These quick online sessions indicate her influence. A Live event featuring one client, high-profile actor Alia Bhatt, two years ago amassed 1.3 million views and 16,000 “likes”. During a recent broadcast about kids’ lunch ideas that was no longer than eight minutes, over 100 comments dropped in and the “likes” flew to 500 in real time. The reactions ranged from eager greetings to urgent questions about what to give babies suffering from lactose intolerance and gastroesophageal reflux disease. By the next day, the post, in which she simply suggested packing ghee-roti-jaggery and tadka-chawal in steel tiffins rather than plastic ones, had been shared more than 1,000 times. At least half a million people follow her each on Facebook and Twitter.

Many forces contribute to this popularity, first among them being her closeness to celebrities — she is “Rujju” to actor Kareena Kapoor. She also has an animated style of talking, and an approach to nutrition that appears less alarmist and more permissive than that of some peers.

She mentions having studied in Mumbai-based universities, the Himalayas, and institutes in Australia and Canada, but her constant refrain is that there is no wisdom greater than grandmom’s common sense. Diwekar’s methods, which are an updated version of the ancient Indian philosophy known as mitahar, advises that one eat local and seasonal food, and celebrate homegrown culinary knowledge.

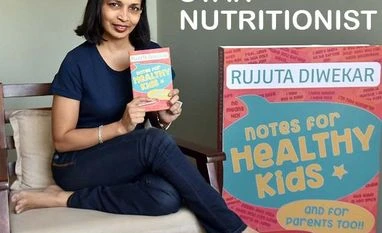

Her eight books, which are in effect versions of each other, promote traditional concepts of diet and activity over Western ones. The latest, a 256-page-long Notes for Healthy Kids (published by Westland), outlines eating habits and charts for children. This is coupled with a disdain for modern parenting tropes like allowing children to watch videos during meals or feeding salad greens to babies, which frequently make Diwekar nauseous. After witnessing the latter scenario unfold at a café in Bengaluru, Diwekar wrote, “I forced a smile but I wanted to strangle my friend.”

The tone is casual and conversational because casual conversations are where her books are born. “The main sensory organ I use to write is my ears,” she explains, adding in the same blithe manner of her writing, “There are not too many books that I have read.” Her work would seem read widely though, available in languages including Gujarati, Telugu and Tamil. She has catchy mantras, such as choose “local, not low cal”, or “what is good for their bottom-line is not good for your waist-line” when mentioning the profit-driven food industry.

Her books, priced between Rs 150 and Rs 350, and social media posts are the only ways to access her advice for most people, compared with the prohibitively expensive paid consultations. Subscription costs for her programmes have risen to an astonishing Rs 10 lakh for a year, in which clients can see her twice a month. For the most basic service, which is a consultation with Diwekar’s team members for up to three months, one must part with Rs 1.8 lakh. Round the year, she conducts week-long yoga retreats in picturesque venues that cost roughly Rs 1.5 to 2 lakh, and corporate talks for anywhere between Rs 3 lakh and Rs 9 lakh.

People’s willingness to pay for her commonsensical tips has enabled her to shift to the tony Khar area several years ago, after initially operating out of Andheri. Guests are typically offered tea, coffee, or kokum sherbet here and adding sugar is encouraged. She first shot to fame in 2008, launching a health book around the release of the film Tashan, for which she helped Kapoor achieve a “size-zero” look. Her work with celebrity clients had, in fact, begun with Lali Dhawan as early as 2000, when she was fresh out of studying sports nutrition and training as a fitness instructor at Talwalkars Gym.

Diwekar’s attempt to lift complications and restrictions from nutrition has sometimes backfired, with those in the medical fraternity raising red flags. She claimed, for example, that those with diabetes can eat mangoes, that mangoes are actually good for them because of their low glycemic index, and that they help maintain insulin sensitivity. “Mango per se may be considered in rationed amounts and never with the meal or after a meal as it may add to the total glycemic load and glycemic index of the meal,” notes Jagmeet Madan, national president of the Indian Dietetic Association. Anil Bhoraskar, a long-time professor of diabetology who practises at Mumbai’s Asian Heart Institute, says diabetics may eat half a cut mango but it must not be in the form of juice and it should be away from meals by at least an hour. “It is a good source of fibre and vitamin A but I would not say that a diabetic must eat mangoes or that it will cure the disease.”

In another instance, she suggested that ghee lowers the glycemic index of the food to which it is added, and further that deep frying food in ghee is a healthy practice compared with baking or air-frying. “Adding fat to a food blunts the glycemic response but the question is which fatty acids are contributed by the fat that is added and how much is the quantity added?” notes Madan. Fats from invisible sources like nuts and oilseeds are better, she contends. Bhoraskar notes that one to two teaspoons added on top of food is acceptable but deep frying is not advisable given ghee’s high content of saturated fats.

Diwekar’s advice often includes no such caveats, as she believes she should never have to tell one when to stop, and that counting calories is unhealthy. She is averse to “nutritionism” or the practice of linking the value of each food specifically with its nutrient profile. In the absence of any pointers on food portions, however, the easy-going advice might validate desires to indulge oneself. The responses from followers to her posts are telling. People often seek approval for their favourite foods — “Do you eat chaat or golgappa?”, “Is butter good?” — and celebrate any permissions to eat — “Got another reason to binge on the tasty gajar ka halwa” or “Khao bindas”.

“There are general guidelines for people without conditions and guidelines specific to people with certain conditions,” observes Hemalatha R, director of the National Institute of Nutrition, cautioning that people must not confuse the two. She says rules for regulating the sharing of nutrition advice are in the process of being drawn. “People who share tips on social media should refer to the source, either Dietary Guidelines for Indians, or guidelines of FAO, or WHO. Then users can be that much more confident.”

Occasionally, Diwekar quotes studies to corroborate her views. She cited the USDA 2015 guidelines to back her claim that cholesterol is not a “nutrient of concern”. The same USDA guidelines advise limited intake of saturated fats, something contained in ghee. In opinions shared in various writings and videos, Diwekar says foods like sugar and full-fat milk are casualties of the weight-loss industry which needs a new villain every year. The weight-loss industry has in turn been a villain in her universe. “There would be no place for my voice had it not been for fad diets. Common-sense eating would have been out of fashion,” she shrugs.

Unlike most influencers, her channels do not have paid posts, brand endorsements or collaborations. Several of her ideas, while couched in casual language, are logical. She argues that they are not seen as “scientific” because “we associate science with boredom and with language that we cannot understand”. To win confidence at a time when pseudosciences are at large, however, there may yet be value in causing boredom.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)