The protests by Ram Rahim’s followers resulted in the deaths of at least 38 people in Haryana, where the court held its proceedings. Many more were injured, and widescale damage to public property has been reported.

This defence of a rapist spiritual guru is quite unexpected in a country that’s been home to intense gender activism and public outrage on the issue of violence against women in recent years.

So, who is this “godman”? And what is Dera Sacha Sauda, the religious cult he heads in northern India, which has drawn into its fold thousands of followers ready to sacrifice their lives for their guru?

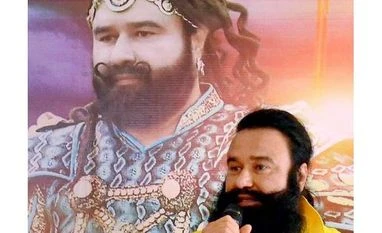

Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, the ‘guru of bling’

Ram Rahim is known as a “baba” or “guru of bling”. Referred to as pitaji or revered father, he has lived in a sprawling compound, enjoying highest-level security provided by the government to very high profile people.

Ram Rahim has had an extraordinary life filled with many idiosyncrasies. He is definitely not the average guru: he rode expensive motorbikes with his gang of followers; produced, directed and acted in his own movies; and performed in his own rock concerts wearing bizarre costumes. He also has an honorary doctorate from the University of World Records, London.

Unlike his contemporary gurus who are seen as spiritual guiding lights, Ram Rahim is treated as an avatar of the almighty himself. He considers himself as the “Messenger of God”, and not just a person of higher consciousness who shows other people the righteous path.

The film he made and acted in, Messenger of God, was released in 2015. In the past, he also dressed up as a Hindu god and a Sikh guru, angering the followers of both religions.

His following includes many women who believe in his miraculous powers and all-embracing godly spirit.

The rape of two female followers was not the only accusation against Ram Rahim. He has been charged with murder and the castration of at least 400 men to “bring them closer to God”.

What is Dera Sacha Sauda?

Ram Rahim is the congregation leader of Dera Sacha Sauda (meaning “abode of fair deal”), a religious cult established in 1948. Its main centre is situated in the city of Sirsa in the state of Haryana, northern India.

The cult has 50 ashrams across India and branches in countries such as the US, Canada, UAE, Australia and the UK.

Its website declares it is a confluence of all religions advocating a complete ban on the consumption of meat, egg or gelatin in food and intoxicants such as alcohol, drugs and tobacco, and “no adultery or illicit sex”.

The group has had two leaders before Ram Rahim, each of whom chose their own successors, declared as their self-avatars.

With Ram Rahim jailed and no anointed heir, combined with the hefty fines imposed on Dera Sacha Sauda for the destruction of public property and arson, the cult’s future looks bleak.

The free market of spirituality

This episode has several important questions, mostly related to the crisis of spirituality and modernity in India today.

Religious and cult gurus in India are celebrities who have a tremendous impact on spiritual matters and on the lives of their followers. Their close association with politicians allows them access to political power and wealth. They can belong to any religion or sect.

The liberalisation of the 1990s in particular made spirituality a market enterprise: the gurus’ services could be purchased, and gurus indulged in profit-making activities.

That supposedly religious gurus could be involved in fraud, political manipulation, and sexual assault is not new in India. And yet the baba business flourishes.

For the poor, spiritual pathways and cult membership empowers them as they look for hope and miracles to survive the onslaught of neoliberalism. These spiritual pathways promise equality to the millions who feel discriminated, oppressed and marginalised.

The middle classes, however, can experience an existential crisis – and belonging to a religious or spiritual cult gives them purpose and meaning in life. The gurus have instant answers to all their problems.

The rich and powerful are also part of these cults, and they hobnob with the gurus. They have a lot to gain by following those who society follows – not just to tackle their insecurities but to cultivate a network of supporters who will always remain loyal to them.

The gurus can sway elections, generate funding for welfare projects, and provide hundreds of volunteers at a short notice.

The crisis of spirituality and the everyday dependence on miracles is only part of the problem. India’s political economy remains conducive for spiritual gurus to thrive and cultivate their loyal fan followings.

The recent episode has exposed the authorities’ vulnerabilities in dealing with unruly spiritual-seekers who have no qualms in defending their rapist gurus. After all, the guru is God – and God does no wrong.

Swati Parashar, Senior Lecturer, School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

One subscription. Two world-class reads.

Already subscribed? Log in

Subscribe to read the full story →

Smart Quarterly

₹900

3 Months

₹300/Month

Smart Essential

₹2,700

1 Year

₹225/Month

Super Saver

₹3,900

2 Years

₹162/Month

Renews automatically, cancel anytime

Here’s what’s included in our digital subscription plans

Access to Exclusive Premium Stories Online

Over 30 behind the paywall stories daily, handpicked by our editors for subscribers

Complimentary Access to The New York Times

News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter & The Athletic

Business Standard Epaper

Digital replica of our daily newspaper — with options to read, save, and share

Curated Newsletters

Insights on markets, finance, politics, tech, and more delivered to your inbox

Market Analysis & Investment Insights

In-depth market analysis & insights with access to The Smart Investor

Archives

Repository of articles and publications dating back to 1997

Ad-free Reading

Uninterrupted reading experience with no advertisements

Seamless Access Across All Devices

Access Business Standard across devices — mobile, tablet, or PC, via web or app

)