The daily dose of news on the Sunjwan terror attack, and the high pitched debates (there was one in which two people jumped up from their seats because sitting down and shouting apparently does not convey the true depth of your feelings), have now been replaced by the Nirav Modi loot. The media has moved on to the next sensational story but for the Indian Army, the problem of protecting its camps remains a live issue.

I was the Army Commander when camps and garrisons like the Mohura gun position, Uri and Nagrota were breached by terrorists, causing a large number of casualties. I know that it is hugely frustrating and extremely difficult to explain what is commonly seen as a lapse and laxity by the military in protecting itself. Obviously, human error can never be ruled out, but merely blaming the sentry or the local commander is a very simplistic explanation of the problem.

We have to look for a comprehensive strategy which looks at incidents of violence in Jammu and Kashmir in its entirety, including the attacks on police and army camps. Sometimes we are unable to focus on such a strategy because individual incidents like Sunjwan tend to dominate the media and security discourse and we end up trying to find immediate solutions rather than pursuing a long term and consistent approach. For both the electronic and social media, today's events are the only news, yesterday has already been forgotten and tomorrow will bring another scandal. The government scrambles to repair the immediate damage and has little time to think of policies and strategies. This has to change.

Physical garrison security is obviously important but perhaps the easiest to fix if we look at the Kashmir conflict in all its shades. A blend of best practices in military procedures and technology to secure the perimeters is the answer. Soldiers are highly motivated but no robots. They tire and eyes can only see a few feet at night. They need to be empowered with technology which is readily available off-the-shelf. The fact that this has not yet been extensively done despite numerous attacks is a classic example of how bureaucratic procedures sometimes take precedence over human cost. However, the funds recently released could help overcome many of the current problems in garrison security.

The more difficult challenges come in tackling the Pakistan army, and bringing calm to the internal situation in Kashmir. We may feel that these two issues have little to do with attacks on security forces' camps but the fact is that such attacks are a part of the overall deterioration in the security situation, both along the line of control and in the Kashmir valley. Hence the larger issue of the external and internal dimension of the Kashmir conflict will have to be addressed.

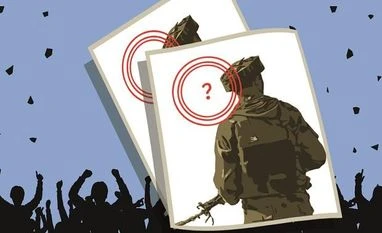

All the past attacks on security forces' garrisons have been carried out by heavily armed groups that have infiltrated from Pakistan one or two nights prior to the attack, for hitting a specific target. If terror groups can move with such impunity close to what is perhaps the most heavily guarded border in the world, Pakistan army connivance is obvious.

But how do we deter an army that has made the bleeding of India into a crusade? Diplomacy is defunct, the much talked about 'international isolation' has not manifested in any change in behaviour, and there are no economic linkages which can be exploited. Therefore, are we left only with the military option to pressurise Pakistan?

The regular military officer is not like the ones we see on television baying for blood. More than a century ago, De Tocqueville said, “In a political democracy the most peaceful of people are generals.” Having seen at close hand the loss of comrades and horrors of conflict, Sun Tzu's advice “to subdue the enemy without fighting” is taken seriously. However, we also cannot flinch from the use of force when it becomes unavoidable. We seem to have reached that point. Therefore, let us resort to the use of this instrument with a well thought out plan and in a calibrated manner.

The main centre of gravity in any internal conflict is the population, and Jammu and Kashmir is no exception. We have generally followed a narrow security-centric approach which measures success by the number of terrorists killed, infiltrators foiled, violent incidents etc. The growing alienation and radicalisation among the people of Kashmir has often been talked about but not tackled. Therefore it should come as no surprise that the Sunjwan attackers enjoyed some local support.

It is essential that an environment be created in which the locals show greater faith and confidence in the government rather than the terrorists. As General Gerald Templer, who led the successful counterinsurgency campaign in Malaya, stated, “The shooting side of the business is only 25% of the trouble and the other 75% lies in getting the people of the country behind us.”

If the internal situation in the state calms down, the motivation and support for Pakistani acts of terror will automatically reduce. Obviously, this will require a coherent and consistent strategy where we may have to revisit some of our traditional practices and question traditional wisdom.

The attacks on camps are in many ways a manifestation of the overall security situation in Jammu and Kashmir. Therefore, in finding a solution for this problem, it would be prudent to look at the larger picture, both externally and internally.

D S Hooda retired from the Indian army as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Northern Command

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)