This story has been modified to rectify an error in the earlier version.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Deputy Governor Viral Acharya on Thursday said while there were several options on the table to recapitalise banks and address the resolution process, they were moving at a glacial pace and there was a lack of a “clear and concrete plan” to restore the health of public sector banks (RBI).

Indeed, “the lack of a clear and concrete plan for restoring public sector bank health,” remained an unfinished part of the RBI’s agenda, and also its “Achilles heel,” Acharya said.

It could be time to formulate a stronger plan, which Acharya termed “Sudarshan Chakra”, instead of the “Indradhanush” that the government is engaged in. Under Indradhanush, the government has committed to infuse more than Rs 70,000 crore in PSBs over four years, based on the performance of these banks. But, high bad debt on banks’ books have rendered the capital infusion plan inadequate. Already, the central bank requires high provisions for cases referred under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), but these provisions would rise sharply if companies go in for liquidation.

The RBI directed banks to file insolvency applications against 12 large accounts comprising about 25 per cent of the total non-performing assets (NPAs).

"The Reserve Bank has now advised banks to resolve some of the other accounts by December 2017; if banks fail to put in place a viable resolution plan within the timelines, these cases also will be referred for resolution under the IBC," Acharya said.

The need of the hour, he said, was to resolve the bad loans issue on banks’ balance sheets, which was close to ~8 lakh crore at the end of June.

“Having embarked on the NPA (non-performing assets) resolution process, indeed having catalysed the likely haircuts on banks, can we delay the bank resolution process any further?” Acharya asked in his speech at the 8th R K Talwar Memorial Lecture in Mumbai.

Without offering any direct solution to the problem, Acharya, who once favoured creating public asset reconstruction companies, posed a few questions.

“Can we articulate a feasible plan to address the massive recapitalisation needs of banks and publicly announce this plan to provide clarity to investors and restore confidence in the markets about our banking system?” he said, asking why banks were not raising capital from the equity markets at a time when liquidity chasing stock markets was plentiful. “What are the bank chairmen waiting for, the elusive improvement in market-to-book which will happen only with a better capital structure and could get impaired by further growth shocks to the economy in the meantime?” Acharya asked.

Further, he seemed to suggest the government could divest its stakes in banks quite aggressively to its minimum ownership level. “Can the government divest its stakes in public sector banks right away, to 52 per cent? And, for banks whose losses are so large that divestment to 52 per cent won’t suffice, how do we tackle the issue?”

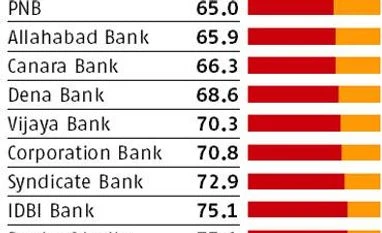

As of June 2017, the government held 57.1 per cent in State Bank of India, the lowest that it holds in all PSBs. In United Bank of India, the government’s share is as high as 85.2 per cent. The latter is under the RBI’s watch and is going through prompt corrective action, which curtails a bank’s normal activities.

Overall, in nine banks, government’s ownership is less than 70 per cent of the shares outstanding. But, in 11 banks, including IDBI Bank (75.1 per cent), which the government is trying to privatise to a great extent, the government’s stake is above 70 per cent. Many of these banks have heavy bad assets problems, but the government has been parsimonious in giving capital to these banks.

Acharya also perused the possibility of selling off the "valuable and sizable deposit franchises" to private capital providers, which means selling the branch network from where deposits are raised to private parties, and suggested that smaller banks should be taken as a test case for this.

“These questions keep me awake at nights. I fear time is running out,” Acharya said.

“The Indradhanush was a good plan, but to end the Indian story differently, we need soon a much more powerful plan — Sudarshan Chakra — aimed at swiftly, within months if not weeks, for restoring public sector bank health, in current ownership structure or otherwise,” he said.

The primary cause of the recent slowdown in growth has been the stress on banks’ balance sheets, Acharya said, adding: “… under-capitalised banks have capital only to survive, not to grow; those banks barely meeting the capital requirements will want to generate capital quickly, focusing on high-interest margins at the cost of high loan volumes”.

The IBC will address much of the stress on banks’ balance sheets by time-bound resolution. Acharya admitted that in the absence of the bankruptcy code, “the final outcomes have not been too satisfactory,” of the resolution schemes introduced by the RBI.

“The schemes were cherry-picked by banks to keep loan-loss provisions low rather than to resolve stressed assets,” he said.

The deputy governor also said the central bank’s internal committee on improving monetary policy transmission will be finishing its report by the last week of September.

However, if the resolution is not effective, it effectively prevents the banks from passing on rate benefits to their customers.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)