this nature involving a bribe of Rs 500, for which he has already suffered the ignominy of a trial, conviction and a jail term." When he was the Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, he steeply hiked the compensation for the kin of victims of the disastrous Dabwali fire incident. He also increased the liability of the Haryana government for its negligence. Thakur has seen judiciary and government at close quarters, as he was the son of a noted lawyer, D D Thakur, who became deputy chief minister of Jammu & Kashmir and later governor of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Now, it is his turn to show statesmanship by steering judiciary harmoniously with a government which feels deeply hurt by the recent judgment in the judicial appointments case.

With a term ending in January 2017, he has to move fast to tackle the tough tasks cut out for him. Arrears in the Supreme Court have mounted to around 65,000. There are some 30 million cases in various courts. Budget allocation for judiciary is a miserly 0.2 per cent of the gross domestic product. The judge-population ratio is 10.5 to one million, which should be 50 to one million. These are only some of the chronic problems the judiciary has not been able to solve. If Thakur can carry the situation by one step further, his contribution to the judiciary in these troubled times would be memorable.

)