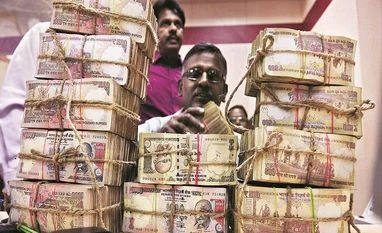

Demonetisation caused a 2-3 percentage-point reduction in jobs and economic activity, new research has found, and a similar contraction in bank credit vis-a-vis the normal course of activity, in the two months after the note ban was announced on November 8, 2016.

This is the first research on demonetisation in which the impact was studied across India’s districts (sub-national level), and the effect mapped on to the national level. Till now, only national level effects were studied, which underestimated the impact, the economists noted in the study.

“Cash shortage caused by demonetisation generated a decline in national economic activity of roughly 3 percentage points or more in November and December 2016. (The) effect on bank credit implies a 2 percentage points or more decline in October-December 2016,” it noted.

The cash shortfall affected demand in the shorter term, it noted. The study found “powerful evidence” of a link between money and output during demonetisation, and rejected the notion that demonetisation did not affect real economic activity.

Gita Gopinath, chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Prachi Mishra of Goldman Sachs (formerly Reserve Bank of India), Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard University, and Abhinav Narayanan of the RBI have authored the paper published in National Bureau of Economic Research, USA (https://www.nber.org/papers/w25370).

In a first, the researchers used district-level data on the following indicators: Prevalence of old demonetised notes and their replacement by new notes, employment, district-wise night-light intensity, gross domestic product, and credit/deposit in banks.

They also used transactions using cards (debit or credit) as point-of-sale (PoS) terminals in nearly 600 districts, and transactions clocked in the database of a popular e-wallet company across the same districts.

N Bhanumurthy, professor of economics at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, said this was an innovative way to understand the differential impact of demonetisation on various regions in the country.

“The initial conditions such as cash availability in various denominations across different districts mattered when it came to impact on the economy in those districts,” he said.

Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, urban regions of Gujarat and Maharashtra, and parts of peninsular southern states were the most affected regions, a map provided in the research paper suggested.

The paper also said the “impact of the cash shortage points to an absolute decline in economic activity at the end of 2016 not captured in official statistics”.

But it also said demonetisation might have long-term benefits that arise from improvement in tax collection, a shift to savings in financial instruments, and non-cash payment mechanisms.

S Mahendra Dev, director at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, said this research corroborated what was visible in the immediate aftermath of demonetisation.

“This is the first study on a desegregated impact of demonetisation, and it confirms the anecdotal findings with statistical results. It could further explain the sustained impact on farm prices (agriculture sector) and small enterprises,” he said.

It said areas with stronger currency shocks experienced sharper declines in ATM withdrawals. Economic activity in these areas fell sharply compared to districts where the shock was milder. Deposits increased, while credit fell quicker in districts with a strong shock, and the public took up new payment modes faster than in other regions.

It defined “stronger shock” as one where a higher proportion of the currency was made invalid on November 8, 2016, and a “weaker shock” where the proportion of demonetised currency was relatively low.

The team used the district-level data to find the difference between the impact experienced by individuals and businesses in the most affected districts and the least affected districts.

The difference in contraction in economic activity and employment between the most affected and the least affected districts was 4 percentage points, it found. The difference in contraction in night-light intensity among the two was as big as 14 percentage points, it noted.

On credit demand, it said while the effect on deposits appeared short-lived, that on credit was more persistent over the subsequent quarters due to lower borrower demand. Here too, it indicated that demonetisation hampered demand.

Using the RBI data on cash movement in currency chests, it found that the arrival rate of new currency notes varied across areas, and used it as the basis for research. It also noted households switched to non-cash forms of payment to attenuate the impact of the cash shortage.

“Any mechanism that creates a record of transactions (‘memory’) can substitute for money in a new monetarist economy,” it said.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)