If you are among the more than 50,000 people who will run the New York City Marathon on Sunday, you know that training, eating right and getting a good night’s sleep are some of the keys to setting a personal best. But an analysis of more than 4.7 million finishing times from 20 years of data on almost 900 marathons — including those in New York, London, Chicago, Boston, Berlin and the Olympics — shows how much your time can be affected by another factor: temperature.

The fastest times are run on days when the average outdoor temperature is in the 40s. (Humidity data were unavailable.) Current weather forecasts suggest that the average temperature in New York on Sunday will be about 61 degrees Fahrenheit (around 16 degrees Celsius), which the data show will add about 12.5 minutes to the typical finisher’s time, relative to a day in the 40s.

In a sport in which competitors work tirelessly to improve their times by a few seconds, that is a big effect. What’s more, the relationship between temperature and finishing times is actually nonlinear — meaning that the effects of temperature strengthen as it gets warmer.

Temperatures in the 50s increase the typical finishing time by only about five minutes, relative to a day in the 40s. On the other hand, days in the 70s would cause finishing times to be slower by 19 minutes; in the 80s, times would be 33 minutes slower.

And while the biggest impacts show up in the performances of amateurs and weekend warriors, elite runners are not immune to these effects. When considering the top 20 finishing times at the largest marathons, the assessment found that temperatures in the 50s did not slow them, relative to days in the 40s. But temperatures in the 60s and the 70s increased their times by three and four minutes, respectively.

Since the temperature has such a big effect on times, would it make sense to adjust official records for the weather? If this were done, five of the 25 fastest men’s marathon times would beat the current adjusted world record. Indeed, three of them would be more than two minutes faster.

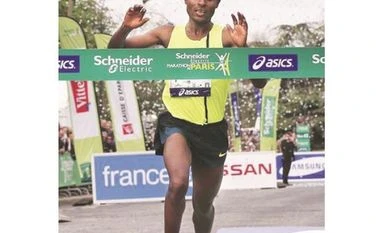

The current world-record holder is Dennis Kimetto from Kenya, but the temperature-adjusted record-holder would be Kenenisa Bekele from Ethiopia. The second-fastest time would belong to the Ethiopian Tamirat Tola.

Adjusting times for temperatures would lead to smaller changes among women. Paula Radcliffe of Britain (who has won the New York race three times) would remain the record-holder.

The interactions between climate and a sport like long-distance running are only going to get more pronounced as the climate changes. Over the last 50 years, the temperature has exceeded 60 degrees on just 5 per cent of the days during the first week of November, when the New York race is typically held. By 2050, this is projected to rise to 18 per cent of days, and by 2090 it is expected to be 38 per cent.

How will runners and organisers react? National governments, city planners and large corporations are all realising that a warmer world will force them to change the ways they do business.

Marathons will be no exception. The organizers of the New York race will probably not want their event to be one where it is difficult, or perhaps even impossible, for people to set their personal best or to lower the world record. So they may want to adapt by moving the marathon to later in the year.

At the same time, runners may switch from the New York City Marathon to others held in cooler climates to find the perfect temperature at just the right time of year. Could a Montreal Marathon be among the world’s most prestigious by 2050?

Athletic equipment companies will surely develop new technologies to aid adaptation as well. For runners, the breathable mesh and cooling towels of today could easily be traded in for shirts with built-in air-conditioners. Seem far-fetched? They already exist. Indeed, I was one of the authors of a recent study of just how powerful a role technology can play in helping people adapt to warmer temperatures.

For example, the rise of air-conditioning has reduced the mortality consequences of extremely hot days in the United States by more than 70 per cent since 1960.

© 2017 The New York Times

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)