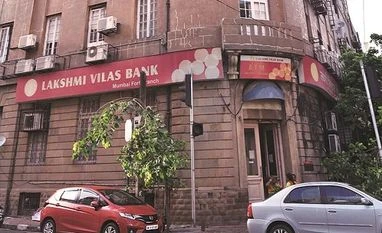

For the past two weeks, old private banks — those that existed during bank nationalisation — have hit the headlines for wrong reasons. Whether Lakshmi Vilas Bank (LVB) or Dhanlaxmi Bank, issues around corporate governance, mismanagement, differences between promoter groups and even the effectiveness of shareholder activism were being raised — which ultimately question whether the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has monitored these banks adequately.

Several of these banks were placed under the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework of additional regulator scrutiny but this does not seem to have stemmed the rot (see table). “Placing banks under PCA alone would not do good; there needs to be scrutiny on what went wrong and a viable road map for the banks to exit PCA,” said Abizer Diwanji, partner and national leader-financial services, EY India. In effect, he is advocating that banks under distress be treated differently so that an effective rescue plan can be worked out.

For this to work, one of the most important exceptions to make would be of ownership and control, he added. Recent events at LVB and Dhanlaxmi Bank showed how a small segment of shareholders could sway the composition of the board and ensure the exit of a CEO. In LVB, less than 40 per cent of its shareholders, largely non-retail, appeared to have voted in concert to evict seven board members including its MD & CEO. In Dhanlaxmi Bank, the RBI-appointed MD & CEO Sunil Gurbaxani fell prey to collective shareholder action.

“There is enough evidence that diversified shareholding is a myth,” said a former RBI executive, who went on to perform multiple roles in the financial sector including as a retail banking chief, adding, “There are shareholders with vested interest who find ways to get their ends met.”

Her view is supported by B Ramesh Babu, who recently assumed charge as MD & CEO of Tamil Nadu-based Karur Vysya Bank. He bats for large institutional investors taking charge of banks in the interests of transparency. “They deal with many other banks and could share these best practices,” he said. But to do so, he urges shareholders who hold 5 to 10 per cent stakes to be more open to allowing institutional participation.

The RBI hasn’t imposed a merger on LVB so far — as was done, say, with Global Trust Bank with Oriental Bank of Commerce in 2004 — indicating its willingness to consider unconventional remedies, whether it is a large institutional investor taking a majority stake in the bank or its acquisition by a foreign bank subsidiary. Both options are well within the regulatory framework and make sense when diverse ownership has failed to do these banks much good. More importantly, there’s a precedent for both.

LVB and Clix Capital are exploring a merger. If negotiations progress and the deal gets RBI’s approval, it would be the second instance of a large private equity player (US-based Apollo Global Management in this case) taking control of an Indian bank. “As long as the investor goes through the RBI’s ‘fit and proper’ conditions and is willing to take a long-term view, the RBI should allow an investor to hold a larger equity share under a special dispensation scheme, and pare it down in a time-bound manner,” said Kuntal Sur, partner and leader, Financial Risk and Regulations, PwC.

This option was first explored by Canadian billionaire Prem Watsa in 2018 when his investment arm, Fairfax Financial, took a 51 per cent stake in Catholic Syrian Bank (now CSB Bank). Fairfax’s money has enabled CSB Bank to clean up its books, induct capable talent and even chart a diversification strategy. “Allowing a single promoter to take majority stake and giving it some years to reduce its stake will help build value over time,” said V Nagappan, a veteran investor in south India.

Another example of a PE-led turnaround is RBL Bank (formerly Ratnakar Bank) in 2010. Vishwavir Ahuja, its MD and CEO, and his team from Bank of America and other senior executives from foreign banks, including Citibank, and a clutch of PE investors — the regulatory thought process then was strongly in favour of diverse shareholding — helped the bank reinvent itself from an old private bank catering to Maharashtra’s sugar mill community to a new-age technology-driven outfit.

The foreign buyout-and-exit route has proven successful in the past. In 2002, the Netherlands-based ING Group acquired Vysya Bank, a small community-centric private bank. After nearly 12 years, ING decided to exit banking operations in India and ING Vysya was acquired by Kotak Mahindra Bank. “If not for 2008’s crisis, ING Vysya would have been a fantastic turnaround example,” said an industry observer.

One suggestion is that foreign banks operating as subsidiaries in India could be good targets for such mergers. “RBI could allow foreign banks operating as wholly-owned subsidiaries such as DBS India to bid for Indian private banks. This may incentivise global majors such as HSBC and Citibank to consider the same model,” said PwC’s Sur.

But the former RBI executive quoted above said foreign subsidiaries must first be allowed to split their operations to pursue such transactions. “Acquiring an Indian bank would be meaningful only for the foreign bank’s consumer business. If its entire capital is to be locked up in a merger, it doesn’t make sense,” she explained.

Crisis of capital has always been a problem for banks, more so in the last three years. For IDBI Bank (which was converted from public to private bank recently) or YES Bank, strong domestic investors — Life Insurance Corporation of India and State Bank of India — were brought in to infuse confidence capital. The regulator’s intent in both cases was to work out a solution within the existing framework and not compromise their identities.

Considering that old private banks’ capital requirements are far smaller, extending a similar solution would be helpful. With virtually no capital, LVB needs help fast, though it has a suitor knocking at the door. Dhanlaxmi Bank is showing the first signs of crisis. Balance sheets of other old private banks are scarcely in the pink. An early intervention and making exceptions on the shareholding norms could save the system from a similar crisis.

T E Narasimhan contributed to this article

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)