Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was in India for a week and his visit became a talking point for the wrong reasons. While his choice of attire became a subject of social media derision, there were controversies about his government's dalliance with Canadian NRI groups that are antithetical to India's territorial integrity. In this Business Standard Special the writer looks at the controversies surrounding Trudeau's visit and tries to find whether there are any merits to the criticism in India.

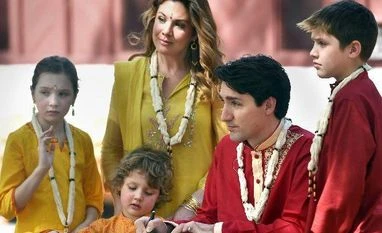

By all accounts, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s recently concluded visit to India was a disaster. Mired in the thorny politics of identity, memory, and symbolism, he cut a tragicomic figure, not least due to the numerous photos of his and his family’s specially tailored extravagant “Bollywood” wardrobe splashed all over the media.

Even before the trip was over, columnists in both countries concluded that Trudeau was receiving “a royal snub” from the Indian government. Prime Minister Modi did not welcome the Canadian first family at the airport in New Delhi, sending a junior minister of agriculture instead. Nor did Modi issue the customary welcome tweet that most heads of government receive upon their visit to India. He did not accompany Trudeau on the latter’s visit to Gujarat—a courtesy that has in the past been extended to Xi Jinping, Shinzo Abe, and Benjamin Netanyahu. Indeed, Modi and Trudeau did not meet until the sixth day of Trudeau’s eight-day visit, and that too for only half a day of consultations.

Critics back home alleged therefore that Trudeau’s visit lacked substance, that it ended up looking like “a series of photo opportunities,” “a costume parade masquerading as foreign policy.” Elsewhere, liberal and conservative watchers of Indian and Canadian politics alike excoriated the prime minister. India’s Barkha Dutt observed that he ended up “looking silly, diminished and desperate,” while the UK’s Stephen Daisley panned Trudeau’s “Captain Snowflake act” and labelled his wardrobe choices a “spectacle of well-meaning minstrelsy.”

Why did a globally celebrated superhero prime minister receive such shoddy treatment in India? And how did he get India so wrong? On the face of it, the main issue was his government’s pandering to members of its Sikh electorate who cling to the goal of creating Khalistan, an independent state for Sikhs carved out of Indian territory.

The Khalistan movement caused much bloodshed in northern India, especially Punjab, in the 1980s, including the deadliest terrorist attack originating on Canadian soil: the bombing of Air India Flight 182 (from Montreal to Delhi via London) in June 1985, which killed all 329 people on board. Although the movement finds few takers in Punjab today, the issue remains alive in left-wing and liberal politics in Canada, with politicians signalling their implicit and often explicit endorsement of the separatist ideology espoused by a non-trivial portion of Canada’s approximately 500,000 Sikhs, or 1.4% of the country’s total population.

This political dalliance has caused friction with India that has transcended party lines. Last year, Amarinder Singh, the chief minister of a Congress Party-led government in Punjab, refused to meet Canadian defence minister Harjit Sajjan, a Sikh who Singh alleged was a “Khalistani sympathiser.” Earlier this year, in response to the arrest of a British Sikh man in Punjab accused of the murders of several Hindu nationalist figures, Sikh religious organisations in Canada issued a ban on official visits to gurudwaras by Indian officials.

The coup de grâce to Trudeau’s visit thus occurred on February 22nd when it emerged that Jaspal Atwal, a former member of the terrorist outfit that carried out the Air India bombing who was also convicted for the attempted murder of a Punjab government minister in 1986, was photographed with Sophie Trudeau (the prime minister’s spouse) at an event in Mumbai the night before and had received an invitation (since rescinded) from the Canadian High Commissioner to a dinner reception for Trudeau in New Delhi. Although Atwal insisted he had no intention of attending the dinner and was in India on separate business, the incident was sufficient to kill any hopes of rescuing the Canadian premier’s already floundering visit.

It might seem convenient to dismiss these events as the result of political posturing and bureaucratic lapses, but at a deeper level Trudeau’s visit is a clear instance of the primacy of domestic politics over foreign policy, as well as the pitfalls of ignoring symbolism in politics. It would be naïve to assume that domestic politics do not shape foreign policy on both sides. Trudeau and Modi are both entering election years and face a simple calculation of domestic political benefits versus international costs when it comes to India-Canada relations, which are relatively insubstantial to begin with.

Trudeau faces the possibility of losing a sizeable portion of the Sikh vote to the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP) under Jagmeet Singh, who has taken openly supportive positions of the Khalistan movement in Canada. Modi for his part is committed to a more assertive foreign policy that brooks no challenges, real or imagined, to India’s national security and territorial integrity. Moreover, both Modi and Amarinder Singh are keenly aware, as Shekhar Gupta has noted, that the Khalistan movement is “a nightmare Punjabis want buried forever.”

It is also evident that Ottawa miscalculated the symbolic costs of its domestic politics, latching onto lehengas instead of the complexities of India’s evolving identity as a rising power, one that Modi himself wishes to make a “leading power” in global affairs. Trudeau’s misreading of Indian aspirations and priorities was evident when, on the eve of his visit, a former Indian High Commissioner to Canada described the prime minister from his time in Ottawa as someone who “used to attend almost every Indian function, and…used to make it a point to dress in ethnic wear.” Unsurprisingly, the invitation card issued by the Canadian High Commissioner to Jaspal Atwal and other guests required business attire or national dress, with “vibrant colours encouraged.”

Canadian Khalistanis pose no material threat to India today, yet this fact should not have blinded Ottawa to the symbolism of a foreign leader endorsing a cause that notionally threatens the territorial integrity of a postcolonial major power such as India. As the scholar Manjari Chatterjee Miller has shown, both India and China harbour a sense of victimhood in relation to their colonial experiences and consequently prioritize territorial sovereignty and status (or social standing) in their foreign relations. Any Japanese politician who has ignited Chinese nationalist passions by visiting the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo can testify to this fact.

The focus on territorial sovereignty was evident in the joint statement from Trudeau’s visit, which—unlike statements issued with the United States, for example—premised the bilateral relationship on “the fundamental principle of respect for sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity of the two countries,” and emphasized that “no country should allow its territory to be used for terrorist and violent extremist activities.” The focus on status was similarly evident in a senior BJP leader’s explanation that their party supported political rival Amarinder Singh’s stance on Trudeau’s politics because Modi “knows how to ensure that the prestige of the country isn’t compromised.”

Despite recent setbacks, however, Ottawa and Delhi can take comfort in the fact that the underlying foundation of their relations remains strong. Bilateral trade and investment are on the rise, a five-year agreement on Canadian uranium supplies was struck in 2015, and Canada remains a major source of remittances and tourism into India. In fact, virtually unmentioned in the media frenzy over the failures of Trudeau’s visit were his meetings with numerous heads of Indian industry and civil society in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab. Given the increasingly active role of Indian states in India’s external economic relations, these meetings alone promise to keep the India-Canada relationship afloat despite the occasional squall caused by domestic politics and tone-deaf diplomacy.

Rohan Mukherjee is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Yale-NUS College, Singapore

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)