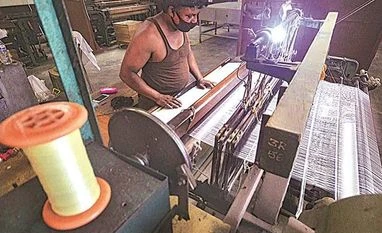

Last Friday, India’s largest garment hub, Tiruppur, came to a standstill with owners of over 6,000 knitwear and garment and allied industries downing shutters and sitting on a hunger strike. They were demanding relief on rising cotton yarn prices for the last 10 months and the ban on its exports. The issues they were protesting were evidently serious enough to agree to collectively absorb a loss of around Rs 120 crore on that day.

At the heart of the problem is soaring input costs — of cotton and cotton yarn — which has caused a 20 per cent price rise in garments despite the pandemic.

That is why the government’s decision to have a uniform goods and services tax (GST) at 12 per cent for the textile and apparel sector (on manmade synthetic fibre, manmade fibre yarn, manmade fabrics and apparel) raised eyebrows. The government’s decision was prompted by the need to realign input costs, which were typically higher than the finished product. Before the decision, the rate for manmade fibre was 18 per cent, manmade fibre yarn was 12 per cent and manmade fibre fabrics was 5 per cent.

But a large section of the industry sees the GST decision, which will raise the price of fabrics, as an additional dent on the garments industry that is suffering on account of the volatility in cotton and cotton yarn prices. From January 1, 2022, consumers may have to pay 6 to 7 per cent more on readymade garments on account of GST, which, the industry anticipates, could cause a dip in demand, especially on garments below Rs 1,000. This means that 85 per cent of the industry, mainly micro small and medium industries, will be the losers.

Normally, any increase in the price of cotton by Rs 1,000 per candy (one candy = 254 kg) would lead to an increase of Rs 4 per kg of yarn. A sharp increase in the prices of the many variants of cotton over the past year (Shankar-6 by 80 per cent; 40s combed hosiery yarn by 58 per cent; DCH-32 by 126 per cent; 80s yarn by 38 per cent) caused a spike in cotton yarn prices by an average of 60 per cent.

Overall, from January to November, yarn prices reportedly increased from Rs 220 per kg to around Rs 350. Cotton accounts for around 80 per cent of the yarn cost and yarn cost makes for around 25 per cent of the cost of garments and made-ups (the term refers to articles manufactured from any type of cloth). Spinning mills are able to absorb only a small percentage — about 20 per cent — of the costs, thanks to long-term relationships with the downstream sector, but the rest has to be passed on to the consumer.

This input price rise is in tandem with sharp rise in international cotton prices, which are up by 74 per cent. “The impact of the increase in GST is even more worrisome as prices may go up further for end-users.

The worst sufferer is the consumer as prices have already moved up by 20-25 per cent due to inflation in cotton and yarn,” said Sanjay Kumar Jain of Delhi-based TT Ltd, which has its main manufacturing unit at Tiruppur.

Experts indicate that a decline in demand (on account of higher consumer prices) may have a long-lasting impact on the future of the textile industry. According to an OECD-FAO report on Agriculture Outlook 2021-2030, India will continue to lead cotton production by contributing to around 25 per cent of the global share in 2030. The country is also expected to be next to China in terms of consumption. The import duty on cotton imposed by the government, too, had an impact on prices.

There is a section in the value chain that blames the Cotton Corporation of India (CCI), which is in charge of the procurement of cotton, for the price rise in cotton yarn in the domestic market. Tiruppur Exporters Association (TEA) has already approached Prime Minister Narendra Modi, accusing cotton traders, global players and CCI of “unjustifiably” manipulating the prices through “hoarding”.

In the letter, TEA President Raja M Shanmugham had said that multinationals are making use of CCI-procured cotton stock in their favour by booking in advance with CCI on a huge volume basis.

The industry body had sought government intervention in this regard.

It is unclear how far this accusation is true. An industry expert has pointed out that, "The CCI price increase is in tandem with international prices. Their prices are below the spot prices locally. If some players see Indian cotton cheaper, they can buy and sell it abroad. Nothing illegal about it.” But a spinning industry official opined that CCI should stop selling their procured product on exchanges and also to traders. The association thinks CCI should supply to textile mills, mainly MSMEs, directly rather than fixing a higher benchmark to the quantities, which may benefit corporate traders in cotton.

In a meeting held with the government on November 18, the Confederation of Indian Textile Industry also demanded the removal of the 5 per cent basic customs duty and 5 per cent agriculture infrastructure development cess levied on cotton imports to change the market sentiment in the short run and enable the industry to have a level playing field and avoid speculation during the lean season.

The government is unlikely to intervene at the moment. Commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal had made it clear the government would intervene only if the stakeholders “don't trade and sell in a fair and free manner”, said sources who attended the meeting. “Resolve the cotton pricing issue in the spirit of collaboration rather than competition,” the minister directed the industry, according to sources.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)