The goods and services tax (GST), a much-awaited and crucial reform, finally got implemented on July 1. It aims to provide a simplified single regime, in line with the framework applicable in at least 140 nations. We look at how the new regime will hit the pocket of different income groups.

The new system offers a four-tier rate structure for both goods and services, based on the principle of ‘equivalence’. Efforts have been made to ensure different economic classes are not subject to tax at the same rate. Barring a couple of special cases, there are not many products or services where the rates have moved either upwards or downwards radically, compared to the aggregate tax incidence under the earlier regime. For instance, most services, previously subject to 15 per cent service tax, now have to pay a GST of 18 per cent. Though the rate of tax on services has gone up by three percentage points, the increased bracket of credits to a service sector will help companies reduce their transaction cost. Hence, the overall burden on peoples’ pocket is expected to go down. Altogether, GST is a blended pack, with many necessities becoming cheaper, while some other products could get somewhat more costly.

Households earning more than Rs 50 lakh annually: GST will impact luxuries like staying in five-star hotels, travelling in business class, eating out, etc. To begin, let’s examine the impact on eating at a good restaurant, with facilities such as air conditioning and liquor licence. On account of removal of cascading taxes and simplification of the mechanism, the effective rate has fallen to 18 per cent from the erstwhile ones which could range up to 20 per cent. Something similar has happened to ownership of luxury cars. Despite imposition of a cess over and above the basic GST, the effective rate on high-end cars has reduced from a maximum of 45 per cent to 43 per cent.

The tax mechanism for hotel stays has also been streamlined. Luxury hotels having rates above Rs 7,500 will attract GST at 28 per cent, keeping their cost to the end customer more or less the same. The GST rate on business class tickets has been pegged at 12 per cent, against the earlier service rate of 8.4 per cent, an increase in travel costs. Buying a new house under the regime is going to cost slightly more in the short run. For under-construction properties, the earlier rate was broadly around six per cent in most states (other than a few where the VAT rate was higher), comprising service tax and value added tax (VAT). Under GST, the rate has been increased to 12 per cent.

Households with annual income of Rs 20-50 lakh: To analyse the impact of GST on households having a moderate income, let us leave aside the luxuries discussed above and focus on daily expenses, including daily necessities, transportation, etc. As the rates have been determined on the principle of equivalence, the overall impact on the majority of items this income category consumes has been largely positive. For instance, cooking food at home has become relatively cheaper with reduction in rates on essential items. Most food items such as sugar, tea, edible oil, foodgrain, etc, have been kept at a lower rate of 5 per cent. The rate on restaurants without air-conditioning or liquor licences has been pegged at 12 per cent. This is a welcome change, as the cascading of taxes on this sector under the previous regime has been done away with.

Travel by radio taxis has become slightly cheaper, with the rate coming down to 5 per cent, as against the service tax of 6 per cent earlier. Owning a mid-segment car will also be less expensive by 2-4 per cent.

Staying at a mid-range hotel will be less costly, as the new tax regime has made mid-tier ones marginally more economical. Taxability under the earlier regime was complex. Three taxes applied to hotel stay, namely service tax (effective rate of 9 per cent), luxury tax (effective rate of 5-15 per cent, depending upon the state) and VAT at a residual rate of 12.50-15 per cent (depending on the state). Now, a single tax will be charged and the rate will depend on the published room rate of the hotel. For instance, there will be no GST on hotel rates of less than Rs 1,000; those above Rs 1,000 and up to Rs 2,500 will attract GST at 12 per cent; and rates above Rs 2,500 and up to Rs 7,500 will attract GST at 18 per cent.

Passengers flying in economy class will also heave a sigh of relief, as the effective rate on flight tickets has been marginally reduced from

5.6 per cent service tax to five per cent GST. Households with annual income less than Rs 20 lakh: GST has brought some relief for this segment as well with the tax impact on necessities such as essential items of daily consumption, stay in rented accommodation, etc, more or less neutral. Most food items have been kept in the tax bracket of 5 per cent. Essential items such as milk, curd, cereals, rice (unbranded), etc, have been exempted from GST altogether. The impact on transportation cost will be largely neutral, as no GST has been levied on travel by central or state run transport facilities, metrorail or monorail services, and metered cabs, which were exempt under the earlier regime as well. Also, there has been no change in the treatment of renting out property for residential purposes. Hence, the budget of the consumer will not be affected.

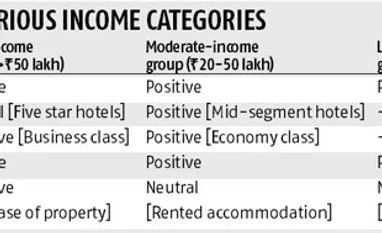

To summarise, in some cases the tax rates have gone up and in others they have remained unchanged or even fallen (see table which offers a summary).

By the experience of GST in other countries, it could result in an initial inflationary impact. To ensure businesses does not increase prices in the short run even if the tax rates are marginally higher, the government has put in place an anti-profiteering clause in the law which mandates that suppliers pass on all the benefits received by way of reduced prices. It remains to be seen how well the government manages to deliver on its promise of holistic economic growth and reduced inflation in the long run, courtesy the ‘one nation, one tax’ regime.

The author is partner–indirect tax with PwC India. Kishore Kumar, director, and Vidushi Gupta, assistant manager–indirect tax, PwC India also contributed to this article.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)