When economies undergo structural transformation, there is an inevitable shift of labour from farming to the manufacturing and services sectors. In the words of former secretary-general of the United Nations Ban-ki-Moon, “migration is an expression of the human aspiration for dignity, safety and a better future. It is part of the social fabric, part of our very make-up as a human family”.

In India, rural to urban migration has primarily been due to push factors such as poverty, unemployment, low agricultural productivity, frequent crop failures, poor education and health care, and the lack of credit facilities. Such migration, however, does not necessarily signify a rejection of rural livelihoods, as about 70 per cent of our population is still living in rural areas.

According to 2011 Census, India has 54.3 million inter-state migrants, mostly from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal who primarily work in the informal sector. According to the report of the Working Group on Migration, 2017, only 54 districts accounted for half the male inter-state migration, and as many as 44 of these districts were in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

With economic activity coming to a grinding halt during the lockdown, the worst affected were the migrant workers — daily wage earners, unskilled and semiskilled workers, who faced immediate challenges related to access to food and shelter.

Thrown out of their jobs and with limited social and economic security, it was only natural for the panic-stricken migrant workers to decide to return to their places of origin. In the absence of rail or road transport, the crisis compelled the hitherto invisible migrants to set off on foot for their villages. Even the Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, meant to regulate the employment conditions of migrant labour did not come to their rescue. It is estimated that more than 10 million migrants have already returned to their villages, and many more are likely to follow suit.

With the lockdown restrictions now being slowly lifted, many migrants may return to urban centres, but there would also be those who would choose not to return due to their traumatic experiences and uncertainty over the pandemic.

The reverse migration means not only have the remittances to their families dried up but also a large section of the working age population has become non-productive. While increased allocation for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, free ration to migrants and other measures being taken by the Centre and the state governments are necessary for mitigating the plight of migrant labour, in the long run they have to be gainfully employed to secure their livelihood.

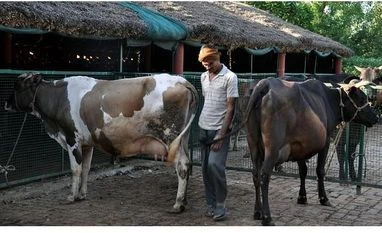

Dairying may well be a viable livelihood option for migrants, given its low capital investment, short operating cycle and steady income flow, apart from meeting the nutritional requirement of the family. During the pandemic, after an initial disruption in the supply chain, the dairy sector has managed to maintain milk supplies.

The demand for dairy-based protein compared to other forms of animal protein is likely to increase in the pandemic as it is considered a safer option than meat for nutrition. Despite successful implementation of the White Revolution in the country, its footprint in terms of coverage by the dairy cooperatives is yet to be felt in more than 60 per cent of the dairy-potential villages, most of which would also be the place of origin of the migrants.

The energy of the aspirational young migrants, many of whom bring with them knowledge and skills, can be channelised to bring about another White Revolution based on scientific animal husbandry and dairying practices. This will require well-thought-out, targeted and technology-driven programmes. These people can be encouraged to take up dairying, using technologies and adopting scientific animal rearing practices to make dairying more efficient, profitable and sustainable. With growing demand for milk and milk products, they can be incentivised to engage in processing and marketing of dairy products using innovative means. Adoption of an integrated approach to farming centred around dairying to include poultry, horticulture, fisheries, manure management, beekeeping and organic farming practices would enhance their returns and create rural wealth.

Through entrepreneurship development programmes, migrant youth may be groomed as village-level entrepreneurs who can take up input service delivery activities such as artificial insemination, animal nutrition and health services for which there would be great demand.

The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) has already demonstrated sustainable business models in these areas, which can be replicated leveraging dairy cooperatives network. The Atmanirbhar Bharat package announced by the Centre would also go a long way in rejuvenating the dairy sector. The NDDB can be entrusted and supported to create producer-owned institutions (PoIs) in villages inadequately covered by Operation Flood. These PoIs can serve as inclusive institutions which can empower migrants, rural youth and women, support their livelihoods and transform rural economy.

The other side of the story is in urban centres that are now facing labour shortage: The growth engine of our economy — manufacturing, construction and service sectors — is finding it difficult to restart normal operations. To cope with the reduced availability of workers, industries in cities and towns will have to adopt labour-saving technologies. A great learning from this unprecedented crisis for both policy-makers and employers is to ensure creation of more effective regulations and social economic support measures and their effective implementation.

Coordination across sectors and among stakeholders to promote viable livelihood opportunities in rural areas would be a necessary condition for India to meet its commitment to the United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development to “leave no one behind”.

The author is chairman, NDDB and Institute of Rural Management, Anand. Views are personal

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)