The state is facing the worst drought in 140 years. Water resources are becoming depleted, taking a toll on the livelihood of farmers, which is leading to suicides. T E Narasimhan and Gireesh Babu report from the drought-hit districts of Thanjavur, Tiruvarur, Nagapattinam, Tiruvallur and Kancheepuram

Azhagesan, 36, had been under stress for several days because his paddy field, a piece of leased land in a small village in Tiruvarur district, withered owing to the scorching sun, deficient rain, and dried-up water resources. He was found dead in his field, leaving his three children and their mother in the lurch.

Arogyamary, the mother, is one among hundreds of such widows in the Cauvery delta, which consists of 12 districts with around 1.6 million acres (one acre is 43,560 square feet) of agricultural land, and is mostly an agrarian region.

The government has compensated the families of 82 such deceased farmers, including Azhagesan, says a farmers’ association. It has sanctioned Rs 3 lakh for their families. However, the number of deaths due to this calamitous situation is around 300, including suicides and those due to heart attacks, the causes of which are failing crops and increasing debt.

This is the first time that both the monsoons have failed in the same year, leaving the farmers traumatised.

Till recently, Thanjavur had no record of suicides by farmers even if there was a drop in the production of one or two crops. But in the past few months, 18 farmers have died, and six of them have committed suicide, claims Sami Natarajan, Thanjavur district secretary, Tamil Nadu Farmers’ Association.

For many of them, the last Kuruvai (short crop during June-September) and Samba (the crop during October-January) wilted due to monsoon failure and lack of surface water from the Cauvery. Many who raised the crop abandoned cultivation halfway and used it as cattle fodder since they could not find the water to irrigate the fields, says Arogyamary, a farmer-turned-daily wage worker in Thanjavur.

Farmers who used to cultivate rice in Tamil Nadu and other states have to stand in front of ration shops to get one or two kilos for their own consumption. Agrees Thavamani, who is finding it hard to repay debts, including loans taken against gold.

Sethurajan, a small farmer, says that the crop now depends on groundwater, drawn from borewells 500-600 feet deep, and at any time the crop might turn bad if the well dries up or throws out sand, damaging the motor pumps. Digging a well requires at least Rs 1 lakh, and the cost could go above Rs 3 lakh if the depth of the well is 500 feet.

Farmers in the delta region are buying water for irrigation or deploying gensets because the power generated by transformers fails to provide the energy to run the high-powered motors. Many of them have run up huge debts and are not aware what to do, considering that jobs are shrinking and banks are reluctant to give further loans.

The cost of cultivating an acre of paddy is around Rs 30,000. If a farmer gets a good harvest and a good price, it could fetch him or her Rs 60,000 per acre.

Many in the Thanjavur belt are raising a summer crop using groundwater and this could jeopardise the daily life of the people in the region, says S Ranganathan, secretary of the Cauvery Delta Farmers Welfare Association. Groundwater is the major source of drinking water, while agriculture is expected to rely on surface water.

The additional crop during the summer is a recent trend that started after the region received adequate rain in the past and the water was surplus. However, some farmers are using groundwater for this.

The summer crop is expected to make good the losses on account of the Kuruvai and Samba crops, says Natarajan. The summer crop does not need pesticides or other cares and would give a greater yield, he says.

During the Samba season last year, Karnataka supplied water from September 24 but stopped it by November 20, which affected the crop.

Besides the monsoon, demonetisation and prices also hurt farmers. Demonetisation has affected those who required money to manage their fields in the crucial months of November and December, during the last Samba season, Ranganathan said.

Natarajan says farmers would require at least Rs 2,200 per quintal of rice, while they are getting Rs 1,510 per quintal. The pending amount to be received from various sugar mills is around Rs 600 crore. Small farmers are the first to be hit by any disaster, considering there is no support for them. Those who turned to daily wages for livelihood also suffered because the MGNREGS failed to offer adequate work throughout the days, a daily wage worker says.

The Cauvery is the key source of water in the delta region, which has many dams, lakes, and other water bodies, including the more than 2,000-year-old Grand Anicut. But most of them have dried up.

The Cauvery basin, in central Tamil Nadu, spans 81,155 square km. Of the state’s 16,682 villages, 13,305 were drought-affected in January, according to the state government data. The storage of water in the six major reservoirs in the state was just 6.2 per cent of capacity as of April 27, 2017.

They said hardly 20 per cent of the crop has been grown and that too by people who can afford to invest in borewells. Tamil Nadu is likely produce 600,000 tonnes in the 2017-18 season, down from around 1 million tonnes.

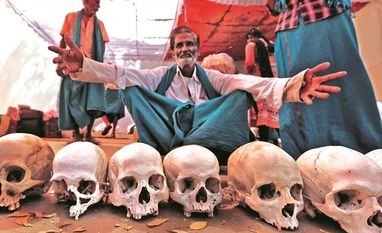

Farmers are asking the Centre and the state government to waive loans, address the Cauvery dispute, and lend more for digging borewells. They went to Delhi and sat for nearly 40 days in Jantar Mantar with skulls of farmers who committed suicide, ate rats, and consumed urine instead of water but the central government seems to have no time to meet or hear them. Rather, the Bharatiya Janata Party blamed the state government for the crisis and said it was a state subject.

Much to the surprise of the farmers, the state government in an affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court on Friday said that 30 farmers committed suicide because of “various causes and family issues” while the rest of the farmers died out of cardiac arrest and other illness.

The water quest

With the reservoirs and dams drying up, the state, including Chennai, is facing a huge drinking-water crisis. The storage in the four water reservoirs under the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board was just 836 mcft (million cubic feet) out of the total capacity of 11,057 mcft, as on April 27. The storage level was 5,741 mcft during the same day of 2016.

Cholavaram, a reservoir, with a full capacity of 881 mcft, has no water now.

Tankers carrying water to commercial establishments, schools, colleges, factories, poultry farms, and office establishments have become a regular scene now. A tanker of water available in villages for Rs 300-400 fetches up to Rs 3,000-3,500. Many have got together to dig borewells, which is aggravating the situation.

People are lining up with plastic pots for hours in front of a tap or a tanker truck for drinking water. Sometimes there is no water supply for days on end, resulting in chaos on roads or in front of district administration offices.

On the other side, the water mafia is charging Rs 2,500-3,000 for a tanker, which supplies 4,000-6,000 litres.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)