On September 6, the Supreme Court struck down the colonial-era Section 377, effectively decriminalising homosexual relationships. What followed was a series of celebrations across the country, from fashionable soirées to quieter dinners. Jaspreet Singh (name changed on request), a 24-year-old executive who works for a Mumbai-based financial services company, didn’t join any though. He was still preoccupied with concealing his sexuality from his co-workers. “I hear people making homophobic jokes all the time and I don’t think I’m ready to be out to my colleagues,” he says. When he is quizzed about a girlfriend, in classically Indian nosy style, he plays along and offers a vague answer.

In what seems like a parallel universe to Singh’s, not only is Aditya Shankar a proud member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community, he also heads a dedicated employee resource group at the company he works for. Shankar, a 25-year-old senior associate consultant at consulting firm Bain & Company in Mumbai, leads the Indian division of the Bain Gay and Lesbian Association for Diversity, or BGLAD, a diversity initiative that the company has instituted in its offices across the world. After the Supreme Court verdict, BGLAD was at the forefront of mobilising other multinationals. Bain then sent out a crisp statement supporting the verdict, which was jointly signed by Bridgespan.

Indian companies now have a unique employment dimension to address, in terms of eliminating prejudices as well as instituting policies that don’t exclude LGBTQ employees from the benefits that heterosexual employees enjoy. Some, like The Lalit Suri Hospitality Group, Godrej, Tata and Infosys, have been making strides to broaden the definition of inclusivity. Others, including global companies like Bain & Company, KPMG, Accenture and Adobe, have been able to replicate their diverse workplaces across the world in India through various forums, support groups and gender seminars.

But for a large majority of home-grown start-ups and small and medium enterprises, the issue of a gender-diverse and equal workplace is not even a blip on the radar. Traditional workplaces, many still struggling to offer adequate maternity leave and basic amenities to their female employees, are not yet equipped to fully acknowledge the wide spectrum of diversity.

Insurance is the most obvious employee benefit that begs consideration. For life, accidental and health insurance covers, only spouses, family members and legal heirs can be nominated to receive benefits. Given that India’s legal scenario still does not recognise same-sex domestic partnerships, this is a tricky situation. Insurance policies generally use the word “spouse”, which indicates a legally valid marriage.

“At the moment, I can only claim medical expenses for my ‘wife’ or my parents. I can’t even nominate my partner in my bank account,” says Siddharth Gurnani, a 34-year-old executive based in Bengaluru. “What if someone’s parents are no more? I would want this money to go to my partner and not languish in the account.”

Though the provident fund and the insurance and banking sectors are regulated by the government, it isn’t as if private companies cannot find a workaround to this. Companies like Godrej have changed the terminology from “spouse” or the “husband/wife” binary to simply “partner”. Hospitality start-up OYO Rooms, too, has a group insurance policy arrangement that covers the “significant other”, which includes same-sex partners too, according to Dinesh Ramamurthi, chief human resources officer at OYO.

Most companies use a foreign helping hand — they buy insurance policies for LGBTQ employees from global insurance providers that recognise same-sex domestic partnerships and civil unions. But some organisations have been able to negotiate terms with Indian insurance providers, too. The Lalit is one such case. “Our group mediclaim policy has been crafted to include the families of LGBTQ employees, their adopted children or those born through surrogacy to heterosexuals, same-sex couples and single parents,” explains Keshav Suri, executive director of The Lalit Suri Hospitality Group and a gay rights activist. In The Lalit’s case, ICICI Lombard made appropriate additions to the health insurance cover for the group.

Commonly, companies with more woke policies are those who have on their rolls employees who have been able to speak up for their rights or senior executives who belong to the community. “Policies or workplaces are not necessarily homophobic, but they are certainly oblivious,” says Bain’s Shankar. “It boils down to how employees alert their organisations to the needs of the LGBTQ community.”

But even diversity through the prism of insurance policies and benefits can be restricted to gay and lesbian people, and entirely neglect the rights and needs of transgenders. Sumit Kumar, a diversity and inclusion expert, believes that health cover must also include expenses for gender reassignment surgeries, tests, counselling and hormone therapy. “Sometimes, basic things like gender-neutral washrooms can go a long way in making queer employees feel safe and more confident in their identity,” says Kumar.

The issue of safety, too, is a key aspect that is often ignored. “The prevention of sexual harassment (POSH) policies in most of the companies still cover only harassment against women. Other forms of harassment are treated as employee grievances,” says Rashmi Vikram, senior manager for diversity and inclusion, Diversity & Inclusion in Asia Network for India (DIAN), which is a part of Community Business, an organisation that aids and trains companies to adapt themselves to become more inclusive. OYO, for instance, has made some progress in this direction. “Our POSH committee is now well trained to address issues involving either gender and now cases involving the same gender,” says Ramamurthi.

“Organisations can start by relooking at their policies and make them gender-neutral. They also need to ensure that their policy wording is expanded to include the LGBTQ community, too,” says Vikram. For instance, employee benefits sometimes also include travel with spouse, study leave or leave allowance for marriage. “Companies can start by including leave allowances for transitioning individuals, too,” says Kumar. Beyond adding neutral washrooms, human resources professionals must also, according to Kumar, pay attention to onboarding forms and identity documents. “Transpeople often struggle with documentation during or after transitioning. This could even impact an executive’s hotel stay if her identity proof categorises her as male,” says Kumar.

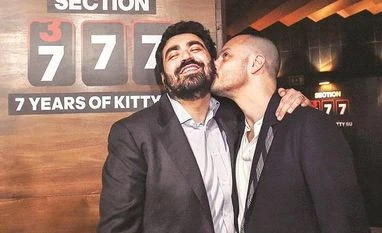

An enabling environment for a truly diverse workplace will really arise only once a company puts in place a diversity-focused hiring policy. The Lalit, for example, has been able to employ 10 transpeople across its various hotels and at different levels of seniority. The Lalit Delhi’s club, Kitty Su, has had performances by drag queens and transpeople to give them a more mainstream audience. For Suri, sensitisation is a round-the-clock job. “Employees will not give 100 per cent of themselves if they can’t come to work being themselves,” he says. The BGLAD initiative, for instance, has proven to be so enabling that an employee felt confident enough to come out in front of his colleagues at a Bain offsite that coincided with the Section 377 verdict.

But Suri is an outlier in the Indian corporate world. DIAN’s Vikram believes that mentoring within the community is a huge void that holds back LGBTQ representation in offices. “There are few open LGBTQ leaders in Indian organisations and, though this number is now growing, it is still slow. The out executives are important in terms of sending a clear message to more junior LGBTQ employees (who may still be concealing their identity), that it is all right to be open about one’s sexual orientation or gender identity,” she says. In such a scenario, a strategic practice for hiring senior LGBTQ professionals is necessary. “Many companies in India still do not understand the business imperatives behind having an LGBTQ-friendly or inclusive environment. They still associate this with the idea of sympathy or ticking some social responsibility box,” she adds.

While DIAN and the Naz Foundation are now working with organisations and conducting gender-sensitisation seminars, most workplaces still have miles to go. “A lot of the associates still remain tight-lipped about their identity, especially because of the casual sexism and jokes,” says Gurnani. Shankar, from Bain’s BGLAD, says that this can only be helped if people are made more aware and told off. “Sometimes, people have been called out and publicly shamed for their nasty jokes. We take this quite seriously,” he says.

But Singh, far away from this progressive universe, is still wondering if he’ll ever be able to take his partner as a plus-one to an office party. “Homophobia is not latent, it’s quite blatant. The verdict is way ahead of its time because, in reality, we are still quite backward. For now I just hope my colleagues can realise that their words hurt me.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)