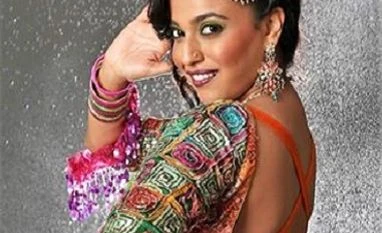

It’s 10:45 pm and Swara Bhaskar, 31, is exhausted but chatty. Her home on Mumbai’s Yari Road is a cosy place full of books, old film posters (I spot Cleopatra and Phagun) and three cats demanding her attention. The cool, confident young woman in ripped jeans and T-shirt looks so far removed from the rustic, flamboyant Anarkali of Aarah.

In the recently-released film, she plays a singer/dancer in a small town of Bihar, completely at ease with raunchy numbers. By day, she is another ordinary woman, shopping, making her tea or having the odd romp with her lover, Rangeela, who also manages the troupe. When the politically-connected vice-chancellor of the university molests her on stage, Anarkali slaps him. The ensuing battle between the two makes for an outstanding film and a comment on consent.

Bhaskar as the brassy, angry, talented and yet vulnerable Anarkali gives the performance of a lifetime in Avinash Das’s debut film, which released late in March to rave reviews. Every major filmmaker, from Imtiaz Ali to Anurag Kashyap, has applauded the film and Bhaskar’s performance.

Coming just a year after the heart-warming Nil Battey Sannata, it puts Bhaskar on the list of actors to watch out for — much like Nawazuddin Siddiqui after Kahaani in 2012. Ashwini Iyer-Tiwari’s Nil Battey Sannata, the story of a maid in Agra who is determined that her 15-year-old daughter will study and get out of the rut, won Bhaskar the best actress award at the Silk Road International Film Festival.

Add to this her other performances — Raanjhana (2013), Listen… Amaya (2013), Tanu Weds Manu (2011, 2015) or Prem Ratan Dhan Payo (2015) — and Bhaskar is already being talked of as the next Smita Patil or Shabana Azmi. Her choices reflect a new breed of actors not shy to try new things early on. So, there is It’s Not that Simple, a web series on Voot, and Shyam Benegal’s Samvidhaan, a show she hosted for Rajya Sabha TV.

How on earth did a Naval officer’s daughter with an MA in sociology from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) get into Anarkali’s skin? “My approach is sociological, anthropological; I do research and understand the space. I need to find a real-life reference,” says she.

Thus, for Anarkali, Bhaskar visited Aarah in Bihar more than once. She spent time with a singer called Munni and her troupe, went for performances by different singers, listened to their songs, interviewed and recorded them, made a list of the words they use and so on. This is when she comes alive jumping across the room to open her laptop and show me the videos she shot, the voices she heard.

‘I was always performing, always the dramebaaz, and always loved an audience. Acting is the only place I could have been satisfied and happy’

For Nil Battey Sannata she went to Agra, hung out with domestic helps, and got a sense of their world. Yet, she doesn’t believe in method acting. “If you are in films you need to preserve mind and body for the next role,” she says. “It is already an anxiety-generating stressful industry. That all of us are normal and sane is a big thing.”

But she always wanted to get into this world. Her father called her Isadora Duncan after the celebrated American dancer. “I was always performing, always the dramebaaz, and always loved an audience. Acting is the only place I could have been satisfied and happy,” she says. “When I was a child, my greatest desire was to be on Chitrahaar.”

Her mother, Ira Bhaskar, is a PhD in cinema studies from New York and teaches at JNU. Her father, C Uday Bhaskar, is a leading expert on security and strategic affairs. He was keen that she join the Indian Foreign Service. However, Bhaskar wanted “to do cinema, to come to Mumbai, to be Shah Rukh Khan”. She says: “I found it very seductive how close the camera comes to you.”

Thus, as soon as she finished her MA in 2009, Bhaskar landed in the city only to realise that “film is completely a director’s medium, you have no control, the longest take is 1-1.5 minutes and you don’t even know which take will make it to the final cut.”

The other big realisation was how looks-oriented the whole business was. “My great struggle was to look a certain way. I got my first film (which never got released) in three-and-a-half months, but I was told that I didn’t have the right attitude, that I looked too intelligent for a role,” she remembers. Even after Tanu Weds Manu was a hit, Bhaskar got no work.

Just when she was thinking of going back to Delhi, Raanjhana fell into her lap as the actress who was to play Dhanush’s friend walked out six days before the shoot. Raanjhana, thinks Bhaskar, was the turning point. After it succeeded, “I knew what to do.” She hired a PR manager and staff and set about professionalising her approach.

Her mother talked sense into her in this phase. “She told me that I couldn’t keep putting down the industry I was part of, and that I had to appreciate Bollywood for what it is, make peace with the way things are.” Has she? “I have become less judgemental. I came in with all my Leftist baggage, that stars are so dumb. But the fact is they are very smart.”

Working with Salman Khan in Prem Ratan Dhan Payo was an eye-opener. “Salman knows his craft, he is thinking of it all the time. And I have never seen an actor improvise the way he does,” Bhaskar says. “They all understand the craft and realise that the production needs to make money. I feel bad when my films don’t make money.”

Anarkali of Aarah may not have worked wonders at the box office, but films with women in the lead are beginning to become more viable than earlier. Vidya Balan, Kangana Ranaut and Deepika Padukone have quickly achieved what Madhuri Dixit or Sridevi took decades to do.

Yet, she feels, Bollywood is sexist. “Our society is feudal and sexist and, therefore, so is Bollywood,” says she. She points out that till corporatisation happened, Bollywood was more feudal, dynastic and star-driven. Those were the days when producers’ mortgaged their homes and cars for the films they made. It was their money at stake and, therefore, they had the right to choose actors et al. It has become less feudal after the coming of the studios.

But she feels there is no nepotism in Bollywood. “Look at all of us who are making it — Radhika Apte, Nawazuddin (Siddiqui), even Kangana — we are all outsiders.” But given the new breed of educated filmmakers such as Karan Johar and Avinash Das, it may seem elitist if you are not part of the English-speaking clique, she reckons.

Pay parity, however, is still a distant dream. “Equal pay for equal work won’t happen easily. If two actors of the same standing do 100 days’ work, the male one could be getting three times what the female actor gets,” says Bhaskar.

It bothers her but not as much as the box-office performance of Anarkali of Aarah. She talks about the exhibitor-distributor nexus and the trouble with getting a decent release for independent films. “We had to pay to screen the film, it is not enough to have a good film,” says she.

She has won the battle for acceptance — the one for a good release will take longer.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)