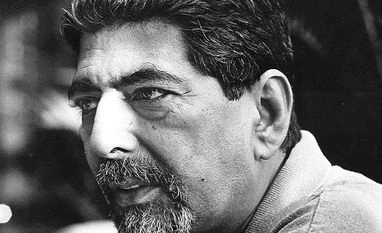

Sonny Mehta, the India-born, Cambridge-educated editor who for more than 30 years presided over Alfred A Knopf and the New York publishing scene with seemingly effortless grace and erudition, died on Monday at 77. Mehta published Nobelists and Pulitzer Prize winners as well as first-time authors, and here he is remembered by some of the writers whose careers he shaped.

John Banville

I loved Sonny for his grace, his insouciance and his sly, quiet humour. When he first told me of the mysterious, debilitating illness that attacked him some years ago, he described how one day he found himself fallen onto the pavement on Central Park South and unable, for the moment, to get up again. Naturally, people just stepped over him — Manhattanites always have somewhere very important to go to — but then a pretty young woman stopped, as pretty young women will, and knelt beside him and asked what she could do to help. Sonny, relating this to me, did one of his wistful smiles, and said, “You know, she really was very pretty.” Of course, soon his wife, Gita, urgently summoned, arrived to rescue him.

He loved the world and his loved ones, and was a great champion of good books in particular and of humane culture in general. The death of every noble man makes a slight, ignoble adjustment to the world. He would have wished us better times ahead. I shall miss him to the end.

Omar El Akkad

They used to warn you, before you first met Sonny Mehta, not to be intimidated by the silence. Don’t let it throw you off, my agent told me, he just doesn’t say much.

Truth is, he didn’t have to. The best writing advice I’ve ever received came delivered from him in single sentences — simple yet deeply nuanced advice I would think about for months, each time arriving at the realisation that what he suggested was exactly what the work needed. His gift, I think, was to read every manuscript twice at the same time — once for exactly what it was and once for everything it could be.

I’m not sure my friends outside the writing world believed me when I told them I had the finest editor in the world. But I did. More than anything I have achieved or ever will achieve, those rare afternoons spent in Sonny’s office listening to him dissect the inner workings of a novel will always be the fondest memories of my career. He came to literature from a place of love, and that love is evident in every book he ever touched.

Bret Easton Ellis

I often felt intimidated by him. I first met him in 1986, when I was 21 and had been flown to England and was being introduced to the UK publishing world; Sonny had just published my first novel, Less Than Zero. The second night I was in London, I was at Sonny and Gita’s home. Sonny was very solicitous, to the point of asking the young American writer where he’d like to have dinner that night — we were with a group — and I suggested “sushi?” not really grasping the culinary limitations of London in the mid-1980s, expecting that Japanese restaurants and sushi bars were as popular there as they were in Los Angeles. I remember a distinct hesitation fell over the living room as we finished our drinks, and then Sonny waved it off and spent the next 45 minutes not only locating a Japanese restaurant that served sushi but one that was open and could accommodate a party of six. An hour later, we were seated in a somewhat deserted Japanese restaurant far from Sonny’s house. I was mortified that I had caused this complication, and I remember telling Sonny: “Really, you did not need to do this.” “Please,” he said as he lit a cigarette, “you’re the writer. The writer always comes first.”

Joseph J Ellis

When I somewhat surprisingly won the National Book Award in 1997, Sonny and his lovely wife, Gita, were seated at my table. He leapt up, tried to stand on the chair while cheering, then gave me a push to go up to the stage and accept the award. No one was more visibly happy for me than Sonny.

Carl Hiaasen

Sonny was my editor for the last 29 years, and a dear friend. He was always the most interesting person in the room — and yet the quietest. The first time I went to meet him, I was completely intimidated. I got to his office at 10 in the morning, and there was a bottle of Scotch already open on his desk. I thought, “This is going to work out fine.”

I remember when I was finishing one of my novels he announced he was coming to South Beach to do the final edit face to face, which wasn’t our typical routine. I was worried that he didn’t like the final draft and wanted to tell me in person.

When I arrived at his hotel, I found the manuscript in neat little stacks all over Sonny’s room. We spent less than an hour going over his notes, and the rest of the night we hung out on Ocean Drive, eating and drinking. It was winter, and basically Sonny just wanted a fun trip to Florida. Looking back, I wish we’d done it that way on every novel.

Richard Russo

Many years ago, when I was in London to promote one of my early novels, Sonny Mehta somehow found out that I was in town and invited me for a drink at his flat in Knightsbridge. He also invited an Iranian novelist he wanted me to meet. The invitation was especially generous given that, if memory serves, I was then published in hardcover by Random House, though Vintage, Sonny’s imprint, published me in trade paperback. He and I had met maybe once or twice before in New York. But of course he’d read my early books and no doubt surmised from these that I was a small-town boy who would be feeling a bit out of his depth in London (I was), and that with this invitation he would make me feel both welcome and important. Anyway, at the end of a very pleasant evening we decided to go out for a bite to eat. It was raining, though, and the restaurant was a bit too far to walk to, so a taxi was in order. Outside Sonny’s flat, the Iranian novelist said, “We’ll probably have more luck if we let Richard hail it.” My first reaction was puzzlement. Why would someone like me, who hadn’t a wealth of experience hailing big-city taxis, be more likely to succeed than my two urbanite companions? But before I’d even fully articulated the question, I understood. I had light skin. I remember glancing at Sonny, whose sad expression seemed to say, “He’s right, you know.” Even now I can feel the profound embarrassment of acknowledging this shared truth about the world we lived in, and the look on Sonny’s face suggested that he, no doubt a regular victim of that same world, was also deeply embarrassed.

In fact, I think that’s what I’ll remember most about Sonny, the impression he so often managed to convey: not just that the world needed to be a kinder, fairer, better place than it was, but also that he might somehow be partly to blame, that he’d been aware of the world’s imperfections for some time now and meaning to do something about them, but it had somehow slipped his mind and so, as a result, here we were with no choice but to genuflect before its ugliness. In a world where far too many people refuse to take responsibility even for what is clearly their fault, here was a man who felt responsible when he wasn’t. A man, in other words, whose moral imagination could be counted on. The kind of man you’d be pleased to give your book to when you yourself couldn’t make it any better.

Jane Smiley

Sonny was always smart and kind and friendly. Maybe what I am most grateful for is that he let me do what I wanted to do. He championed The Greenlanders, which, I think, everyone thought was truly odd and maybe not sellable. I talked him into a few other things, too. But I think my best memory was just going to an Indian restaurant with him somewhere in Manhattan, and then strolling back down the street, chatting about this and that. I was very fond of him, and will miss him so!

Graham Swift

Sonny published me first in Britain in the 1980s, then in the United States. The reality was he gave me a personal bridge between London and New York. My very sense of New York, at least of Manhattan, is bound up with being in it with Sonny, with literally walking round it with him, block after block, sometimes for hours, slipping into this or that bar. He loved to walk. This made cruel the frailty in his legs (handled with impeccable dignity) in recent years. But right up until a few months ago he’d also wing into London and we’d meet. I felt he continued to watch over my British publications as much as the American ones, and I must be far from alone in feeling that the quality of watching over you was something he uniquely gave. To be watched over by Sonny and have his personal friendship — what a deal! No publisher was ever more closely at my side or ever made me more welcome in his own home — the London or New York one — as if it might be mine. He was a peerless champion at what he did and yet his great gift and mission was to champion you, to champion writers. To be championed by a champion for almost 40 years: that is something beyond price, an honour for which I can’t be too grateful. What an immense loss.

Edmund White

After my novel A Boy’s Own Story was turned down by my previous London publisher, Sonny bought it, surrendered his own office for interviews with every small gay bar publication, arranged for a sellout public event at a trendy theater, gave a chic party at his house, where his jet-set wife arrived after jumping out of a plane with Viscount Linley, the queen’s nephew, and where the beautiful whippet wore an expensive pearl necklace and half the guests were sniffing cocaine. He sold 100,000 copies, and the publicist, Jacqui Graham, won a prize. A heady moment for a simple guy like me from the Midwest.

@ 2020 The New York Times

SALMAN RUSHDIE

I first met Sonny in London in 1982 when he was at Picador, in Britain, and about to publish the paperback of Midnight’s Children. I arrived at his office, and after he said hello, he handed me a copy of Ryszard Kapuscinski’s book about Haile Selassie, The Emperor. “You have to read this,” he said. “It’s the best book I’m publishing this year.” Humility was the first lesson he taught me.

In 1986, I visited Nicaragua and wrote a first draft of a reportage book about the Sandinistas and the Contra war, which Sonny, in Britain, and Elisabeth Sifton (another sad loss this year), in the United States, would publish as The Jaguar Smile. This was when I learned how great Sonny’s editorial skills were. We went through the draft line by line, and he asked questions, wanted clarifications, demanded more depth and improved the text beyond all measure. The book in its published form owes everything to him.

In 1990 we had a profound disagreement over my novel Haroun and the Sea of Stories, which strained our friendship for some time; but five years later he was the passionate publisher of The Moor’s Last Sigh and insisted on accompanying me everywhere on my United States book tour, and then everything was all right again.

He was on the phone a lot during that book tour, because he was also publishing a novel by Dean R Koontz at the time. “It’s doing very well,” he told me. “We just printed 400,000 hardcover copies.” Once again, his great support for my work was accompanied by a lesson in humility.

When he was honoured at the Center for Fiction gala last year, Sonny abandoned the taciturn habits of a lifetime and spoke at great length, and with deep emotion, about his life in books. All of us who heard him that day were greatly moved, partly because it was such a shock to hear him speak so openly — and so much! — and partly, I think, because we feared it was a sort of farewell. It’s so sad, today, to know that it was.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)