It’s the literature festival season and I am writing this from what is the prettiest venue for an Indian festival. I’ll come to that in a moment. But first, what explains the plethora of festivals in our parts?

It began with the Jaipur fest and, though it seems to have been with us forever, as a standalone festival, it has only existed since 2008, meaning a decade. Its success came upon it so quickly that it was established as an international venue for writers.

And then, following that lead, other festivals sprang up in its wake. Mumbai now has two, the Times Literary Carnival, run by Bachi Karkaria and Namita Devidayal, and Tata Literature Live, run by Anil Dharker. The former is held in Mehboob Studios in Bandra, one of the largest venues for such events anywhere in India. I last spoke there a few years ago in the main hall and there must have been some 2,000 or more people indoors. The latter is staged — I use the word deliberately — at Prithvi Theatre in Juhu. A cosy place with an amphitheatre. It also has its larger sessions across town at the National Centre for the Performing Arts at Nariman Point.

The festivals are interesting and different in their own way. The Carnival is run by the Times of India, which also has festivals in Delhi and Bengaluru. The one in Delhi, or at least the one I attended, was managed by Sagarika Ghose, the writer and journalist. It was in a unique location, the Oberoi Maidens. I say unique because it is a five-star hotel in a relatively old structure in a metro city. The Bengaluru one is often held at the Jayamahal Palace grounds, which is round the corner from my house and so I can just walk across to it. I am speaking there next month and I hope it’s in the same venue.

The 2018 edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival will see the participation of over 300 writers and poets

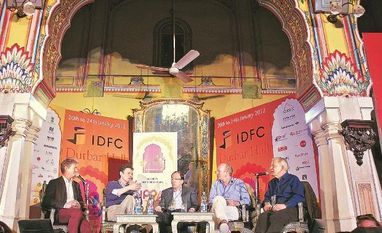

The place I am writing from, which I think is the most beautiful venue for such things, is the Kolkata Literary Meet (Kalam for short) organised by Malavika Banerjee. This is held at the Victoria Memorial, usually, and the audience has a full view of the stunning building behind the writers on stage. This year, the writers have an awning over their heads and that means the memorial is not fully visible when one is seated. Even so, the place is quite spectacular.

Another place that is visually striking is the Khushwant Singh Literary Festival, organised by Rahul Singh and Niloufer Bilimoria, and held inside the Kasauli Club. Indoors is not exciting but the outdoor venues are special, as is the audience which is comprised in large part of very formally (for India) dressed Sikh men and women of mature age.

Audiences vary marginally across the festivals and most seem to have a large number of young people, which is a good thing. In my experience, Jaipur has the largest in number, though perhaps not always.

So why do the authors and the organisers do what they do?

For authors, this is the rare occasion when they get to be heard and seen. Book readings are uncommon in our times. Even books sections have disappeared from most newspapers, meaning reviews and excerpts are no longer available serendipitously to lay readers. Means of publicity are few and publishers are unable to spend money promoting individual writers or books. This means that the author must do what she can and cadging and cajoling an invite to a festival, particularly a large one, is good publicity.

People who might not otherwise be interested will buy a book (and get it autographed by the author) and it’s influenced merely by the author’s presence.

Often, writers sell hundreds of copies in a few hours and I have seen this happen, though not for my book, of course.

Organisers do the festivals because... actually I don’t know why they do them. It seems hard work to me without much reward, though I could be missing something. Not a single festival here is ticketed and so all the money must come from sponsors. There is the travel sponsor (airline) and hospitality sponsor (hotel) but one still needs a lot of money. Where does it come from? Wherever it does I doubt it is much and I doubt it is easy to get. Meaning, the organisers likely do not make any money from the festival. Perhaps, it is for the love of the thing. It would be fascinating to interview half a dozen organisers and ask them the same questions.

Very soon after the boom in India, Lahore and Karachi also put up their festivals, which are going strong as far as I know. I went there about three years ago and found them similar to and different from the ones in India.

The differences were minor and major. The levels of security were ridiculous (but justified of course). There were three separate layers and many men with automatic weapons. There were many more Urdu sessions than we have Hindi or Gujarati or other language ones in India. And, in fact, the Urdu ones were often the largest and best attended. It may have been noticed by some readers who know Pakistanis or Pakistan that the biggest difference between our middle-class and theirs is that theirs is properly bilingual.

Lastly, it seemed to me that there was more serious material that was being discussed in most of the panels. One might argue that this is because they have had many more serious issues to deal with over the years than we have, but even so. The difference is manifest.

The similarities were that often, in the guise of literature, the festival was pushing Bollywood. Either, there were sessions on the Pakistani singers of yore, such as Noor Jahan (since they don’t have much of a film industry at the moment), or current Indian ones. And, of course, the other similarity is that the majority of the audience did not seem familiar with the works of the people they had come to listen to.

They had come for an outing in the spirit of entertainment, which makes the use of the word festival for these events so appropriate.

)