The first edition of the ChessMine Rapid & Blitz tournament in Bengaluru showcased a new paradigm in Indian chess. ChessMine offered over Rs 6 lakh in prize money across two speed events held from August 5 - August 7.

The rapid was a nine-round affair played at 15 minutes with a 10 second increment on every move. The blitz consisted of 11 rounds played at three minutes with two seconds increment per move. The competition was ferocious.

The rapid drew a field of 466 players with 15 Grandmasters. Top seed was India’s No 3, 22-year-old Vidit Santosh Gujrathi. The blitz drew 245 players. Short controls allowed for six rapid rounds in a day, and for 11 blitz rounds in a day.

Quite apart from the generous prize money and decent playing conditions, the short format and scheduling were crucial elements for heavy participation. At least 400 players were younger than Gujrathi. Half of the field, or more, was short of voting age. There were also “hobby players” — bankers, lawyers, doctors and IT professionals renewing their love for the game they cannot play during the work-week.

ChessMIne is one of several recent weekend events. Weekenders not only allow kids to play, but adults can also have a bash, often alongside their children. These events are also easier on organisers since expenses like hall rentals and hotel bookings are minimised.

India is now a chess power, with nearly 50,000 rated players and 48 Grandmasters. In the last two Olympiads, Indian teams took third place (Tromsø 2014) and tied for fourth (Baku 2016) in the Open section, while the Indian women tied for fourth at the last Olympiad (Baku 2016). More weekenders may help turbo-charge desi chess.

Three young players who played at the ChessMine have been on Business Standard’s radar for a couple of years. We profiled them in 2015 (

“Who will replace Viswanathan Anand?”) and they’ve made considerable progress since.

Two Chennai Grandmasters, Aravindh Chithambaram and Murali Karthikeyan, are now both 17 and hailed as seriously talented Grandmasters. Nihal Sarin of Thrissur, Kerala, is 13 and one of the world’s youngest International Masters. He’s well on his way to becoming a Grandmaster.

Along with the splendiferously named Praggnanandhaa R, this trio is likely to ensure that the tricolour flies high in the chess arena for decades to come. Pragga, who celebrated his 12th birthday this month, became the youngest player to ever achieve the International Masters title in 2016, aged 10 years and 10 months. He has seven months to make it to Grandmaster and break Sergey Karjakin’s record to become the youngest-ever Grandmaster.

In 2015, when Business Standard profiled this trio, Chithambaram and Karthikeyan were fledgling Grandmasters and Sarin was untitled. Since then, Karthikeyan has won back-to-back national championships and represented India at the Olympiads. Chithambaram has jumped several levels in strength. The duo from Chennai has exactly the same Elo rating and they’re ranked 15th-16th on the World Junior list (which includes 20-year-olds). Sarin is No 78 on that list and Pragga is No 76.

Sarin started with a fantastic six straight wins in the rapids. But he fell off the pace with three draws and a last round loss to eventual champion, Grandmaster Abhijeet Gupta who scored 8.5/10. If Sarin had won that game, he would have tied for first place. The loss pushed him down to joint 14th-30th with 7.5 points. That’s an indication of just how hard-fought ChessMine was.

Chithambaram also tied for 14th with 7.5 points, while Karthikeyan (8) tied for 6th-13th. The top-seed Gujrathi (7.5) himself landed outside the rapid prize list though he did win the blitz (10 points from 11 games). Karthikeyan (8.5) came sixth in the blitz and Chithambaram and Nihal (both 7.5) tied for 17th-34th.

Not such a great performance you might think, for three such highly-rated prodigies. But that also reinforces the utility of such competitive events. Plus, rapid and blitz play guarantees frequent blunders. As the seconds run out, mistakes happen.

None of the trio seemed disheartened. They are all pragmatic and experienced enough to know that every event doesn’t go your way. In fact, all three come through as astonishingly mature young men (I’m using that word advisedly).

Chithambaram and Karthikeyan travel on their own. They’re adept at mental currency conversions and unfazed by linguistic difficulties and the hazards of “adjusting” to unfamiliar food and strange climates. Sarin is more likely to travel with a parent. But he’s also comfortable with belonging to the guild of professional chess players.

Underneath, there is absolute focus. The trio work hard on improving specific aspects of the game. Their analysis mode is always “switched on”. Karthikeyan works to a regular schedule, with regular hours allocated. Chithambaram works in bursts spending very long hours sometimes. Sarin claims he only works when he feels like it but that is more or less 24x7.

All three are “Fritz kids”. They don’t use physical chessboards except when actually playing a tournament. (Fritz is the brandname of a popular chess-playing program from Chessbase, Germany.) They use mobiles to access games played live from around the world. They “speed-read” game scores. (Many non-chess players think the ability to follow a chess game “blind” is magical. In reality, it’s about as mundane as looking at a musical score and “hearing” the tune. Millions play blind chess as easily as millions read musical scores.)

Sarin scored his first Grandmaster norm in Fagernes, Norway this April, when he came fourth at the TV2 Fagernes Open. His next goal is to score a second norm, and if required, a third. In between chess and school, he indulges a puckish sense of humour, composing odd little problems and mental teasers.

According to the Grandmaster experts of the Chessbase team, who worked with him for a few days in Germany, he’s the most extraordinary talent they’ve seen since Magnus Carlsen. Sarin says, “That work paid off because I learnt some endgames.” He scored his Grandmaster norm just after that stint. He was 12 years, nine months old — five months younger than Carlsen when the world champion scored his first norm.

His father, Abdul Sarin, says, “We’ll let him play wherever it seems good. Once his talent was clear, we asked for advice on how to nurture his career, which events he should play abroad, where he should go as a spectator, et cetera.” It’s not easy. The Sarins are doctors in government service and they have to juggle leave and school commitments.

Chithambaram’s mother, Deivanai, is a single parent. She relocated from Madurai to Chennai to further her son’s career. She works as an insurance agent. Chithambaram has a stipend from ONGC and he works with Grandmaster R B Ramesh at Ramesh’s coaching centre, Chess Gurukul. He says he just wants to push up his rating, play good chess and learn opening theory, since his lack of early coaching has led to gaps in his knowledge.

Karthikeyan is preparing for the World Cup in September. That’s a 128-player Wimbledon-style knockout with mini-matches. His opening match is with the highly-rated and experienced Francisco Vallejo Pons of Spain and the Chennai lad is the underdog. Whatever happens there, he also hopes to push his rating up, gradually.

Chess is a hyper-competitive sport with hundreds of strong, hungry players. It’s unforgiving — one error can ruin hours of hard work. There’s no telling where these three extraordinarily talented players will end up. But there’s also no doubt that they do whatever it takes to maximise their talent.

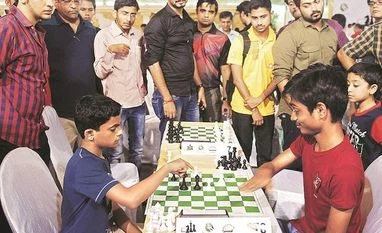

Nihal Sarin (left) and Aravindh Chithambaram at the Rapid & Blitz tournament in Bengaluru. Photo: Saggere Radhakrishna

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)