The Modi government’s radical economic policies of demonetisation and the goods and services tax (GST) have had a profound and debilitating impact on the agrarian fabric of the country. While the note ban has broken the back of the rural economy, the GST has exacerbated the predicament of the rural artisans. Though the implications of GST for traders in the urban economy are being discussed extensively, its impact on the weaker and marginalised sections of the rural economy has been largely ignored. For decades, millions of rural artisans have been making ends meet through their traditional skills with hardly any help from the government. With the imposition of GST, their livelihood and survival has come into question.

In order to highlight the inequity of this measure, the handloom activist and theatre director Prasanna had taken up a hunger strike in Bengaluru on October 14 to demand a comprehensive withdrawal of GST on handmade goods marketed by rural cooperatives. Even as Prasanna broke his fast on the evening of October 19 following an “assurance” from Karnataka chief minister that the state government would support the demand for no GST on handmade products, he made it clear that the campaign was by no means over.

Handmade products are now being taxed for the first time since independence, and the inputs cost more. As a result, handmade goods have become even more expensive and the struggling industries have been severely impacted. Although the government has exempted those manufacturing handmade products with a turnover of less than 2 million from GST, such a taxation system discriminates against rural cooperatives marketing these products and eventually burdens the artisan.

While the imposition of GST on handmade goods is bound to have a severe impact on the sector, it is but the newest measure in a long chain of government policies which neglect and discriminate against rural artisans.

Past policies

The handloom sector — the most important rural artisanal industry — supports the livelihood of millions of weavers as well as other allied workers. According to the latest handloom census of 2009-10, nearly 2.7 million households across the country are engaged in weaving and supporting activities, though experts believe that this figure is a gross underestimate.

It is well understood that colonialism dealt a devastating blow to India’s traditional handloom industry leading to the immiseration of the countryside. Following the industrial revolution and in the colonial period, the economic condition of India’s handloom weavers suffered a marked decline. Among the several complex factors which contributed to the decline of this industry, protectionist policies which favoured industrial British textiles and imposed heavy duties on Indian ones played a dominant role. It was only apt that Mahatma Gandhi chose khadi — handspun and handwoven cloth — as his radical tool to rescue India from the grip of foreign cloth and rule.

However, with the arrival of independence, this legacy of the freedom movement was no protection for the handloom sector in an India industrialising itself in the manner of the West. Successive governments discriminated against and neglected the handloom sector to favour mills and mechanised powerlooms. Though handloom was glorified in every government policy and report on the textile sector, any concession towards it remained only on paper. The phenomenal growth of powerlooms fully supported by the government edged the handloom sector out. Unable to compete with powerloom workers churning out cheap imitations of handloom products by the hour, the handloom weaver was left entirely in the lurch.

In the early phase of liberalisation in India, 1985 was a crucial year in the textile history of the country due to the promulgation of the New Textile Policy.

Reviewing the policy in Economic and Political Weekly, K Srinivasulu, underscored that for the first time since independence, the policy emphasised productivity in sharp contrast to employment. Further, the hitherto sectoral differentiation of the textile industry in the handloom, powerloom and mill sectors was replaced by a process-oriented view with spinning, weaving and product-processing as the key processes. As a result, the specific needs of the handloom sector were ignored, existing restrictions on mills and powerlooms were removed and the three sectors were pitted against one another as equal competitors — the ultimate injustice to the handloom weaver.

The measures in this policy supposedly intended to protect handlooms worked to the advantage of the illegal proliferation of powerlooms. With every job created in the powerloom sector displacing 14 handloom weavers, the 1985 textile policy spelt nothing but doom for the handloom sector.

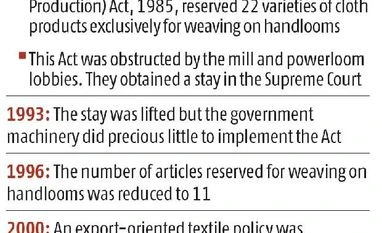

Despite this broader neglect, the government had provided marginal support for handloom weavers by way of a few protectionist measures in the years after independence, one of which was to reserve certain cloth products for the decentralised handloom sector. In continuation of this approach, the Handlooms (Reservation of Articles for Production) Act of 1985 reserved 22 varieties of cloth products exclusively for weaving on handlooms. This Act was obstructed by the powerful mill and powerloom lobbies which obtained a stay in the Supreme Court. But even after the stay was lifted in 1993, the government machinery did precious little to implement the Act. As a result, the powerloom sector was given a free hand to sell fake imitations of handloom products. Further along, in 1996, the number of articles reserved for weaving on handlooms was reduced to 11.

That the export-oriented textile policy promulgated in the year 2000 liberalised controls and regulations while paying lip service to the handloom sector should then come as no surprise. Going forward, in 2012, the government attempted to change the definition of a handloom itself to enable the powerloom industry to poach on the benefits intended for the handloom weaver.

Thus, it is obvious that bringing the handmade goods sector within the ambit of GST is just another iteration of the policy bias against the artisan, the responsibility for which should be shared by all political parties that have ruled the country. The texture of the rural landscape today is one of profound distress – with the neglect of the agrarian economy and the perpetual injustice meted out to producers. Though there has been a limited discourse on the distress of the Indian farmer in recent months, the troubles of the handmade goods sector deserve no less attention. If the government cannot help artisans, the least it can do is not add to their burden. The handloom activist Prasanna deserves our gratitude for drawing attention to this important issue and rendering a service to India’s artisanal communities.

By arrangement with the wire.in

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)