The unemployment rate in India declined to 4.8 per cent in the period July 2019 to June 2020, from 5.8 per cent in July- June 2018-19, latest data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) released by the National Statistical Office shows.

Labour force participation also rose during that period. As many as 53.5 per cent of people above 15 were working or looking for a job in the period July 2019 to June 2020, up from 50.2 per cent in the same period of 2018-19.

This is interesting--and counter-intuitive too—because it happened at the backdrop of two major disruptions: one, a severe economic slowdown which had its roots in demonetisation, and two, the massive shock of Covid-19 pandemic. About four months of the survey period coincided with the nationwide lockdown announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a bid to contain the spread of the pandemic.

But there are a few factors that explain how this happened, and some others, which show a rising unemployment rate.

The figures mentioned above capture the status of a person for the entire reference period, that is, July 2019 to June 2020. This is known as the “usual status” of a person’s activity, and a person is captured as employed if she or he was working for more than 30 days in this period.

There is another way in which employment is measured by the NSO, and that is using the “current weekly status.” CWS captures the status of a person in the latest week when the response was recorded.

According to the CWS method, the job situation did not improve, but deteriorated. Unemployment rate for those aged 15 years and above worsened to 8.8 per cent in 2019-20 from 8.7 per cent in 2018-19 (July-June).

Though the average unemployment rate has dipped only marginally, that for urban men declined sharply from 8.8 per cent in 2018-19 to 10.5 per cent in 2019-20.

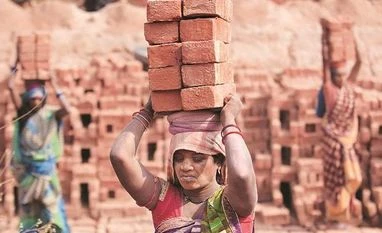

Interestingly, this was—if not fully, at least partially—balanced out by a sharply falling unemployment rate for rural women, from 7.3 per cent to 5.5 per cent.

In a way, rural women compensated for rising unemployment in urban men by entering the labour force with rigour, and in that, getting employed better.

From 22.5 per cent in 2018-19, as many as 28.3 per cent women were working or looking for work in 2019-20. As a result, the share of workers in women above 15 rose from 20.9 per cent to 26.7 per cent in that period, suggesting that a higher proportion of women who were looking for work, actually got work.

Eminent statistician P C Mohanan, who was formerly a member of the National Statistical Commission, said that two things could have made this possible: more jobs under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA), and more work as subsidiary status, than principal status.

The “usual status” is an ensemble of two statuses, principal status, meaning being involved in work for more than six months, and subsidiary status, or working for any time between 30 days and six months.

Even if more people are workers in subsidiary status, it would reflect as employed in usual status. It needs to be checked if that is the case, Mohanan said.

And then, the central government spent more than budgeted on the rural employment scheme to address the impact of the pandemic. This could have added to casual labour jobs in the last quarter of the reference period.

A falling unemployment rate using “usual status” and a marginally rising rate using CWS could have three other reasons, too.

Firstly, the unemployment rate using CWS increased sequentially: it was low in the first two quarters of the reference period (July-December 2019), marginally increased in the quarter ending in March 2020, and sharply in the quarter ending in June 2020.

The CWS method thus captured the growing precariousness more accurately. Many respondents in May 2020 may have got registered as “unemployed” for CWS as they would have lost their jobs due to lockdown, but would still have got registered as “employed” for “usual status” as they would have worked for more than 30 days in the year gone by.

Secondly, employment was gradually recovering from the economic shock of demonetisation already. A look at quarterly urban unemployment rates from PLFS shows that for men, it fell from 8.9 per cent in mid-2018 to 7.3 per cent towards the end of 2019.

Thirdly, the changes in the nature of employment could also be a factor. Agriculture and trade occupied a higher share in overall employment in 2019-20 compared to the previous reference period, while the share of manufacturing, construction, and other services declined.

The growth in women’s labour participation (as mentioned earlier) in rural areas could be a reason for this.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)