In a television interview earlier this month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi categorically rejected the possibility of a nationwide farm loan waiver in the run up to the general elections.

The debate on whether a loan waiver is the right way to alleviate farm distress, or whether cash support is a better and more enduring solution will go on. But it is worth revisiting the after-effects of the second nationwide farm loan waiver scheme implemented in India in 2008.

A lopsided scheme?

Firstly, a recent survey by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard) shows that loan waivers benefitted only 30 per cent of the farmers in India in 2016-17.

Secondly, it is the bigger land owners who are likely to benefit more from any waiver, if the scheme is not limited to small and marginal farmers; the reason for this is that their level of indebtedness is twice that of small farmers.

Thirdly, while the gap between the income levels and debt outstanding of big farmers is much smaller than that of small farmers, whose income levels are just a fraction of their loans.

Finally, the report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) on the farm loan waiver implemented by the erstwhile United Progressive Alliance government shows that a substantial proportion of beneficiaries faced lapses in the form of no benefit or reduced benefit. Further, a host of irregularities were reported in its implementation due to a multiplicity of stakeholders and the limited use of technology.

Waiver math

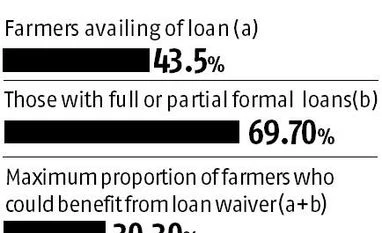

The Nabard survey said that about 43.5 per cent of farmers availed loans in their reference period. Of them, about 69.7 per cent completely or partially relied on banks and other institutional sources for financial assistance. This means that only 30 per cent of all farmers in the country actually take loans from banks.

Under such circumstances, a waiver of the outstanding dues of farmers payable to banks, would benefit less than third of the country's cultivators.

The indebtedness and loan taking ability across decile classes of income is striking. A decile is a tenth portion of a group, and monthly per capita expenditure has been used as an indicator of income.

In the richest decile (roughly farmers who form the top 10 per cent of spenders), about 68 per cent of farmer households were indebted in 2016-17. In the same group, about 61 per cent had availed fresh finance from banks and informal sources put together.

In the poorest decile (roughly farmers who form the bottom 10 per cent of spenders), about 40 per cent are indebted, and less than a third, or 32 per cent, had availed fresh loans.

Across the ten deciles, annual incomes of the poorest are way less than the average debt held by the households. For example, in the poorest decile, average outstanding farm debt is at least six times the annual income. In the richest decile, the annual income is 1.5 times the outstanding debt.

Further, the outstanding debt in the 2nd to the 7th decile is less than the outstanding debt held by the poorest decile. This means that wealthier the farmers are better off by a huge margin than the poorest of them.

Now, let us look at how the 2008 debt waiver by the UPA, or the Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief scheme, turned out. As against the intended beneficiary count of 42.9 million farmers, the scheme at its closure could benefit 80 per cent of them, or about 34.5 million.

The CAG surveyed some 90,000 farmers—about 10 per cent of whom were non-beneficiaries—after the complete implementation of the scheme. More than 700 bank branches in 92 districts in the country were surveyed.

A third of the farmers did not get any financial acknowledgement of the waived debt. This is crucial since the proof of issue certificate is mandatory for farmers to get fresh loans in the subsequent farming seasons.

Bihar and Andhra Pradesh had the highest proportion of such cases, the CAG report said. Business Standard had earlier reported on how credit disbursal falls in immediate years after loan waiver implementation in states.

More than a fifth of cases in the audit had serious lapses or errors of some or the other kind, with many overlaps of the following kinds.

On the one hand, about 13.5 per cent of the accounts not deemed eligible were found to be actually eligible, but for some reason banks did not certify them as beneficiaries. Bulk of these accounts were farmers from Madhya Pradesh.

On the other, of those who benefitted from the scheme, about 8.5 per cent were actually ineligible for debt relief. Madhya Pradesh got its name etched in this category well, with about a fourth of such cases in the state. Karnataka had the highest proportion of such cases in the CAG audit.

The newly elected Madhya Pradesh government has notified a farm debt waiver scheme in the state.

Of those eligible, there was a mismatch to some extent with regard to the amount to be waived. About 4 per cent of the farmers’ accounts received undue benefits, while 2 per cent received less money than they were entitled to.

In six per cent of the cases, banks claimed interest charges from the scheme which were not borne by the indebted farmers in the first place. This happened since the DFS did not have bank and branch-wise details on the interest payment eligible to banks.

The national auditor pointed out that the department of financial services in the finance ministry, which was the leading implementer of the scheme was unable to monitor the implementation that panned over four years. This issue seems to have been resolved to some extent due to better availability and computerisation of data and records, say bankers and state officials who are currently implementing the scheme.

Banks were given a paltry window of 35 days to finalise the list of beneficiaries which totaled 4.29 million in the final count. This was a major reason for most of the irregularities that ensued later, the CAG report said. The final tally of beneficiaries was 34.5 million.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)