The acerbic comment shows the deep divisions within the Pay Commission to address the biggest challenge the Indian government is facing now - lack of adequately trained personnel at policy level.

As of now, there are only 30,000 people employed by the central government in its Bhawans in New Delhi and other cities who create and oversee government policies and schemes for 1.2 billion Indians. Tucked away within the 875-page report of the Commission is the rank-wise break-up of these men and women. Of them, those who are section officers, the lowest executive rank position in the government, and up to the Cabinet Secretary are less than 4,000. "The core of the government, so to say, is actually very small for the government of India, taken as a whole," the report notes.

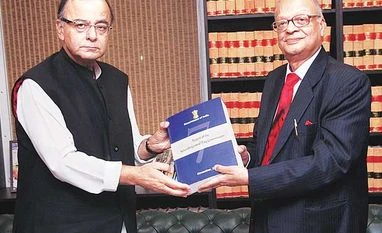

Because of the differences, despite a clear mandate, the Pay Commission report has not been able to offer any solution to the manpower shortage at the policy level. Speaking about the missed opportunity, Rathin Roy, director of National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, and a member of the Commission, told Business Standard: "There was a reforms freeze because of the dog fight among us."

One of the terms of the Pay Commission was to "work out the framework… to attract the most suitable talent to government service… and foster excellence in the public governance system to respond to the complex challenges of modern administration (including building up of)… capacity through a competency-based framework". This couldn't be done as the three members differed drastically on almost all of these issues.

Even after including all support staff, an analysis of the staff strength carried out by the Commission shows India has a much smaller civil service than the US even though the latter supposedly leaves many of the government responsibilities to the private sector. The total number of Central government personnel per 100,000 of population in India is only 139, against the US' 668. The total number of civil servants employed by the US is 2.13 million, whereas India makes do with 1.8 million.

Drilling further down into those figures, the Pay Commission report shows that excluding the railways and the postal department, the ministries of home, defence and revenue department account for 82 per cent of these government employees.

The shortage gets worse at the officer level where the actual government service is supposed to be delivered. The number of officers in the ministries is less than 4,000; by including those deployed in attached and subordinate offices, they add up to 91,501 or three per cent of total government employees. Of them, seven officers run the capital markets division in the finance ministry, about 10 manage the anti-dumping department in the ministry of commerce.

The huge under-staffing is the clear reason why the Centre is often unable to deal with all that Parliament asks it to do. Yet, a possible reform to widen the pool has got scuttled by the differences among the Seventh Pay Commission members.

Rae says: "Merely increasing the number of officers available on the panel would be an exercise in futility. While domain knowledge is relevant; it is not the most important factor at policy making level, where general management skills play a more important role."

The Commission also found that personnel (officers and non-officers) between 50 and 60 years of age account for 29 per cent of the total workforce - an indicator there is going to be an even deeper skill shortage in the coming years.

The grim prognosis of the Commission: Losing experienced high-level personnel entails unquantifiable costs as new recruits will require training and on the job skills, a costly enterprise for the government.

You’ve reached your limit of {{free_limit}} free articles this month.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

Already subscribed? Log in

Subscribe to read the full story →

Smart Quarterly

₹900

3 Months

₹300/Month

Smart Essential

₹2,700

1 Year

₹225/Month

Super Saver

₹3,900

2 Years

₹162/Month

Renews automatically, cancel anytime

Here’s what’s included in our digital subscription plans

Exclusive premium stories online

Over 30 premium stories daily, handpicked by our editors

Complimentary Access to The New York Times

News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter & The Athletic

Business Standard Epaper

Digital replica of our daily newspaper — with options to read, save, and share

Curated Newsletters

Insights on markets, finance, politics, tech, and more delivered to your inbox

Market Analysis & Investment Insights

In-depth market analysis & insights with access to The Smart Investor

Archives

Repository of articles and publications dating back to 1997

Ad-free Reading

Uninterrupted reading experience with no advertisements

Seamless Access Across All Devices

Access Business Standard across devices — mobile, tablet, or PC, via web or app

)