The unemployment rate rose to a four-year high in 2016-17, when the government demonetised old currency notes, at the same time as more people joined the labour force looking for jobs, according to the findings of the Labour Bureau.

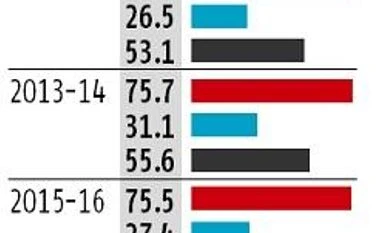

The unemployment rate stood at 3.9 per cent, compared to 3.7 per cent in 2015-16 and 3.4 per cent in 2013-14, says the Bureau’s Sixth Annual Employment-Unemployment Survey. The unemployment rate refers to the proportion of the labour force available for work but unable to get a job.

The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) is the proportion of the working age population working or seeking jobs and this went up to 76.8 per cent in 2016-17 from 75.5 per cent in 2015-16, said the report. However, women continued to exit the workforce, particularly in the rural belts of the country.

Extracts of the report, which has been withheld by the Labour and Employment Ministry, have been reviewed by Business Standard. It is the last annual survey of households on jobs conducted by the Labour Bureau as this is being replaced by the National Sample Survey Office’s period labour force survey. The NSSO survey, which will cover 2017-18, is yet to be released. Sources said the Labour Bureau’s report was approved by Labour and Employment Minister Santosh Kumar Gangwar in December but its public release has been withheld by the ministry.

“The Labour Ministry may release the findings when the results of surveys on employment provided by the Mudra scheme and another one on employment conducted by the NSSO are made public,” the source said. In fact, Gangwar did not disclose the report’s findings during the recently-concluded winter session of Parliament. When MPs asked questions about the job numbers, Gangwar provided figures from the Bureau’s previous surveys.

Nor did Gangwar respond to a questionnaire sent by Business Standard on Wednesday. Labour and Employment secretary Heeralal Samariya did not reply to a question on why the ministry has delayed the release, despite the fact that Gangwar has approved the report.

“There was a sharp dip in the unemployment rate in 2013-14, the year before the new government took over. After that, the unemployment rate is crawling up and it is going back to the level of 2012-13, the worst year in terms of jobs,” said former chief statistician of India Pronab Sen.

Experts said that women dropping out of the workforce on the one hand and a rising joblessness trend on the other, points to a lack of decent and productive jobs for them. However, the Labour Bureau’s report has failed to capture the full impact of the November 2016 demonetisation because the field work took place earlier, between April and December that year.

Joblessness among females touched 6.1 per cent in 2016-17 – the highest since the Labour Bureau started conducting its annual surveys in 2010. This was almost double the joblessness seen among males (3.3 per cent) in 2016-17. In 2015-16, the unemployment rate among females stood at 5.8 per cent.

“Female participation in the workforce is declining as women are being encouraged to go for higher education, instead of seeking jobs. On the other hand, the unemployment rate among females is particularly high because of various social reasons. There are still families where it is customary and desired that women do not work,” said S P Mukherjee, chairman, Standing Committee on Labour Force Statistics.

Unemployment was particularly high in urban areas compared to the rural parts of the country in 2016-17. For instance, the unemployment rate among rural women continued to be the same as the previous year (4.7 per cent) and for rural men it rose from 2.9 per cent in 2015-16 to a four-year high of 3.1 per cent in 2016-17.

But in urban India, joblessness among males rose sharply to 3.8 per cent from 3 per cent in the previous year and among females it went up to 11.2 per cent from 10.8 per cent.

The LFPR for males rose to 76.8 per cent in 2016-17 from 75.5 per cent in the previous year. However, the LFPR for females declined to 26.9 per cent from 27.4 per cent during this period. This means while more men are becoming part of the workforce, women are leaving it for reasons that range from pursuing education to conforming to social traditions that expect women to stay at home.

“The LFPR is constantly falling for women. It has declined sharply in the rural areas where economic conditions have worsened since 2014. It is a case of the overall supply of work drying up and men taking over more jobs in the villages,” said Sen.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)