India's economy gave mixed signals in 2018 with growth remaining volatile and inflation cooling.

However, food inflation reflected rural distress. On twin deficits, the fiscal deficit presented a worrying picture, and the current account deficit touched around 3 per cent of gross domestic product by the third quarter of the year.

The economy began the year with a 7.7 per cent GDP growth rate in the January-March quarter. It further rose to a two-year high of 8.2 per cent in the next quarter. When the low-base effect waned, the economy gave the real picture by expanding at just 7.1 per cent in July-September.

Economists say growth will come down in the next and the following quarters.

“Growth is likely to be 7 per cent in October-December, and will decelerate to 6.7 per cent in January-March,” SBI group Chief Economist Soumya Kanti Ghosh said.

He saw slight recovery in growth only from July-September 2019-20. However, substantial recovery will start only after that, he said.

Investments

Even as gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) grew in double digits for the third quarter in a row in July-September 2018, economists say private investments are lacklustre. The government, not the private sector, pushes up investments, they said.

GFCF rose 12.5 per cent in July-September, up from 10 per cent in April-June.

Consumption, particularly in rural areas, remained a concern. Gross final consumption expenditure, denoting demand in the economy, grew by 7 per cent in the third quarter of 2018 against 8.6 per cent in Q2 of the year.

“Investment and consumption are the worrying part. Investments are currently driven by the government and not the private sector even as the investment rate is going up. There are mixed signals for urban and rural consumption. We will have to wait for the ongoing quarter to see if there is revival,” said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings.

Akshay Modi, executive director of natural oil-processing company Modi Naturals, said industry sentiment was weak after demonetisation and the implementation of the goods and services tax, which affected the business environment.

“Private sector investments depend on the support of banks, which seem to be cash-strapped. The recent RBI norms are preventing banks from lending, which all adds up to a liquidity concern,” he said.

Inflation

However, the government managed to control inflation. The widely-tracked consumer price index (CPI)-based inflation rate declined by more than half to just 2.3 per cent by November compared to where it stood at the beginning of the year. Nowadays, the Reserve Bank of India has to statutorily keep the inflation rate in the range of 2-6 per cent.

So, now the issue would be to prevent it from falling below 2 per cent. However, economists are not worried about that. “It will rise to around 4 per cent by the end of March,” said Sabnavis.

However, here lies the problem of what was cited above as depressed rural demand. It was more explicitly shown by food inflation in the wholesale price index (WPI).

Wholesale food prices fell at a sharper rate of 3.31 per cent in November compared to 1.49 per cent in the previous month, reflecting the persistence of rural distress. November was the fifth consecutive month when wholesale prices of food items kept declining.

The picture of rural distress was also visible in the GDP data. Prices of agricultural products and those in allied activities declined by one percentage point in July-September 2018 against the rise of 1.7 percentage points in April-June, as shown by deflators.

That is perhaps the reason why the poll promise of farm loan waiver was one of the reasons why the Congress returned to power in MP, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan.

Fiscal Deficit

So far as public finance is concerned, the Centre's fiscal deficit for April-November stood at Rs 7.17 trillion, breaching the target of Rs 6.24 trillion for FY19. However, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley is confident the fiscal deficit would be reined in at 3.3 per cent of GDP as was budgeted for the year.

Economists give mixed replies. Ghosh says meeting the deficit target is a challenging task, even as the expected indirect tax shortfall could be partially offset by direct tax collections. However, Sabnavis said meeting the targets would not be difficult. If it comes to the crunch, some subsidies could be rolled over to the next year, he said.

It is almost certain the goods and services tax (GST) is not giving the targeted revenues even as Revenue Secretary A B Pandey expressed confidence that the targets would be achieved. Overall, there could be a shortfall of Rs 700 billion to Rs 1 trillion against the target of almost Rs 13 trillion. All of this may not come to the Centre only even if one assumes that states would meet the target due to the compensation cess, since 42 per cent of even central tax revenues are shared with states.

Current Account Deficit

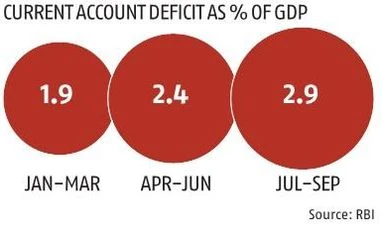

The current account deficit has risen to 2.9 per cent of GDP in July-September from 1.9 per cent in the first quarter of 2018. However, declining global petroleum prices are likely to provide relief on this front.

Ghosh, however, said the current account deficit was less of a problem now. "Our earlier forecast was 2.8 per cent for FY19, now it is 2.6 per cent," he said.

Ranen Banerjee, leader, public finance and economics, PwC India, said the fiscal deficit was easier to handle than the CAD since the government did not have much control over the latter.

Though softening global crude oil prices would give a relief on the current account deficit front, there is still uncertainty because of volatile nature of oil prices, he said.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)