Inflows from foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) continue unabated into the debt market despite a risk of lower earning, owing to the narrowing spread between developed country papers and Indian government bonds.

While all emerging markets (EMs), particularly those in Asia, continue to attract huge capital flows, the Indian one stands out. According to financial services entity Nomura, in the June quarter, India recorded its highest ever quarterly debt inflow, both in the government bonds and corporate bonds segments.

Total inflow in Indian debt has been Rs 63,490 crore, of which Indian government bonds have inflow of Rs 42,760 crore. On a year-to-date (YTD) basis, as on end-June, the inflow has been Rs 94,800 crore, the highest on record. Central government bonds have received inflow of Rs 61,670 crore in this period. Corporate debt — which has had inflow in every month this calendar year — has seen YTD inflow of Rs 32,500 crore. State development loans in the period have got Rs 650 crore.

A number of factors work in favour of foreign investors. From their perspective, India’s currency and fixed income macro economic fundamentals look attractive.

Oil prices have stayed low, inflation is under control, reforms (goods and services tax (GST), Bankruptcy Code), have continued, and prospects for political stability have improved after the Uttar Pradesh poll results.

And, there is continued global savings and liquidity, which continues to move towards EMs. “This wall of continued liquidity has supported risk assets — including EM assets — despite all the geopolitical events and populism. And, within EMs, India's macros stand out a fair bit,” said Ananth Narayan, head of financial markets for Southeast and South Asia, Standard Chartered Bank.

Rates, rupee

A big clincher is India’s positive real interest rate, the difference between the nominal rate and inflation. “In a relative sense, real interest rates in India are still seen on the higher side, compared to the rest of the world. This has resulted in FPI money coming in, both in equity and debt,” said Narayan.

The 10-year government bond yield is now at 6.5 per cent, whereas retail inflation in June recorded an all-time low of 1.54 per cent. Therefore, the real interest rate works out to about a full five percentage points. This is huge from a return perspective. The resolve to keep retail inflation at 4 per cent by the Reserve Bank of India means real rates could remain positive for the foreseeable future.

Add the rupee’s stability. And, the thinking in some parts of the government that a stronger rupee is a reflection of the country’s strength. It also indicates that the government and the central bank might want to see the rupee maintaining its relative strength over other currencies in the region. A strong and stable rupee helps foreign investors and, in fact, some of the flows have been a pure bet on rupee stability, say bond market observers.

India also packs other punches compared with EM peers. Arvind Narayanan, head of treasury at DBS India, said high economic growth and growing foreign exchange reserves give additional comfort to global investors.

“Fundamental reforms like GST, the Bankruptcy Code and digitalisation are increasing investor confidence. Ample liquidity, combined with low returns elsewhere, also make the India story more attractive,” said Narayanan, adding that the domestic investor base was also increasing in the market.

Risks, though, on the rise

One downside of this bullishness in the debt market and a stable exchange rate is the potential complacency in hedging discipline.

“We have seen exporters extending their hedges, importers not hedging their exposures, corporates borrowing money in foreign currency and not hedging their exposures, and unhedged FPI inflows,” said Ananth Narayan of StanChart.

Given the rupee’s relative outperformance and depreciating levels of other currencies, including that of China’s, which has depreciated 7 per cent against the rupee since 2016, domestic industry could be in for a tough time. The rupee, therefore, should gradually depreciate in the near term, said Ananth Narayan.

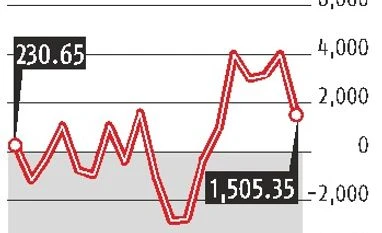

The narrowing of spread is a potent risk, too. The spread between US yields and Indian yields have narrowed in the recent period.

For example, the US 10-year treasury yield was 2.33 per cent on Friday. The 10-year Indian government bond yield closed at 6.46 per cent. The spread, therefore, works out to be 4.13 per cent, the lowest since 2010. Since 2011, the spread between US treasury and Indian yields had been on the rise, rising to as high as 6.37 per cent in March 2013.

On the equity side, things are not that rosy. The valuations are steep for foreign investors who benchmark their potential yield in India with benchmark interest rates in America. The earnings yield for the broader market is now at a record low of 3.3 per cent and its spread over the US treasury yield at a record low of 0.93 per cent. Earnings yield is the potential yield for an equity investor if the company pays 100 per cent of its current net profit as equity dividend. Typically, this should be sufficiently higher than the yield on risk-free assets (such as government bonds), to compensate for the greater risk of owning equities.

The spread was 1.9 per cent at the end of FY16 and 4.8 per cent at the beginning of the current rally in March 2013. It was 1.5 per cent in March 2008.

For domestic investors, the yield spread on equities is now a negative 3.2 per cent, down from a negative spread of 2.8 per cent at the end of March 2014, though better than the negative 4 per cent at the end of FY15.

This raises the prospect of outflow of capital from the equity market, either if the bond yield in the US hardens further or earnings yield declines further or the rupee weakens against the dollar.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)