The new skill development minister, Dharmendra Pradhan, has a strong track record in digital schemes to deliver subsidised gas to needy households. But he is in for a challenge in the vocational training sector, less amenable to scale economies, woefully dependent on private industry and saddled with the burden of expectations set, first by the outlandish targets declared by the UPA in 2010 (of 40 crore workers by 2022) and then by the marketing hype of the NDA’s Skill India.

In 2015, over 30% of India’s youth was neither employed nor in education nor training, one of the highest percentages in the world. The just-released Niti Aayog report declares that jobs are not being created fast enough, but also that the jobs available are of poor quality. The solution: the oft-heard mantra of more, and quicker, labour reforms. But Niti Aayog’s outgoing chairman has himself admitted that this conventional explanation is lacking, and that the real cause relates more to the aversion of a growing cohort of Indian industry to get bogged down in labour-intensive processes.

In 2014, I was charged with finding jobs for Skill India-trained entrants from Eastern India in Delhi-NCR’s auto-components and electronics industries. The assignment allowed me a vantage point on the skills gap – that between the supply of provincial youth armed with skills certificates, and the demand for workforce from production plants serving Indian and global markets. What do such jobs look like for new entrants? And is the government skills policy helping to deliver jobs, and better jobs?

Today’s workforce managers in global industrial plants face a number of challenges. They need workers – sometimes in large numbers (as many as 100-200 at a time) – but they can only sustain these jobs when work is available. What’s more, most jobs are not only poorly paid but uninteresting – requiring, for example, a micro-routine of gestures to be endlessly repeated on an assembly line, the monitoring of one or two machines or a fixed routine of quality checks. Such jobs offer scant opportunity to learn and progress.

How do companies succeed in cranking into place a workforce which fits these unpromising conditions, where workers are increasingly aware and have growing aspirations? By following a few basic rules, none of which augur well for Pradhan or Modi.

Rule Number 1: Avoid regularising workers, while never completely dousing their hope

In spite of the clear limits framed in labour law, it is now relatively easy for firms to hire short-term en masse. Some do this by using labour agencies – contractors – for functions across the shop floor. 4P Logistics is one such contractor, feeding several thousand workers into Japanese and other global automotive and electronics companies in Bawal’s industrial area off the highway to Jaipur, where joining formalities include signing a letter of resignation and four blank forms (a criminal offence in India). Upshot Nissan, another such agency, provides more than 20,000 workers to 140 companies in the automotive components sector of Sriperumbadur, outside Chennai. One of its largest clients is the Renault-Nissan plant to which Upshot supplies more than 2,800 workers.

Contractors like Upshot and 4P do not procure workers; they simply assist in their just-in-time allocation. With no ties linking contractor and worker, such third parties are poorly placed to address attrition, which climbs to above 30% monthly. But crucially, they act as aggregators – helping in the efficient allocation of manpower and keeping wages down. The fees paid to contractors, one manager explained to me, buys peace of mind that the assembly line will be filled each day, regardless of with whom.

Across the NCR in Greater Noida, contract labour is not so easy to come by since it has been restricted by the state government in Lucknow. But companies find alternative ways to avoid regular hires. The Korean giant LG, with its sparkling campus of 3000 workers making fridges, washing machines and air conditioners, has not added to its small cadre of permanent workers since 2009. Instead, temporaries are hired on a daily basis for up to six months. Workers punch in and out at the factory gate to clock up their wages. On the seventh of the following month, their thumb print delivers the cash they’ve earned, just like an ATM! No payslip, no letter of appointment, no relation with HR staff nor contractor, just a machine.

Another way to avoid regular hiring is through apprentices, who can be hired for just a year on well below the minimum wage. At the expansive corporatesque plant of Samsung in Noida, 2G and 3G phones and flat screen television sets are assembled by apprentices aged strictly between 18 to 22 years. While the wage package might appear to get close to the legal minimum, there is no statutory social security benefit (ESI, PF) and nearly a third of the wage is conditional on attendance. Following only five days’ induction – in which trainees learn the ‘3Ms’ (my job, my area, my machine), machine safety and fire safety – apprentices are fully integrated into the tightly surveyed assembly line alongside other operators where they remain until year end.

Contract workers, temporaries and apprentices – three tried and tested ways of flexible hire and fire. The flexible worker system has three major functions. It provides firms a way to observe worker behaviour over time, ensuring only the most compliant make the grade into the shrinking pool of regular jobs. Second, it is a mechanism of control, where workers find that raising complaints of any kind can lose them their job. Third (the one employers like to cite), it is a hedge against capricious global markets.

Of course, the system has to be presented to new recruits in such a way as to keep the faint hope alive of a permanent job. One HR manager, quite without irony, outlined the many steps towards secure employment: First, he advised, you must work under the contractor, the procedure for which is an interview focused on behavior and ‘etiquette’; then, take a written test and have a chance to pass into ‘company casual’. Then, another written test and after three years, you can become a trainee. After another three years and a written test, you can become a company permanent. A regular job in this firm, it seems, is to be enjoyed in one’s next life perhaps.

Rule Number 2: Keep the regular workers sweet and they’ll help you manage the rest

Workers flexibly hired and fired are flexible with their loyalties. The whole endeavour – of maintaining the cooperation of such a huge casual workforce – is a delicate balancing act and hence, many companies enlist the help of their privileged minority of permanent workers. Honda Motorcycles’ first plant in Manesar witnessed violent clashes between workers, police and management throughout the 2000s, culminating in 2012 with a generous settlement to permanent workers at the cost of all casuals who had earlier joined the protest. Today, while their number slowly dwindles, permanents nonetheless assist management to keep casuals in check, their loyalty refreshed with periodic agreements. In the more recently established Honda Cars plant in Greater Noida, the union has acquiesced to the ceiling on bargainable jobs (today at 15% of the total), and now seeks to corner as many of the short-term appointments as possible for the ‘sons of the soil’ communities from which its membership is drawn. The company can secure the ratio of casuals it desires only by conceding recruitment powers to these caste-based lobbies.

Rule Number 3: Close mature plants and move further out

The recent geopolitics of industrial plants shows that avoiding regular hires and winning over the union may not be enough to ensure the smooth supply of trouble-free workers. Companies such as Honda in NCR and Yazaki in Pune have migrated from industrial areas to greenfield sites in spite of abundant labour supply, expressly to avoid trouble.

When Honda Motorcycles’ Tapukera plant came on line in 2010, it set out to ensure the company should not suffer the breakdown in industrial relations which had befallen its Manesar plant. Shifting south meant sourcing its workforce from villages, from outside the pool of wary and seasoned labour circulating around the Gurgaon-Manesar belt, and from migrant batches who could be counted on to keep to themselves. Pune-based Yazaki, the Japanese global leader in wire harnessing, transformed its workforce from one dominated by ‘bargainable’ posts in its old Wagholi plant, to one made up exclusively of casuals (nearly 2000 of them) all on six-month contracts, in its new Ranjangaon plant further from the city. The key is to shed ‘old’ labour and start afresh, with workers – both local and migrant – still linked to the farm and the informal sector.

Rule Number 4: Play to status

While these jobs offer low wages, no security and scant chance to learn and progress, they involve expensive equipment that must be safeguarded. The costs – of installing and maintaining the stream of workers, of making them work at pace, of hiring and inducting the churning recruits – are inescapable. As the equipment becomes more expensive, and the workforce more flexible and footloose, these costs only rise. The faster the production targets, the more expensive the machines, the more must be invested in a system of surveillance and extraction to keep it all going.

It is here that industry makes use of the status aspirations of educated youth. Armed with 10 years of schooling and ITI certificates, the youth – freshly accredited by one of Skill India’s short courses – resist the humiliations endured by their fathers and hold out for jobs which meet their status benchmarks. The cleaner the industry, the less time out in the sun, the smarter the brand, the higher the technology… the better the job. Industry has learned that if they are able to keep alive – and even meet in a few gestures – these aspirations, then they can go some way to safeguard compliance and cooperation of this youth on the shop floor.

There are two ways by which industry achieves this. First, through entering partnerships with educational institutions. Such institutions are approached not as vocational training providers but as workforce temping agencies. While old-style labour contractors struggle to attract and retain aspiring youth, institutions have stepped in, offering a package of ‘learning and earning’. Wages are pitched somewhat below the legal minimum, while tuition fees are low and easily managed by deduction from wages at source. Worker-students attend classes outside working hours and trudge through the syllabus of private or government universities offering distance certifications for diplomas and degrees, often for periods of three years or more. Such arrangements enable employers to retain entry-level workers for longer periods while legitimately managing them as a separate group from their shop floor peers, thus keeping at bay the risk of industrial unrest.

Second, global manufacturing plants accommodate the aspirations of educated youth in their outward markers of status, in the plant, in job titles and procedures. Samsung’s assembly jobs are badly paid but remain popular among entry-level youth for the brightly-coloured corporate style canteen, the campus sports facilities and the gift of a Galaxy phone at first Diwali bonus. On the other hand, ‘housekeeping’ jobs in GSH, a leading facilities management firm, pay Rs. 5,000 more per month but are rejected because they involve some cleaning work. The automotive giant, Anand, takes only those with diplomas – a 3-year course one can take if one has a10th school certificate – and calls them ‘trainee staff’, explaining that this helps to avoid the ‘labour mentality’. In breaking down the distinction between ‘staff’ and ‘workers’, the firm nimbly eliminates the legal and bargainable category of ‘workmen’ from their shop floors.

Employers recognize that it is status and white-collar aspirations that make young schooled workers less ‘troublesome’. The less people consider themselves ‘workers’, goes the argument, the less the risk of industrial relations problems. Employers play on such aspirations to achieve the tie-in and control they need, without giving away their flexibility. There is even a sense by which the status markers offered by employers and institutes act as compensation for shabby jobs.

Conclusion

The jobs offered in the large automotive and electronics plant of the capital region and elsewhere are overwhelmingly casual, short-term, insecure and poorly paid. We may hope that the flexibility claimed today by industry de facto may be somewhat curtailed when de jure reforms come to pass, but enforcement remains a huge question mark. The global and mechanized character of these industries reinforces the uncertainty and slow growth established by recent economic trends. There is scant sign that government skills policy has improved job quality, and, by subsidising the stream of new entrants at no cost to employers, it may have had the opposite effect and even kept wages down. At best, the skills policy in these sectors has helped to preserve existing jobs and – perhaps – to create more jobs at this low wage-high flexibility price point.

The oft-cited failure of industry to engage in the government’s skills policy is partly explained by the fact that in many industries, skill is simply not the binding constraint. There are industries where the skilled workforce is long established (the textile and garment industry, for example); there are industries where technology changes so rapidly that companies plan for in-house training (the electronics and capital goods industry, for example). And there are industries where automation levels have reached a point where the majority of roles are unskilled. As one auto components manager explained, there is little need for skilled and long-serving workers where production is modularized and problems can be easily diagnosed.

But that skill may not be a key constraint of industry has not prevented industry from taking advantage of the government’s skills policy, if in undeclared ways. My experience has shown that Skill India serves industry in two important ways: in helping to maintain a steady stream of flexible workers, and in providing a way to tie in these better educated workers for longer periods on trainee contracts through partnership with industry. It is to secure the availability of compliant and flexible workers at minimum cost, rather than to access a better skilled workforce, that industry has engaged with Skill India.

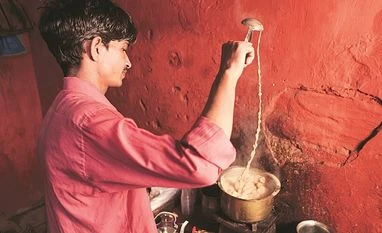

In this endeavor, the status aspirations of India’s schooled youth play a key role. Such status is embodied in a higher qualification (a diploma or a BBA, for example), in the preference of certain jobs over others. It is also embodied in the trappings of white collar life, such as urban living, a smart phone and a cosmopolitan ‘personality’. The aspiration is consistent: to ratchet up enough status pegs to avoid a slip into manual and casual labour, of the type which is viewed as undervalued, disrespected and dirty. The aspiration to be ‘out of the muck’ is fueling the rise in NEETS – young persons who are Not in Education, Employment or Training – discussed above. Notwithstanding the efforts of the National Skill Development Corporation and its Sector Skills Councils to remove the ‘stigma’ of vocational training and manual skill, students, industry and training providers converge in their acceptance of a system which excels more in ‘pen and paper’ certificates than in building deeper competencies. The creation of a register of value by which manual skill can be seriously assessed and respected has repeatedly eluded policy makers, when critical steps are trivialized by rushed timeframes and outsourcing. For example, the building of India’s national occupational standards in 2014 was a rushed job, outsourced to global consultants Ernst and Young and Price Waterhouse Coopers with little engagement from industry.

Workers who once aspired to ITIs and permanent jobs now aspire to diplomas and degrees, to become junior staff in a world where permanent workers are obsolete, to own smart gadgets and to enjoy corporate privileges. No matter what industry wants, commented one senior plant manager at Graziano, Noida, “in India, everyone’s in a race to get a white collar”.

Orlanda Ruthven works on employment and labour standards in India. She is co-author of the widely acclaimed Portfolios of the Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on Two Dollars a Day’.

By arrangement with thewire.in Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)