Permit me to begin with a confession. I am an Assamese who grew up with an aversion for people from Bangladesh. In my defence: It was a widespread sentiment, especially in the Eighties which witnessed the Assam Movement, a six-year popular agitation seeking to rid the state of “foreigners”.

The movement ended in 1985 with the signing of the Assam Accord between the state leadership and the Union government. One of the promises made under the accord was the updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which was first prepared in Assam in 1951. The final list of the updated NRC, which bases March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date for registration, was released in Guwahati last week.

In Assam, there has been speculation for decades over the number of immigrants, predominantly Muslim, entering the state from erstwhile East Pakistan or Bangladesh. Growing up, my understanding was that they were poor, lived in ghettos and migrated to Assam in large numbers in search of land and jobs.

I spent a few childhood years in North Lakhimpur, a town in northeast Assam bordering Arunachal Pradesh. There was a settlement of people of eastern Bengali descent near our government quarters. Some of the women worked as domestic help. An elderly man with a flowing white beard used to come to our doorstep to sell fish. As we were leaving for a different town, he smiled, “You are abandoning us.” His expression was odd, both teasing and bereft.

In Lakhimpur, more than the community we suspected were “outsiders” it was in the presence of another category of individuals that our identities and differences were thrown into sharp relief. Not individuals, precisely, but an institution: the army.

One afternoon, I was at the home of Islam borta (Assamese for father’s older brother), my father’s senior colleague. The house was next to an elevated stretch of NH-15, which crossed the Subansiri river a few miles away. I went up the slope from the front yard to the bamboo fence to fetch a cricket ball, quite close to the vehicles that sped past on the highway. I saw a jawan gesturing to the driver of a truck to pull up. Not a word was exchanged, and the jawan slapped the driver the next moment. I ran back inside, experiencing mortal fear for the first time.

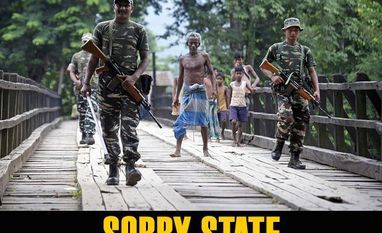

Instances of youths being picked up weren’t unheard of, and we learned to internalise a familiar fear. The Union government had launched Operation Bajrang to pursue separatist militant groups such as the United Liberation Front of Assam and the National Democratic Front of Boroland. I felt a sense of comfortable security that the jawans at the check posts had no questions for my father when he showed them his state government-issued identity card.

As I moved to Delhi to attend college and stayed on when I got a job, the realisation that I was now a migrant too aroused in me empathy with the Bangladeshi immigrant in Assam. Migration, I began to understand from this distance, was a universal phenomenon. For most Assamese living in Assam, though, it is hard to see beyond the bottomline: that an economically backward state cannot absorb a swelling migrant population and provide adequate job opportunities for all, apart from preserving its traditional cultural identity with changed demographics in the long run.

As the NRC update issued its final list, the exclusion of 19 lakh people – roughly six per cent of Assam’s population of 3.29 crore – was met with varying degrees of dissatisfaction across the board, and for varying reasons. The All Assam Students’ Union and the Asom Gana Parishad – both signatories to the Assam Accord – said that the number of persons excluded was far lower than expected. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) expressed its unhappiness through state minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s alleging manipulation of data and demanding re-verification. The All Assam Minority Students Union raised apprehensions that the NRC may have included names of Bangladeshi immigrants and excluded Indian citizens. Each person whose name doesn't figure in the final NRC list will have a maximum of 120 days to challenge his or her case at a foreigners’ tribunal.

A bureaucratic process that can strip citizenship from a sitting legislator, the family of a former President of India or a retired army officer can only be seen as greatly flawed, especially in a country where official documentation is poor. Despite its flaws though, the allegation that the exercise was skewed in favour of Hindus and was anti-Muslim – as has been alleged by many – does not seem borne out. A large number of Bengali Hindus are reported to be on the list.

Assamese scholar Hiren Gohain, who had criticised the 80s’ movement as being driven by chauvinism, has defended the NRC. The results should “set at rest the tireless campaign by certain well-meaning but ill-informed people in the academic and media circles to paint the NRC as a vicious plot by some ‘xenophobic Assamese’ to oppress and torture Muslims”, he wrote in The Hindu.

If a resolution to the long-standing question of “Who is Assamese?” is seen as the only path forward in the state, perhaps the solutions lie in an understanding of the past.

After it was annexed by the British, Assam was made a part of the Bengal Presidency. Sanjib Baruah, professor of political science at Bard College in New York, in an interview published in the Asia Society website, notes that the British saw the empty lands of Assam as a solution to the problems of land-scarce Bengal. Between 1905 and 1912, the British created a new province called East Bengal and Assam with Dacca as the capital. “Before 1874, Assam was ruled as part of Bengal and, until 1873, Bengali was the language of the courts and government schools in Assam,” Baruah says.

Assam has a sizeable Bengali population, concentrated mainly in the Barak Valley. Given the history, “differentiation from Bengal and Bengali culture has been a major theme in Assamese identity politics – which has made Assamese-Bengali relations sometimes conflict-prone”, he adds.

The relatively small numbers (be it Assamese, Manipuris, Nagas or Mizos) for different local populations of the Northeast vis-à-vis the densely populated subcontinent has worked against them. Baruah, who has advocated decentralisation in his book India against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality, points out that Northeasterners have to approach Delhi or plead with the Indian media because decisions are made there.

One way of viewing the sub-national conflict in Assam is by reasoning that a region like the Northeast experienced an incomplete process of modernisation, that it was subsumed into the Indian state before it could form a modern society of its own and without being accepted as an equal stakeholder subsequently. However, Baruah has located such conflicts in the inherent contradictions within the nation state. “We have all got used to seeing nation states as the most ‘normal’ way of ordering the world… But making nations has actually been a very bloody process, not just in the ‘third world’...,” he says.

Historically, the colonial inner line which became the basis for separating the hills from the plains in the Northeast has had “an unintended beneficial consequence”. Compared to states such as Assam and Tripura, Baruah points out, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Mizoram have been protected from a large-scale influx of population.

The Assam Accord provided for the “detection, deletion and deportation of illegal foreigners from the state”, and the promise of deportation has also been made by the ruling BJP. However, this doesn't appear to be an option. India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar said recently in Dhaka that the ongoing process to enumerate citizens and non-citizens in Assam was India’s internal matter, while Bangladesh’s Foreign Minister Abul Kalam Abdul Momen said he didn’t think those excluded from the NRC were Bangladeshis and that his country was “already in serious trouble with 1.1 million Rohingyas”.

Several commentators, including journalist Sanjoy Hazarika, have suggested issuing work permits to those who have not been recognised as citizens. He has proposed that work permits be issued to groups of workers who can be denied political and voting rights or the right to own property and settle in India, but who would have human rights and could approach the courts and labour commissions.

A proposal of this nature is likely to lead to many more debates and may struggle to find consensus. Meanwhile, there are already alarming signs of what awaits those who become stateless. Work has begun to build a detention centre in Goalpara district at a cost of Rs 45 crore and with a capacity to hold 3,000 detainees. Eleven such centres are being planned across the state.

Assam has six detention centres that are run out of district jails. Activist Harsh Mander, who visited two such centres last year as special monitor for the National Human Rights Commission, wrote in Scroll that “these detention centres lie on the dark side of both legality and humanitarian principles” and that the inmates are “treated in some ways as convicted prisoners, and in other ways deprived even of the rights of prisoners”.

The BJP is likely to reintroduce and pass the Citizenship Amendment Bill, 2016, which aims to change the definition of illegal migrants. It seeks to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955, to provide citizenship to illegal migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, who are of Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian faiths. Prior to the general election this year, there were widespread protests in the Northeast against the proposed Bill. If the BJP goes ahead with its promise, it bodes ill for India's claims of being a secular democracy, and it will also render the NRC update somewhat redundant by according citizenship status to all excluded “foreigners” except for Muslims.

If there was a sense earlier that the Northeast, including Assam, saw ethnic fissures and little development with previous governments at the Centre, there is now enough indication of the current dispensation attempting to communalise a crisis that is not religious but economic and political. As Assam looks ahead after a bureaucratic exercise that cost the country Rs 1,200 crore, is it not the responsibility of the Centre, which is guilty of viewing the Northeast as the Other, to rehabilitate those excluded from the NRC in a way that restores their human dignity? That, with a serious effort to help Assam's diverse ethnicities overcome old prejudices, may offer a sense of closure, a resolution of conflicted feelings for all of us.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)