Three months into demonetisation, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a poll promise to the Uttar Pradesh (UP) electorate to waive farm loans of small land-owning farmers.

No one had thought that within two years, the contagion would spread so much that seven states would promise more than Rs 1.8 trillion to clean farmers’ dues to banks, equivalent to about 15 per cent of their annual revenue expenditure.

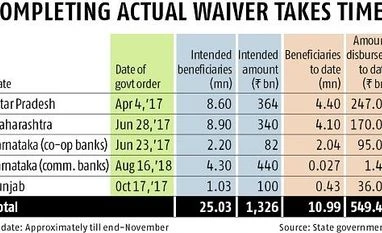

But the headline number conceals the ground reality. In four states that started the process — UP, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Karnataka — only 40 per cent of the promised amount has been waived to date, and just half the beneficiaries have benefited.

For example, UP’s scheme awarded a waiver of loans of small and marginal farmers with an upper limit of Rs 100,000 per farmer in April 2017.

It intended to benefit 8.6 million farmers by spending Rs 364 billion. After 21 months, the dues of only 4.4 million farmers — about 50 per cent of the intended — have been cleared, at a cost of Rs 247 billion, 68 per cent of the plan, to the exchequer.

In all the four states, agricultural credit disbursal to farmers has slowed in the year after the waiver. In UP, where about 44 per cent of the annual credit target used to get disbursed in April-September, the progress in 2017-18 and 2018-19 has been 34 per cent.

In Maharashtra in 18 months, 4.1 million of the intended 8.9 million (46 per cent) farmers have got their loans cleared with the state spending half the amount it promised in June 2017: Rs 170 billion against Rs 340 billion.

The case of Karnataka and Punjab is the same in terms of clearing farmers’ dues as well as with regard to credit disbursal in the post-waiver period.Karnataka is a special case since it has fully completed its first tranche — Rs 82 billion for 2 million farmers — of waiver for cooperative bank loans while its second tranche of Rs 440 billion is moving slower than usual, five months into implementation.

In Punjab, official records show of the around 1.25 million farmers expected to benefit from the loan waiver, so far, loans of around 59 per cent of them have been waived.

Against an estimated amount of Rs 100 billion that will be waived, so far the burden on the exchequer is estimated to be around 36 per cent of that, around Rs 36 billion.

Farmers in at least two, Madhya Pradesh (MP) and Rajasthan, among the three states the Congress won in the recent Assembly elections are most likely to face the same fate, since the reasons behind the slow progress are structural.

Reports say in MP too, the state government is planning to waive loans in tranches, a process, some say, could be completed only by September 2019, almost nine months from now. Experts say there are various reasons for the slow progress of a typical waiver scheme.

First, states prefer to stagger expenditure on waiver over two to three years to lessen their financial burden on the exchequer. Then, a lot of documentation is involved when a farmer needs to prove his eligibility to the bank concerned.

For example, an indebted farmer who is a government employee, or a taxpayer with income from non-agricultural sources, or owns an enterprise with an annual income more than Rs 300,000, or is an officer on the body of any cooperative society is ineligible for the benefit in Maharashtra.

In Karnataka, the conditions are less stringent, but preference is being given to loans from cooperative banks, while the dues to commercial banks are getting processed slowly. In comparison, the scheme in UP was limited only to farmers owning less than 2 hectares (5 acres), with no major conditions after that.

Officials in UP said this was the reason why the progress in UP was the fastest: Other states have not limited it to small and marginal farmers.

Further, a typical farm loan is waived when the due date is close, or it is over. This is the reason for the slow progress in Karnataka, as most of the deadlines are far away. This, officials said, helps banks and the exchequer stagger the disbursal.

Now, once a loan is waived, or settled under one-time-settlement (where the farmer pays a small amount compared to the overdue and closes the account), the credit score of the farmer account takes a hit, and, according to norms, he either becomes completely ineligible for further loans, or the loan amount that can be disbursed to him reduces, depending on credit history.

The state level bankers’ committees of all the states in question have noted this in their meeting.

“The cooperation department raised the issue that a few banks are not following scale of finance while sanctioning crop loans,” the Maharashtra SLBC meeting of August 2018 noted.

Now, the farmer becomes eligible for fresh finance only if the outstanding — principal plus interest — is cleared. If farmers whose outstanding dues are more than the upper limit per farmer set in the scheme do not pay the remainder, they become ineligible.

In such cases, banks are in a precarious position, wherein the executive branch of the government demands something that banks cannot process since it is commercially unviable.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)