Consumption is dwindling in Bihar. You can’t tell that from the plethora of new restaurants in Patna or the number of new motor car showrooms in Purnia, the eastern-most town of the state. But head to the rural and semi-urban areas of Bihar, which is one of India’s poorest states by per capita income, and the reluctance to spend on consumer goods is palpable.

Binda Devi of Simrahi Bazaar in Supaul district is sure that she does not wish to buy a television for her kids. “Woh to aise hi mobile dekhte rahtein hai, TV nahi layenge (they keep watching mobile phones anyway — so we won’t buy a TV),” she says. She would rather buy a cow instead, and is waiting with her husband, Dilip, who does “computer embroidery” in Delhi’s Gandhingar market, for a loan from a micro-finance company. They used to have a cow a long time ago and now want to buy another one so they can sell the milk to the local collection agency.

Electricity has arrived in all the villages in the state. But still, there is no rush to buy televisions or other consumer goods. On the main market road of Simrahi Bazaar, there are plenty of shops to repair agricultural tools, but hardly any for consumer durables. The same story plays out as you go deeper into the hinterland. In Shihuli village in Dhamdaha block in Purnia, Rekha Devi leads a group of women who have come to a micro-finance company to apply for loans. What is the largest item of expenditure in her family? Education for her two children, replies Rekha Devi. Sitting on a mat with the loan assessor, her companions, Hawa Devi, Sughani Devi and Ranju Devi, agree with her.

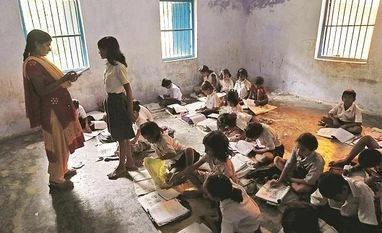

Most of their children are enrolled in the government-run school which lies three kilometres outside the village. But they are disgusted with the quality of teaching there. “Masterji class men awiche, mobile ghumaike chale jaiche (the teachers come to school, play with their mobiles, and then leave),” says Rekha Devi. She says since they belong to a lower caste, they don’t have the courage to tick off the teachers. So they want to send their children to the private schools, where the fees eat into monthly budgets.

It is in this context that the strike by about 450,000 contract teachers from the middle of February is making headlines in the state. The contract teachers are demanding pay parity with permanent teachers. This being the examination season, the state government has been scrambling to arrange for substitutes for the striking teachers.

The slump in consumption is visible in other parts of Bihar too. Darbhanga town, 140 km from Patna, now has a mall with a Big Bazaar outlet and other shiny stores. A kilometre of jewellery shops runs through the centre of the town. Crowds throng both the mall and the jewellery strip, but one doesn’t see much business happening in either of them.

Forbesganj town in Madhubani district has a gleaming three-storied Royal Enfield showroom. In Bhawanipur, close to Madhepura, there is a Honda motorcycle showroom. The enticements are there, but few are showing up to yield to them. The per capita income of Bihar, which goes to the polls in November this year, has been inching up lately. It was Rs 42,242 in 2017-18, about 12.7 per cent higher than the figure for 2016-17, but even that is just 37 per cent of India’s national average. However, the small rise in the per capita income notwithstanding, it is obvious that people’s expenses in education and health leave them with little scope for other kinds of spends.

Something else is happening in Bihar, which has made education people’s top priority and forced them to cut back on consumption. Men who went to work in the big cities are gradually trickling back into their villages and small towns. Having seen the life in the city, they are keen to educate their children and give them a better start to their lives.

Santosh used to sell chow mein from a cart in Delhi’s Kashmere Gate. He has chucked it up to return home. He stands chatting with this correspondent while he waits at a micro-finance company’s branch in Singheswar in Madhepura district. Shivratri is just days away, and there will be a huge fair in the town. The lagan (marriage) season will start soon after. Santosh’s wife, Asha Devi, has applied for a loan to set up a stall for knick-knacks so they can capitalise on the busy season. They already have a shop, but plan to migrate the business to the mela for the next few days. Once they get the loan, they will go to wholesalers to buy their stock. Would a shop here do better than a chow mein stall at Kashmere gate? Santosh admits that it would not, but on the bright side, he would be spared the cost of the train journey and the cost of leading even a bare-bones existence in the city.

Mohammed Abul Salam is the owner of Azaad Band in Singheswar town. He wants to take a loan so he can take his band all over the district and play at weddings. He shows his interest in a proposal for an education loan, too, and says there would be plenty of takers for it.

Salam is happy that people are quitting their city jobs and coming back home. His band’s flute player, too, has returned from Haryana. “Logon ko yahan aajkal kaam mil raha hai, to bahaar kyon jayenge (since people are getting jobs here, why should they go out of the state)?” he asks.

Concluding part on March 8

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)