By 2023, the Indian Railways plans to have private passenger trains running on its network at a maximum speed of 160 kilometre an hour (kmph). Equally ambitious is its target to have a bullet train running between Ahmedabad and Mumbai at a maximum speed of 320 kmph by December 2023. The focus of the government-run Railway Board, the apex decision- and policy-making body for the Indian Railways, is clearly on passenger travel — getting in newer operators while giving an air travel feel on railway tracks. In this quest for speed, the bread and butter for the railway system, freight traffic, which accounts for 65 per cent of its revenues, seems to have lost traction.

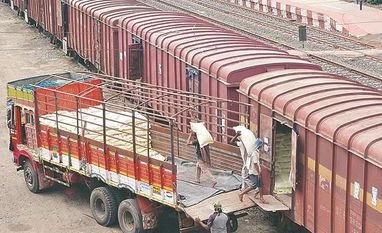

Augmenting freight operations through better marketing, cheaper tariff and discount packages has been on the railway agenda. It has been less active in nudging the Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India Ltd (DFCCIL), a project more than 14 years in the making that was expected to revolutionise freight movement and help the Railways regain the market share lost to private road transport over the years.

Conceived by the United Progressive Alliance, the two freight corridors were to be completed in 2016-17, but the deadline was shifted multiple times: March 2018, April 2020, December 2021 and now June 2022. So far, only the 306-km Rewari-Madar has been commissioned.

The new deadline, too, looks unlikely, not least because DFCCIL has been without a managing director since August when Anurag Sachan retired. His replacement, Ravindra Kumar Jain, was appointed only on November 27 though he was selected much earlier. Jain's appointment will help in continuity since he was monitoring the works from Railway Board, said an official.

The pace of execution, according to the official, picked up after a ministerial-level intervention in August. “Trial runs in various sections of the dedicated freight corridors (DFCs) are getting over and commercial operations are expected to start from the week starting December 1 in a phased manner. Business and commercial tie-ups are being established and the Railways hopes to go full steam ahead by January,” he added.

DFCs are designed to allow freight trains to travel at 100 kmph (from the current average of 23.6 kmph), according to the DFCCIL website. A business plan chalked out by the corporation for 2020-2024 anticipated that traffic of 178,054 million net tonne kilometre (NTKM, which expresses a tonne of cargo moved over a distance) would be available on the eastern DFC at a CAGR of 4.5 per cent by 2022, and 1,28,064 million NTKM on the western DFC at CAGR of 7.7 per cent.

This is clearly not the direction in which either arm of the DFC is moving for two reasons: The physical network is incomplete and growth in the cargo business has been not strong enough for the Indian Railways to push the traffic onto a separate arm.

The Railways official contended that “significant progress has been made in this financial year with 500 km of the route commissioned”. Another 500 km will be commissioned by March 2021, he added. Further, he said, along the western arm, three Gujarat ports will be connected by March 2021 and freight trains will start moving on the corridor. Connection to the JNPT will be completed by June 2022. According to the latest target, 40 per cent of the DFC will be operational by next year.

In various fora, the corporation has claimed that some land-related issues remain in Maharashtra, which are being sorted out with the state government, but experience has shown that even a small patch can create hurdles. Also, the deadline for physical construction has been pushed to 2022 from December 2021 after DFCCIL cited delays by contractors in executing work. Some 2,000 km of corridor will be operational by March 2021 with overhead equipment and signalling system.

Considering that DFCCIL was incorporated in 2006, every delay is adding to the cost and time overrun. The fact that it is Indian Railways’ largest infrastructure projects taken up at a cost of Rs 81,459 crore has, strangely, not been a reason for the government to prioritise it despite the involvement of the World Bank and Japanese International Co-operation Agency.

The 1,504-km western DFC runs from Jawaharlal Nehru Port in Mumbai to Dadri in Uttar Pradesh, and the 1,856-km eastern DFC is from Sahnewal near Ludhiana in Punjab to Dankuni in West Bengal. Khurja, Kanpur, Rewari, Dadri, Ajmer, Palanpur and Gujarat ports on the western arm will be connected by the end of 2021. By March 2022, most of the sections will be commissioned and the remaining eastern and western arms will be commissioned by June 2022.

During a review meeting on August 24, Union railway minister Piyush Goyal asked DFCCIL to allow the projects contractors, which included GMR, Alstom, Tata Projects, Hitachi and Texmaco Rail & Engineering, time because of the Covid-19 pandemic. According to an official statement, DFFCIL was also asked to compensate the loss of time owing to the national lockdown. Since the meeting, the Railway Board has been monitoring the project and all contractors. Resolution of all issues, including coordination with the states, is being speeded up with a weekly progress report being submitted.

While the role and scope of DFCCIL is clear, the rules of engagement between the Indian Railways and the corporation are equally important for any meaningful take-off of commercial activity. This relationship is governed by a concession agreement signed in February 2014. Under it, DFCCIL will earn a track access charge from the Indian Railways and a portion of Indian Railways revenue will be shared based on the actual freight volume moved.

A report prepared by KPMG three years ago also examined the issue of non-discriminatory access for DFCCIL. It has come up with options for institutional arrangements for providing non-discriminatory access for rail freight train operations and suggested a system based on international experience including a methodology for setting track access charges. The report also gave suggestions on institutional arrangements for licensing, regulation of traffic, capacity allocation and safety, including the methodology for calculating track access charges in order to accommodate multiple users. This indicates that private freight train operators, including container trains, could also use the DFC.

Delays, however, have meant operations will begin when the country is in an economic recession. A falling GDP may not augur well for the high-cost project, but it could well gain from the low expectations vested in a interminably delayed project.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)