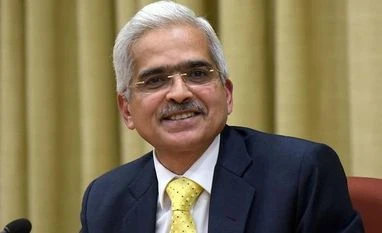

The new governor of Reserve Bank of India (RBI),

Shaktikanta Das, gained fame of a sort during demonetisation. As the person handpicked by the political leadership to face the media and explain the daily Reserve Bank of India notifications and dozens of rule changes to the general public, images of Das beamed into the living rooms of the nation every day for the month and a half.

He was chosen for this task because, by all accounts, the government was apprehensive that then RBI governor Urjit Patel would lose his legendary temper at the first sign of a tough question had he been asked to conduct daily media briefings. In that sense, it is almost ironic that he takes charge against the backdrop of increasing tensions over the central bank’s autonomy.

But this sustained exposure in the last months of 2016 also means that Das became the person that people associated with a period of despair as they struggled to get access to their hard-earned cash. And often, he was the bearer of bad news. He announced the RBI’s decision that daily withdrawal limit would be reduced to Rs 2,000 from Rs 4,500, that indelible ink will be used for those visiting bank branches so that they don’t make multiple withdrawals--a decision which was later withdrawn after widespread outrage--and defended the government line that demonetisation would only cause a short-term impact.

A day after his elevation to the head of RBI, most of the criticism on social media focused on his role during demonetisation and his academic credentials as “just” a Masters in History from St Stephens College, New Delhi, compared to two of his immediate predecessors who hold doctorates from foreign universities.

And just like the last “bureaucrat governor” Duvvuri Subbarao, the commentariat feels that Das will be beholden to the government. Those who have observed policy from close quarters, however, know that once a person goes from New Delhi to Mint Road, he assumes a mind of his own.

Das, a 1980 batch Tamil Nadu cadre IAS officer, has had two long stints in the ministry of finance, under four finance ministers: Pranab Mukherjee, Manmohan Singh (who as prime minister held additional charge), P Chidambaram and Arun Jaitley.

From September 2008 to December 2013, he served in the expenditure and economic affairs departments. As joint secretary of the budget division, he was instrumental in creating a “budget manual” in 2010, which has since served as a proverbial standard operating procedure blueprint for officers when they swing into budget preparations each year.

From June 2014 to May 2017, he was, first, the revenue secretary and then the economic affairs secretary. In the two stints, he has been directly involved in shaping eight Union Budgets. When Jaitley presented his first budget, Das was the revenue secretary and gave the minister a way out of the issue of retrospective taxation that had plagued Mukherjee and Chidambaram.

Jaitley assured markets that the government would not make any retrospective changes to tax laws that would create fresh liabilities, and that all fresh cases arising out of the retrospective amendments of 2012 in respect of indirect transfers would be scrutinised by a tax panel before any action is initiated.

A fiscal conservative, it is Das who is said to be the force behind Jaitley keeping the fiscal deficit target unchanged in his first budget and then subsequently sticking to a descending glide-slope every budget thereafter, except the 2017-8 budget.

Das also advised Jaitley to set up a new panel to discuss India’s future fiscal roadmap. He was also the Economic Affairs Secretary, under which comes the budget division, when the budget date was advanced from February 28 to February 1 and the rail budget was junked with the Union Budget.

Along with former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian, Das also attacked global ratings agencies for having different standards while assessing India and China, and in a meeting with one of the big-three agencies, also berated them personally.

A widely respected official, he has been called a “bureaucrat’s bureaucrat” by Jaitley. One of his biggest strengths is his media-management. Never evasive or arrogant in his dealings with the press corps, Das has also been crucial in behind-the-scenes, informal communications between the RBI and government over the years. Officials who have worked with him in North Block say that he is accommodative of all views and will give everyone a patient hearing in meetings before taking a decision.

It is possible that Das will also be the governor most active on social media. As of writing this piece, his Twitter account is yet to be verified. However, he has tweeted actively on all government issues even after he retired in May 2017. Indeed, many considered his tweet on the one-year anniversary of demonetisation as singularly insensitive.

So it is not surprising that Das does not have a controversy-free track record. Bharatiya Janata Party’s Member of Parliament and Jaitley’s bête noire, Subramanian Swamy, has constantly attacked Das. He has been accused of helping Chidambaram in the Aircel-Maxis case, of being involved in a land allotment scam in Tamil Nadu, of nixing the Department of Revenue Intelligence’s probe regarding coal imports, and of meddling in the affairs of the Enforcement Directorate. None of these accusations have been proven.

Just six months after retirement, Das was also made a member of the 15th Finance Commission. The Commission has already visited 13 states and is collating data to create its report. He also served as India's Sherpa to G-20.

Das comes at a time when the relationship between the government and RBI have reached a nadir. On Tuesday, he already proved he is different from his predecessor by holding a long press conference and answering questions patiently. A governor who tweets regularly and answers media questions is quite unprecedented. Perhaps a sign of things to come.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)