Come June 1, farmers in many parts of the country are planning to stop supplies of essential items like milk, vegetables and fruit in cities in protest against plummeting farm-gate prices — a phenomenon that has been a recurrent occurrence through the four years of the Narendra Modi government.

The images of the long march of Maharashtra farmers to Mumbai earlier this year, widespread protests in Madhya Pradesh owing to depressed prices after the announcement of the price deficiency payment scheme, and farmers of Tamil Nadu agitating in Delhi come to mind when one thinks of agriculture in India now.

Back-to-back drought in 2014 and 2015 and a slump in realisations have brought agriculture at the forefront of policymaking, with the Centre announcing a slew of measures, including a promised price which would be 50 per cent more than the cost of production.

It has set a target of doubling the real income of farmers by 2022, an ambitious goal, given that farm growth in the four years of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government has been below 4 per cent.

In the four years of the Modi government, record production has been achieved twice, insurance coverage has jumped, a national online portal for marketing farm produce marketing has been developed, and farmers of two big states have got partial relief from debts.

But at the same time, surplus production has pushed down wholesale prices, affecting farmers’ incomes directly.

Insurance claims under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) have been either delayed or unpaid to a substantial extent, the government’s own panel demonstrated last month.

The volume of farm produce traded online has not crossed 1 per cent of traded agricultural produce in the country. But more importantly, wages of farm labourers have been stagnant for three years.

Prices of major agricultural commodities have been depressed while investments in the farm sector have been the lowest since 2005.

“The terms of trade in agriculture, in other words the difference between prices received by farmers and prices paid by them, have turned unfavourable in the past three-four years while growth rates have also dropped. Though efforts like electronic markets are a step in the right direction, in the absence of proper price signals they haven’t made a mark,” Yogendra Alagh, a former union minister and chairman of the Institute of Rural Management, Anand, told Business Standard.

He said issues like easing marketing bottlenecks were being brushed aside under the garb of slogans like “doubling farmers’ income” by 2022, which is simply unattainable.

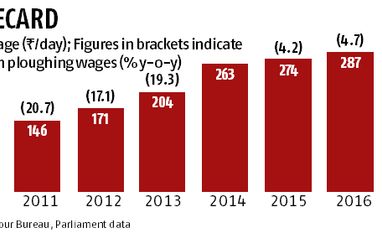

According to the representative data, farm wages have been stagnant in the past three years, compared to real growth (taking inflation into account) in the preceding three years.

Nominal wages of ploughing workers (the category for which the data is available uniformly) grew by more than 15 per cent in years before the BJP came to power in 2014.

Factoring in high levels of inflation in that reference period, wages still grew by at least 5 per cent for three years, 2011-13.

On the contrary, nominal farm wages for ploughing workers grew 4-6 per cent under the NDA government, in a period when inflation too was stable in a range of 4-5 per cent, going below 2 per cent for a very brief period in 2017.

A recent Reserve Bank of India (RBI) occasional paper by Sujata Kundu showed that average growth in real agricultural wages has been lower after 2014 than in the decade preceding it.

Prices in representative mandis for three selected crops were depressed on more occasions and with a higher degree under the NDA government than in previous years.

Prices of soya bean declined thrice in the last four years in Indore. The case was similar for cotton in Yavatmal, Maharashtra. In the case of tur (arhar or pigeon pea), prices remained depressed for two consecutive years after a disruptive doubling of wholesale prices owing to an unprecedented drop in production.

“Though the intention of the government is good, the policies churned out were not implementable and that’s a reason why farmers aren’t satisfied with the government,” Ajay Vir Jakhar, chairman of the Bharat Krishak Samaj and the Punjab Farmers Commission, told Business Standard.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)