The profit margin of pulses farmers fell 16 per cent on average in 2016-17 due to record production, says Crisil Research in its latest report titled Pulses & Rhythms: Analysing volatility and cyclicality and the cobweb phenomenon in prices.

The report says that if gram is excluded, margins have fallen by 30 per cent. While the selling price of pulses fell, the cost of cultivation continued to rise. The Crisil report says, "Cost of cultivation increased 3.7 per cent year-on-year in agriculture year (July to June) 2016-17, compared with 2.8 per cent in the previous year and hence increase in MSPs did little to stem the fall in their earnings."

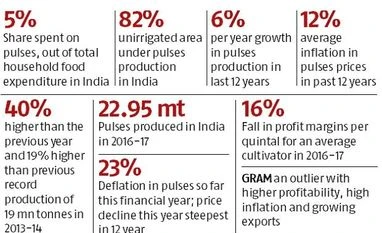

Fall in farmers' income is due to a record production of 22.95 million tonnes of pulses in 2016-17, up 40 per cent over the previous year and 19 per cent higher than the previous record of 19 million tonnes in 2013-14.

According to Dharmakirti Joshi, Chief Economist, Crisil Ltd, "Addressing the pulses issue is very crucial as they account for 5 per cent of the total household expenditure on food in India and during the past 12 years, pulses have seen an average inflation of 12 per cent."

Though pulses take up a large chunk of households' food budget and are a major component in the inflation basket, the government has not been able to manage the cyclicality well so far.

Joshi says, "The pronounced cyclical patterns in pulses hurt both producers and consumers. It is time the government initiated steps to smoothen prices through a mix of effective MSP dispensation, open trade policy and well-functioning markets. Simultaneously, the crop needs to be de-risked by increasing the irrigation buffer".

Even during the record production year, that is last year, despite the fact that government had hiked MSP of the five major pulses by an average 12 per cent on-year, wholesale prices of all pulses save gram declined eight per cent. Prices even fell below the MSP for arhar (tur) and moong during the harvest season in 2017 owing to a bumper crop and cheaper imports. Between October 2016 and February 2017, modal prices of arhar and moong were trading below MSP in major APMC mandis of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana.

During the past few months, the government fixed an import quota for tur, arhar/moong for AY 2017-18. However, the measure has come too late and has not helped farmers. Government sowing data as on September 1 shows area under pulses sowing has decreased from 14.30 million hectares to 13.76 million hectares.

This drop seems to indicate that farmers were not inclined to grow more pulses. However, there is still some optimism as the fall in sowing is not sharp.

India's pulses consumption has also grown with falling prices, as the commodity is largely price elastic. India's average import of pulses used to be 4 million tonnes and domestic production around 18 million tonnes. However, in 2016-17, with nearly 23 million tonnes and over 6 million tonnes of imports, India has built a huge surplus in the system. Despite creation of around 2 million tonnes of buffer stock in the year, the surplus is still high.

Crisil suggests a multi-pronged strategy to address the pulses crisis.

Taking example of gram, Crisil says not only has its price remained above MSP, it has also been a remunerative crop in general within pulses basket. What helped gram to buck the general trend? Gram (chana) has a high share of 40-45 per cent in production and over 60 per cent in export of pulses.

The report notes, "In gram's case, the cobweb phenomenon appears to be more prominent for international prices than domestic prices. Since there is no restriction on the export of gram, profitability remained higher for gram farmers as the international market was ready to absorb the supply in excess of the domestic demand."

Joshi recommends, "Flexibility in export policy in terms of permitting exports of restricted pulses in times of excess production can provide adequate cushion against supply shocks."

Pravin Dongre, Chairman, India Pulses & Grains Association (IPGA) says, "Pulses selling below MSP will also get support if exports are opened up. Such policies may also attract substantial FDI in this sector as India is the largest market for pulses. It will give a much-needed boost to the dal processing industry and returns to the farmers will certainly improve."

The large non-resident Indian population is paying huge premiums to procure processed pulses or dal in international market. Indian traders of premium pulses can gain substantially if exports are opened up.

To find a long-term solution, Crisil has recommended a four-pronged action plan.

1. Raise procurement under the MSP scheme for pulses

2. Flexibility in export policy, in terms of permitting exports of the restricted pulses in times of excess production

3. Since 82 per cent of the area under pulses is unirrigated, the government can invest more in expanding water-conservation techniques such as drip and ferti-irrigation to reduce the farmers' dependence on monsoon, and

4. Improve physical and market infrastructure by increasing storage and strengthening futures and forward markets.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)