Like many global investors I am leery of big government. But I did not come to this view on Wall Street. It came to me growing up in India, watching lives ruined by the broken state, including the public hospital that hastened the death of my grandfather by assigning an untrained night aide to attempt his emergency heart surgery.

As an idealistic 20-something in the late 1990s, my hope was that India would one day elect a free market reformer like Ronald Reagan, who would begin to shrink the dysfunctional bureaucracy and free the economy to grow faster. Looking back, I see how clueless I was.

In Delhi every politician is wedded to big government, and there is no constituency for free-market reform. I kept hoping for Reagan, and India kept electing Bernie Sanders.

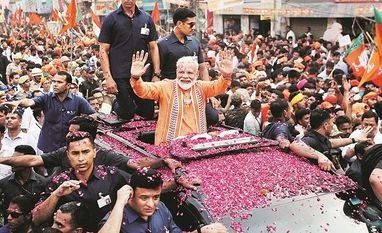

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is no exception. Five years ago he led the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, known as B.J.P., to power on a Reaganesque promise of “minimum government,” and now he seeks a second term in the general election that ends on Thursday.

But in office, Modi has wielded the tools of state control at least as aggressively as his predecessors. In this campaign, he went toe to toe with rivals, vying to see who could offer the most generous welfare programs, and it appears to have worked. Exit polls released Sunday showed the B.J.P. and its allies with a commanding lead.

This should surprise no one. India’s political DNA is fundamentally socialist. After independence in 1947, India established a parliamentary democracy, and a deeply meddlesome government to spread the wealth to its impoverished masses.

But if Indians were ready for political freedom at such an early stage of development, I often wondered, why not economic freedom?

My hopes focused first on the Gandhis, the leading dynasty of the Congress party, now the main national rival to Mr. Modi and the B.J.P. Perhaps Congress would find its worldly reformer in Sonia Gandhi, the Italian-born widow of Rajiv Gandhi, the prime minister slain in 1991. Later I saw hope in Sonia’s son Rahul, a Cambridge graduate who had worked at a London consulting company and now leads Congress’s 2019 campaign.

In late 2002 I arranged an hourlong meeting with Sonia and Rahul in her office at 10 Janpath, a four-acre oasis in the heart of Delhi, where the décor was utilitarian but the protocol was regal. In the waiting room Congress party bigwigs lined up before Sonia’s mustachioed private secretary, Vincent George, begging for permission to enter her inner sanctum.

Ignoring the quasi-feudal scene, I made my case for modernizing India, emphasizing the political gains Congress could make by extending freedom to the economy. Congress had been losing support for years, while emerging world leaders like Kim Dae-jung of South Korea and Vladimir Putin of Russia had been gaining popularity by focusing on reforms that would boost economic growth.

The Gandhis asked skeptical questions: Were the countries I cited real democracies? Would free market reform help the poor and create enough jobs for India’s unemployed masses? Still, my contact in the Gandhi camp gave me reason to think they would follow up. But they never did. Free market reform is antithetical to the socialist ideology of Congress, which is now promising a $1,050 basic annual income for India’s poorest 50 million families.

Hopes for a big-bang Indian reformer revived years later with the rise of Mr. Modi, who in 2002 had been elected as chief minister in the western state of Gujarat. By courting multinational companies, building roads and streamlining the state bureaucracy, Mr. Modi oversaw an stunning boom. The state economy grew at a pace close to 12 percent annually in his first term. In 2014, Modi’s record in Gujarat helped lift him into the prime minister’s office.

Like many India watchers, I heard in Mr. Modi’s call for “minimum government, maximum governance” the voice of a red-tape and regulation-busting reformer in the Reagan mold.

In retrospect this reading ignored how Mr. Modi had delivered “maximum governance” in Gujarat: by force of personality, cutting foreign investment deals himself, intimidating bureaucrats into building roads on time without demanding bribes.

This was economic development by executive order, not economic reform by systematically expanding freedom. Mr. Modi has tried to govern India the same way, but the top-down commands that rallied tens of millions of his fellow Gujaratis worked much less well on the sprawling Indian population of 1.4 billion.

He centralized power in the prime minister’s office, and many private business people now say he treats them much as his socialist predecessors did, often suspicious of their motives and contribution to society.

One November evening in 2016, he ordered the withdrawal of large rupee bills — 86 percent of the currency in circulation — at midnight. The aim was to flush cash out from under the mattresses of rich tax dodgers. One of his cabinet ministers said Mr. Modi was delivering on a “Marxist agenda” to reduce inequality.

Today, however, the aftershocks are still rippling through the economy, and have been especially painful for the poor.

In some ways Mr. Modi has proved more statist than the Gandhis. Before he took power he criticized Congress welfare programs as insulting to the poor, who “do not want things for free” and really want “to work and earn a living.”

As prime minister, Mr. Modi doubled down on the same programs, expanding the landmark 2006 act that guaranteed 100 days of pay to all rural workers, whether they worked or not.

On the economic front, then, every Indian party is on the left, by Western standards. The Congress traces its economic ideology to socialist thinkers, but the B.J.P.’s thinking is grounded in Swadeshi, a left-wing economic nationalism. Regional parties, an increasingly important third force, are inspired by the same Indian socialist heroes, like Ram Manohar Lohia.

It is true that several Indian prime ministers going back to the 1980s pushed free market reform. But they did so only when forced to by a financial crisis, not out of conviction, and certainly not now, after five years of reasonably strong growth. This year the B.J.P. has been announcing new government programs that would make Mr. Modi feel right at home in a Bernie Sanders town hall meeting, including cash transfers for farmers, wage supports, free health care and a pucca (concrete) home with gas and electricity for every Indian family.

This is not the Modi portrayed by the foreign press, which casts him as an extreme right-wing nationalist. His campaign may well have stirred up India’s Hindu majority against the Muslim minority. But on the economic front, Mr. Modi is as far left as any Indian leader in memory. And if he does win a second term, he is much less likely to govern like a Reagan than a Sanders.

Ruchir Sharma, a contributing opinion writer, is chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

The New York Times service

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)