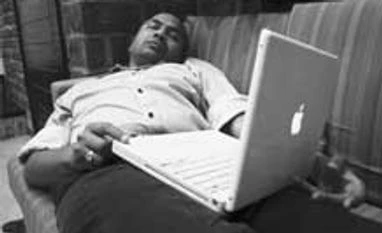

There may be a link between later bedtimes and weight gain, new research suggests.

Researchers studied 3,342 adolescents starting in 1996, following them through 2009. At three points over the years, all reported their normal bedtimes, as well as information on fast food consumption, exercise and television time. The scientists calculated body mass index (BMI) at each interview.

After controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, the researchers found that each hour later bedtime during the school or workweek was associated with about a two-point increase in BMI.

The effect was apparent even among people who got a full eight hours of sleep, and neither TV time nor exercise contributed to the effect. But fast food consumption did.

The study, in the October issue of Sleep, raises questions, said the lead author, Lauren D Asarnow, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. "First, what is driving this relationship?" she said. "Is it metabolic changes that happen when you stay up late? And second, if we change sleep patterns, can we change eating behaviour and the course of weight change?" The scientists acknowledge that their study had limitations. Their sleep data depended on self-reports, and they did not have complete diet information. Also, they had no data on waist circumference, which, unlike B.M.I., can help distinguish between lean muscle and abdominal fat.

Researchers studied 3,342 adolescents starting in 1996, following them through 2009. At three points over the years, all reported their normal bedtimes, as well as information on fast food consumption, exercise and television time. The scientists calculated body mass index (BMI) at each interview.

After controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, the researchers found that each hour later bedtime during the school or workweek was associated with about a two-point increase in BMI.

The effect was apparent even among people who got a full eight hours of sleep, and neither TV time nor exercise contributed to the effect. But fast food consumption did.

The study, in the October issue of Sleep, raises questions, said the lead author, Lauren D Asarnow, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. "First, what is driving this relationship?" she said. "Is it metabolic changes that happen when you stay up late? And second, if we change sleep patterns, can we change eating behaviour and the course of weight change?" The scientists acknowledge that their study had limitations. Their sleep data depended on self-reports, and they did not have complete diet information. Also, they had no data on waist circumference, which, unlike B.M.I., can help distinguish between lean muscle and abdominal fat.

©2015 The New York Times News Service

)