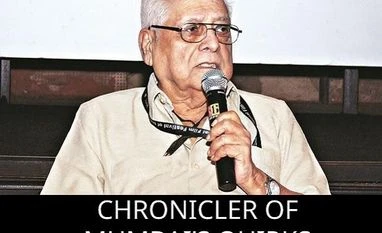

Filmmaker Basu Chatterjee’s oeuvre will forever be associated with the city of Mumbai. Few directors captured the granular realities of the sprawling metropolis and its people with the sustained insight, empathy and good humour that he brought to the task. It wasn’t the grit and grime that he was interested in. He was drawn by the quirks and foibles of Mumbaikars.

While the city may have dominated his cinematic output, Chatterjee’s versatility as an accomplished storyteller was phenomenal. From solemn literary adaptations to serious-minded chronicles of middle-class lives and struggles, and from light-hearted comedies centred on human idiosyncrasies to intense dramas with a deep social core, he delivered a staggeringly wide variety of films in a career that spanned nearly five decades.

In the late 1990s and in the noughties, by which point his career in Mumbai had ground to a halt, the pioneer of Mumbai’s middle-of-the-road cinema made a few Bengali films. Among them were the Indo-Bangladeshi co-production Hothat Brishti (Sudden Rain, 1998) and Tak Jhal Mishti (Bitter Spicy Sweet, 2002). Would you believe that Chatterjee, in his 80s, tried his hand at a David Dhawan-style comedy in his mother tongue? The film that resulted, Hochheta Ki (What’s Going On, 2008), was bound to fail.

What stood out in the Ajmer-born Chatterjee’s work — it includes unforgettable television serials like Rajani, Kakkaji Kahin and Byomkesh Bakshi, all for Doordarshan — was a streak of impish geniality. Readers of Russi Karanjia’s Blitz saw sparks of it during Chatterjee’s 18-year stint at the weekly tabloid as a cartoonist and illustrator.

He assisted Basu Bhattacharya on Teesri Kasam (1966) and Govind Saraiya on Saraswatichandra (1968) before becoming an independent director. His debut, Sara Akash (1969), was unlike any other film that the prolific director would make. It was a seminal work, playfully experimental, set in a conservative middle-class Agra family and based on the first part of a novel by Rajendra Yadav.

With Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome and Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti, both made in 1969, Sara Akash inaugurated what came to be known as the Indian New Wave. Incidentally, all three films were shot by K K Mahajan, fresh out of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) Pune. The cameraman won a National Award for his fluid cinematography in Sara Akash.

Chatterjee’s second film, Piya Ka Ghar (1972), a remake of Raja Thakur’s Marathi feature Mumbaicha Jawai, was far closer in spirit and substance of the rest of his career. It told a comic tale of a newly married middle-class couple who struggles for privacy in a cramped Mumbai apartment occupied by the groom’s joint family.

Chatterjee went on to draw the urban expanse of Mumbai and the workings of middle-class life in the city into his subsequent films, most notably in Rajnigandha (1974) and Chhoti Si Baat (1976), both starring Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha. In the former, the character played by Sinha is a visitor from Delhi who is shown the sights of Mumbai. In the latter film, too, a love triangle develops in recognisable spaces — bus stops, offices, busy streets and marketplaces of the bustling megalopolis.

Nobody ever captured the Mumbai monsoon quite as memorably as Chatterjee. In Manzil (1979), starring Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee, he set Lata Mangeshkar’s voice free in “Rimjhim gire saawan”, doing away with the norm of the heroine lip-syncing the number. The song acquired an anthemic force as a result. Moushumi Chatterjee and the song made it into the 2014 documentary film Monsoon, Canadian-Icelandic director Sturla Gunnarsson’s exploration of the centrality of the rains in Indian life and culture.

Just as much as Mumbai, literature sustained Chatterjee’s cinema. A large chunk of his films were screen adaptations of the works of novelists and short story writers, principally in the Bengali language. Chitchor, made in the same year as Chhoti Si Baat, emerged from a short story by Subodh Ghosh. Swami (1977) and Apne Paraye (1980) were Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay adaptations; Dillagi (1978), starring Dharmendra and Hema Malini, was based on a novella by Bimal Kar; and Hamari Bahu Alka (1982) owed its inspiration to a Manoj Basu story.

Chatterjee went further afield and worked with stories written in other languages as well. Rajnigandha was based on a short story by Mannu Bhandari; Triyacharitra (1994), one of his late-career films starring Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri and Rajeshwari Sachdev, was adapted from a Shivmurti story; and Chakravyuha (1979), which Rajesh Khanna starred in and produced, was a thriller based on Scottish writer John Buchan’s 1915 novel, The Thirty-Nine Steps.

Man Pasand (1980), produced by and starring Dev Anand as the Indian avatar of Professor Henry Higgins (from the George Bernard Shaw play Pygmalion and the 1964 Rex Harrison-Audrey Hepburn musical My Fair Lady), was derived from P L Deshpande’s Marathi play Ti Phulrani.

The fact that Chatterjee was clued into international cinema is borne out by at least two remarkable films of his career — the deeply melancholic Us Paar (1974) and the powerful jury drama Ek Ruka Hua Faisla (1986). The former adroitly indigenised the 1967 Czech film, Romance for Bugle, adapted by director Otakar Vávra from an epic poem of the same name written in 1961 by Frantisek Hrubin.

In Ek Ruka Hua Faisla, a remake of the 1957 Berlin Golden Bear-winning Sidney Lumet film, 12 Angry Men, Chatterjee extracted a slew of remarkable performances from a cast of National School of Drama-trained actors, led by the outstanding Pankaj Kapur. But no less astounding were the other actors (M K Raina, K K Raina, S M Zaheer and Annu Kapoor) playing the bickering jurors tasked with deciding the fate of a boy accused of stabbing his father to death.

The authenticity that Chatterjee imparted to the crackling jury proceedings was a trait that defined most of his better films. Whether he was portraying the Parsi community in Khatta Meetha (1978), the Anglo-Indians in Baaton Baaton Mein (1979) or Mumbai chawl-dwellers

in Kamla Ki Maut (1989), in which a crisis erupts when a 20-year-old unmarried girl commits suicide on learning that she is pregnant, he rarely failed to get the tonalities of a milieu right. A far cry from the ersatz constructs of commercial Hindi cinema of the 1970s and 1980s.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)