When James Hyman was a scriptwriter at MTV Europe, in the 1990s, before the rise of the internet, there was a practical — as well as compulsive — reason he amassed an enormous collection of magazines. “If you’re interviewing David Bowie, you don’t want to be like, ‘OK, mate, what’s your favourite colour?’,” he said. “You want to go through all the magazines and be able to say, ‘Talk about when you did the Nazi salute at Paddington Station in 1976.’ You want to be like a lawyer when he preps his case.”

Whenever possible, Hyman tried to keep two copies of each magazine he acquired. One pristine copy was for his nascent magazine collection and another was for general circulation among his colleagues, marked with his name to ensure it found its way back to him. The magazines he used to research features on musicians and bands formed the early core of what became the Hyman Archive, which now contains approximately 160,000 magazines, most of which are not digitally archived or anywhere on the internet.

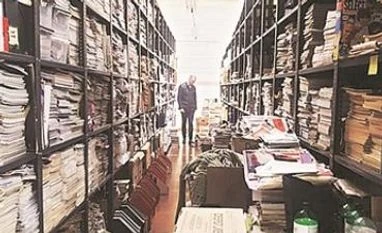

It was frigid inside the archive during a recent visit — a good 10 degrees colder than the chilly air outside — and the staff were bundled up. Space heaters illuminated a nest that Tory Turk (the creative lead), Alexia Marmara (the editorial lead) and Hyman had made for themselves amid boxes of donations to the collection. It lines more than 3,000 feet of shelving in a former cannon foundry in the 18th-century Royal Arsenal complex in Woolwich, a suburban neighbourhood abutting the Thames in southeast London.

The Hyman Archive was confirmed as the largest collection of magazines in 2012 by Guinness World Records; then, it had just 50,953 magazines, 2,312 of them unique titles. Now, a year and a half after Hyman was interviewed by BBC Radio 4, donations are pouring in, and amid them Hyman and his staff have carved out space for an armchair and a snack-laden desk. (The rest of the foundry is a storage facility used mostly by media companies to house their film archives and the obsolete technology with which they were made.)

At a moment when the old titans like Conde Nast and Time are contracting, shape-shifting and anxiously hashtagging, herein lies a museum of real magazine making, testament to the old glossy solidity. The price of admission, however, is stiff: visitors can do research with a staffer’s aid for £75 per hour (about $100), with negotiable day rates (and a student discount of 20 per cent), or gingerly borrow a magazine for three working days for £50. “I always knew it was a cultural resource and that there was value in it,” Hyman said of the archive. But having the collection verified by Guinness was about validation, he said, “because then people might take it more seriously than just thinking: ‘Some lunatic’s got a warehouse full of magazines.’”

Turk has a knack for repackaging Hyman’s animated monologues into what in the trade are called sound bites. “I maintain that James always had the foresight that this was going to be something else, more than just a sort of collector’s dream,” she said. “The archive is all about preserving and documenting the history of print.”

Hyman has kept magazines in various storage spaces since the late ‘80s, and had many, many magazines at home, in his spare room. But in 2010 his wife was expecting a baby. “I wasn’t given any ultimatums,” he said, “but it was like, ‘You’re going to have to sort this out.’” (At that time, Turk also helped Hyman pare down his collection of about 40,000 compact discs, like a scene out of the Nick Hornby novel “High Fidelity.”)

From 2012 the magazines sat nearly untouched in storage, including at an idle meat factory in Islington, during which time Hyman said he acquired another 30,000 to 40,000 magazines. Some 90,000 were shelved in alphabetical order at Cannon House in 2015, but the collection is too big to shift when, say, they get a set of 60 rare Playboys or a camper van full of issues of Athletics Weekly from the 1970s, as they recently did. Instead, another area of the archive is dedicated to magazines that have been acquired since the move.

The archive is still peppered with periodicals from the MTV days, marked “James.” To illustrate the point, Hyman, 47, pulled from the shelves a 1995 issue of the defunct FactSheet5 — “The definitive guide to the zine revolution” — with his name scrawled on the cover in black marker. After all these years, Hyman is still intimately familiar with its contents. “This is a phenomenal publication. It listed zines, just a quirky catalogue that reviewed fringe zines. It was sick,” he said, before seeking out and indicating a surprisingly positive review of a zine dedicated entirely to its founder’s genitals.

Each member of the team has a particular familiarity with the archive’s contents and has an institutional knowledge of certain titles and their whereabouts.

© 2018 The New York Times

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)