Nitin Tyagi is a young farmer in Budhagaon village of Baghpat district of Uttar Pradesh.

A few years ago, Tyagi left his fairly lucrative job in the medical industry and shifted base to his ancestral village to look after his land and property.

He opened a small shop selling farm inputs in the village and also started taking a greater interest in agricultural matters which had so far been looked after by his father and uncles.

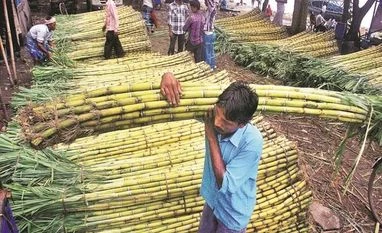

Tyagi and his brothers primarily grow sugarcane, potato and wheat on nearly 10 acres of land with sugarcane taking up most of his time and effort.

Being one of the most important and lucrative cash crops of the region, sugarcane is directly linked to the fate of millions of farmers in west UP and with it, the electoral fortunes of political parties seeking their votes in the coming assembly polls.

With the farm laws out of the way, the focus of several commentators and sector watchers has shifted to the other large problems in the farm sector in poll-bound UP.

For Tyagi and his middle-aged uncle Satbeer, the protest against the farm laws and the anger it generated in western UP was a manifestation of a larger problem impacting the sector, of which low price of sugarcane, the delay in payment and the recent shortage of DAP are the most visible.

“I have not been a big supporter of the farmers’ movement as it was largely people from a particular caste who were at the forefront. But the issue raised by them definitely resonated irrespective of one’s political affiliation,” Tyagi candidly admitted when this reporter visited him barely days before the three controversial laws were repealed.

Sugarcane and the economics surrounding it, according to some estimates, have a bearing on 100-odd assembly seats in west UP out of the total 403 seats.

Any let-up in this space could have a serious impact on any political party’s chances of forming the government in Lucknow.

“Our cost of production has risen manifold over the past few years, but the state-advised price of sugarcane has not risen proportionately,” Tyagi laments.

Of late, the UP government announced a Rs 25-per-quintal hike in the state advised price (SAP) or purchase price of the crop for the 2021-22 season that commenced on October 1.

The hike, which was among the highest in the tenure of the BJP government in UP, has not been able to assuage a large section of farmers who have been demanding a sugarcane SAP in excess of Rs 425 per quintal due to increase in diesel rates and other production costs, and also because purchase prices haven’t been raised for the past three years.

“The meagre Rs 25-per-quintal hike is a big joke by the UP government on the farmers, as prices in neighbouring states are more than Rs 360 per quintal, while electricity rates are also higher in UP. In fact, BJP’s own Member of Parliament, Varun Gandhi has demanded a price of Rs 400 per quintal for sugarcane,” Dharmendra Malik, spokesperson of Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU), one of the main groups spearheading the farmers’ agitation, had said in a statement then.

“Instead of announcing a big hike after four years, the government should have hiked the SAP instead, by minimum Rs 5 per quintal every year. Had it done so, we would not have lost a sizable chunk of our earnings,” Rampal Singh, another farmer from the neighbouring Sakrod village said.

Tyagi has other complaints as well.

He said the nearest sugar mills--two in the cooperative sector and one managed by a private firm--do not run on a regular basis and sometimes he has to wait for days before he can deliver his crop.

“We were promised sugarcane dues would be cleared within the mandatory 14 days, but though things are better now, we are still waiting for the payment,” Tyagi complains.

He said though procurement of other crops like wheat has improved too, a great deal of difficulty is still created by lower level officials in ensuring that genuine farmers get the benefit of the process.

Meanwhile, as far as sugarcane is concerned, the state government have claimed that in the last three sugarcane seasons (2017-18 to 2019-20) almost 100 per cent payments accruing to farmers and a sum of around Rs 1.45 trillion has been transferred by way of sugarcane payment.

In the 2020-21 sugar season that ended in September too, almost 90 per cent of sugarcane dues were cleared by August end.

That apart, the government claims to have re-started several closed sugar mills and expanded the crushing capacities of a few others to help sugarcane farmers.

Rising cost of sugarcane production

One big grudge of several farmers of West UP have is that though the cost of sugarcane production has risen manifold the past few years, returns have not been commensurate.

In areas surrounding Baghpat, according to agriculture scientists, the per-hectare cost of producing cane has gone up from Rs 70,000-72,000 to about Rs 94,000, while the average yield in the area in 2021-22 season is projected to be 700-750 quintals per hectare.

This translates into an average earning of around Rs 2,27,500-2,44,000 per hectare. Thus the total earning from sugarcane in a year comes to Rs 1,33,500-1,50,000 per hectare.

“The average land holding in most parts of the region surrounding Baghpat is less than one hectare, so this income drops further. Also, one needs to remember that this is expected earning of Rs 133,500-150,000 per hectare is annual because sugarcane is a 10 months’ crop and the returns come only once in a year,” a senior agriculture scientist said. "Therefore, to say that returns from sugarcane have been commensurate after the recent increase in SAP is slightly exaggerated."

He said sugarcane yields in the region in the 2021-22 season that started in October are expected to lower at about 700 quintals per hectare as compared to 850-900 quintals in 2020-21 due to repeated pest attack on the standing crop.

Farmers complain that the cost of labour has seen one of the biggest increases the past few years due to acute shortage.

“Till a few years back, the labour charge for working in sugarcane fields was Rs 1,250-1,300 per acre, This has now gone up to Rs 1,800-2,000 per acre. You need labour two times in a single sugarcane season for tying the cane and for other purposes,” Devender Singh, another local farmer who also dabbled in modern farming techniques.

But despite all the hardships, sugarcane cultivation in UP has only grown during the past few years, driven by better crop varieties and high recovery rates.

Higher returns and better recovery

One big reason why farmers in UP have been opting for sugarcane year after year despite facing a host of challenges is its assured price vis-à-vis other competing crops.

Data from Commission for Agriculture Costs and Prices (CACP), the main price-fixing body of the government, shows that between 2015-16 and 2017-18, sugarcane gave 100 per cent more return than its cost of production (A2+FL cost), while a combination of cotton and wheat gave 50 per cent more return, and the paddy-and-wheat combination returned 47 per cent over the production cost.

The following cropping patterns gave returns in the 28-37 per cent range over estimated cost of production: soybean-plus-wheat, only paddy, soybean-plus-gram.

In contrast, a single sugarcane crop gave a much better return to the average farmer over his cost of production as compared to any other combination of two crops.

In UP, another factor is the emergence of new cane varieties, largely Co-0238, which has improved recovery rates.

Data shows that sugar recovery in Uttar Pradesh, which lingered at 9-9.5 per cent till 2014-15 sugar season, saw a quantum jump from 2015-16 and has thereafter maintained the rising trend.

In the 2019-20 sugar season, the state recorded a recovery rate of 11.26 per cent, or 18.52 per cent more than the recovery rate of 2014-15 season.

Recovery rate is the quantum of sugar derived after processing a definite weight of sugarcane.

The higher the recovery rate, the higher will be the sugar produced from each stick of cane.

This quantum jump in the sugar recovery rate in UP immediately impacted production, and from about 5.8 million tonnes in 2009-10, UP’s sugar production jumped to 12.6 million tonnes in the 2019-20 sugar season, up 37 per cent in a span of 10 years.

In contrast, sugar recovery in Maharashtra, the country’s next most important sugarcane producing state, has hovered at 11.2-11.5 per cent between 2009-10 and 2019-20, and production too fluctuated between 7.5 million tonnes and 11 million tonnes during this period.

“Above all, sugarcane is a much sturdier crop and in the worst of times, if somebody is desperately in need of money, he can sell the cane to the local jaggery unit (called kolhu) for Rs 200-250 per quintal without waiting for the mills to start. No other crop can give this kind of return,” Nitin Tyagi sums up pointing towards the burning fumes from the kolhu adjoining his field.

The writer visited Baghpat in Western Uttar Pradesh to gather inputs for this story

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)