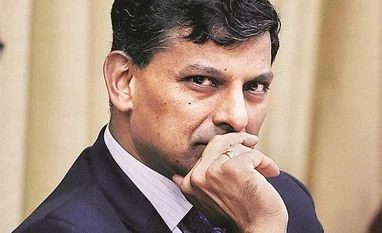

Former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Raghuram Rajan has reiterated his concerns over the bureaucracy impinging on the powers of the central bank. He has also said it should be made clear that the RBI chief is not just another bureaucrat.

“There is a danger in keeping the position (of the RBI governor) ill defined, because the constant effort of the bureaucracy is to whittle down its powers,” the 23rd RBI governor has written in his book, I Do What I Do.

“This is not a recent phenomenon...” the former governor has written. “The RBI risks becoming dangerously weakened, as successive governments and finance ministers have misunderstood its role.”

“The RBI governor, as the technocrat with the responsibility for the nation’s economic risk management, is not simply another bureaucrat or regulator, and efforts to belittle the position by bringing it into the bureaucratic hierarchy are misguided,” Rajan wrote, adding: “Clarity about the RBI’s role, and a clearer assertion of its independence, would be in the nation’s interest.”

This is probably the first time Rajan has spoken so clearly on the issue, highlighting a clear divide between the finance ministry and the RBI. In the section quoted above, he has clarified some points he made in his last speech as RBI governor on September 3, 2016, at St Stephen’s College in Delhi.

In that speech, Rajan had said, it was dangerous to have a “de facto powerful position with low de jure status”.

Rajan has also elaborated on the lack of a clear definition of the central bank governor’s position in the government. The governor’s salary was at par with that of Cabinet secretary and he was appointed by the prime minister in consultation with the finance minister. “The governor’s rank in the government hierarchy is not defined but it is generally agreed that decisions will be explained only to the prime minister and the finance minister,” he had said in his speech. None of this, including the informal understanding of having the powers to make decisions for macroeconomic stability, should be changed, he had said. He added if these issues were ever revisited, “there may be some virtue in explicitly setting the governor’s rank commensurate with her position as the most important technocrat in charge of economic policy in the country”.

In his book, Rajan also touched upon his interview, in which he compared India’s economic rise in a weak global environment as something like “in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king”. It was greeted with controversy. Rajan, in his book, writes he was “finally fed up of the perhaps motivated search for controversy”. He later clarified his usage of the phrase in a subsequent speech, but even that speech was also somewhat misinterpreted.

Rajan reveals in his book that he thought “there was no need to clarify further. Those who did not wish to understand could not be forced to do so”.

The former RBI governor has written that had he known his “Hitler” remark on a speech would turn out to be so controversial, he would have never used the analogy and in no way was it connected to any specific administration.

In an honest admission, Rajan writes his first speech after assuming office, in which he underlined a reforms agenda and opened up a scheme of dollar deposits from non-resident Indians, was a “facade of confidence to assure the public and investors that the RBI knew what had to be done”. The purpose was to send out a message that “India had strong institutions like the RBI that could push reforms forward even when Parliament was stalled, and international investors should not write India off”.

The message worked and the rupee, which had breached its record low of 68.87 a dollar a month before, stabilised and started strengthening.

In the book, Rajan is also candid about demonetisation and said he was not party to the decision. He claims to have warned the government that the short-term cost of demonetisation would outweigh the long-term benefits and that there were better ways of achieving the same objective, without banning notes outright.

Rajan was then asked to prepare a note, which the RBI put together. “It outlined the potential costs and benefits of demonetisation, as well as alternatives that could achieve similar aims. If the government, on weighing the pros and cons, still decided to go ahead with demonetisation, the note outlined the preparation that would be needed, and the time that preparation would take. The RBI flagged what would happen if preparation was inadequate”.

The government then set up a committee, attended by the deputy governor in charge of currency, to consider the issues. “At no point during my term was the RBI asked to make a decision on demonetisation,” Rajan writes.

Rajan demitted office on September 3, 2016. Demonetisation was announced on November 8.

This indicates, even at best, the RBI under Rajan’s successor, Urjit Patel, would have got a maximum of two months to prepare for demonetisation. The period could, in fact, be much less, considering the secrecy required to make it a success.

In its annual report, the RBI has claimed that out of currency with value of Rs 15.44 lakh crore that was banned, Rs 15.28 lakh crore was back in the banking system. This has sparked a nationwide debate on whether demonetisation was a success or a failure.

In an interview on September 3, Rajan said the exercise might not have been a success after all.

Dealing with bad debts, Rajan said, it was not easy to convince banks to take the task head on. “The pillar where we made the least progress, despite the involvement of the best and the brightest in the RBI, was in getting the banks to recognise financial distress and deal with it.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)