Self-driving cars will change how we live, in all sorts of ways. But they won’t just affect us humans – the coming revolution in autonomous transport has significant implications for wildlife as well. Nature conservationists and planners need to think hard about the impact of driverless vehicles, most notably in terms of renewed urban sprawl.

In some ways, wider developments in automotive technology bode well for the environment. Electric cars will increasingly replace the internal combustion engine, and that should, in theory, reduce carbon emissions and health-afflicting air pollution.

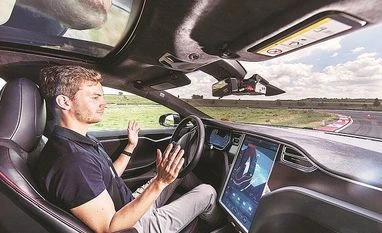

Through minimising traffic jams, driverless cars may also reduce overall energy use. Unlike human drivers, computers can avoid the “concertina” effect of needless acceleration and braking that exacerbates congestion, and won’t be tempted to “rubberneck” when passing an accident. And, as autonomous vehicles aren’t restricted by human reaction times, it may make sense to increase speed limits for them on major inter-city routes.

So driverless cars promise a future of faster journey times with much reduced environmental impacts. They may even mean less wildlife roadkill. But it’s the very efficiency of driverless cars that poses a challenge for planners and conservationists. The threat is an unchecked increase in low-density urbanisation.

Driving into the countryside

Autonomous vehicles promise a future in which passengers are free to use their time productively (working, for example). And they can park themselves (or be part of a shared pool) which saves yet more time in the morning rush. Coupled with faster journey times, the incentives to live further out of town will increase significantly.

There are both push and pull factors at work here: sky-high residential prices in most cities push people away from urban centres while healthy environments and green living pull people towards the hinterlands. The limiting factor in suburban spread is often travel time, either by public or private means. Driverless cars fundamentally alter the equation.

Existing planning policies are based on our current transport systems. Green-belts, for example, are designed to reduce urban sprawl by restricting development within a buffer zone around an urban area. However, the reduced transport times offered by driverless cars make it easier to live outside the belt while still working inside. So these loops of green are in danger of becoming a thin layer in a sandwich of ever-spreading suburbanisation.

This is, of course, a familiar challenge since the rise of the automotive age in the 1940s. However, the solutions designed by planners have been calibrated for a human-driving automotive system – not for the supercharged future of driverless transport.

Other examples of planning protection for wildlife include nature reserves, national parks and (in the UK) “Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty”. Such areas have either strict controls on development, or do not permit it at all. However, they are nice places to live in or nearby. The coming revolution in automotive journey times and the ability to work behind the (computer-driven) wheel will make living in such areas increasingly compatible with a commute to the nearest city.

Sick of sprawl

Natural habitats being lost entirely or splintered into ever-smaller fragments have long been understood as some of the primary causes of species extinctions across the world. Renewed urban sprawl threatens to increase the magnitude of both habitat loss and fragmentation. These threats are well known among conservationists, but there are differences of opinion on how best to respond.

For example, eco-modernists advocate a strategy of “land-sparing”, whereby human activities are concentrated into urban areas and vast tracts of land are set aside for nature. There are many cultural and ethical problems inherent in herding humans into cities, but the near-term planning issues posed by autonomous vehicles will exacerbate the challenge given they will boost demand to live in “unspared” lands.

Alternatively, some conservationists advocate “land-sharing”, in which human communities redesign the way we farm and live so as to co-exist with wildlife, cheek-by-jowl. Autonomous vehicles pose significant challenges for either approach, by supercharging the fragmentary effect of road systems.

Whichever approach is taken, we’ll need to redesign existing systems and policies to take account of the increased range that driverless transport facilitates. This may involve new zoning laws to protect wider areas of countryside than at present. It certainly requires further development of green infrastructure, habitat corridors and “greenways”.

It might also involve engineering solutions, especially given the fact that autonomous vehicles should be much more amenable to being driven underground. It is possible to imagine a future in which the famous bear bridges of Banff are tiny precursors to a vast programme in which rural highways are covered with forests of green. Retro-fitting roads into tunnels won’t be cheap, but it becomes easier when human drivers are taken out of the equation. Software drivers are less bothered by artificial light and more efficient at mitigating the congestion impact during construction.

Dr Timothy Hodgetts, Research Fellow in the Geopolitics of Wildlife Conservation, University of Oxford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)