For years, mergers and acquisitions in technology were fairly straightforward: Every investment bank kept a list of a dozen or so companies like Google and IBM that had a track record of acquisitions and cash to deploy. When the time and price were right, bankers would seek to match the tech giants with a start-up, and a deal would be hatched.

Now the technology deal-making club has had its doors blown wide open.

All kinds of companies, including century-old industrial stalwarts like General Motors and General Electric, are among the corporate giants acquiring tech start-ups of late.

This trend, of course, reflects how new technology is radically changing many traditional businesses. Developments like connected homes and driverless cars are upending old models.

Many companies have come to the realisation that building technology in-house was a painstaking process that often meant getting leapfrogged by start-ups.

So companies not usually thought of as being in the tech sector have become more aggressive, making more than

$125 billion worth of acquisitions in 2016, the most ever. Five years ago, that figure was $20 billion.

“There’s no doubt that many non-tech companies have tried to build and have made the determination that it’s enormously challenging,” said Anthony Armstrong, co-head of technology mergers and acquisitions at Morgan Stanley. “It’s better to acquire disruptive technology than to be disrupted by that technology.”

The examples span many industries. Walmart purchased the e-commerce start-up Jet.com, while General Electric agreed to buy ServiceMax, whose software provides information about off-site workers and equipment repairs. Roper Technologies, another century-old industrial conglomerate, signed a deal with Deltek, an enterprise-software provider. Automakers such as General Motors and Daimler have taken large stakes in ride-sharing applications, including Lyft and Hailo.

Last year, the number of technology companies sold to non-tech companies surpassed those acquired by tech companies for the first time since the internet era began, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Excluding private equity buyers, 682 tech companies were purchased by a company in an industry other than technology, while 655 were acquired by tech companies, Bloomberg’s data showed. More broadly, merger activity was down in 2016.

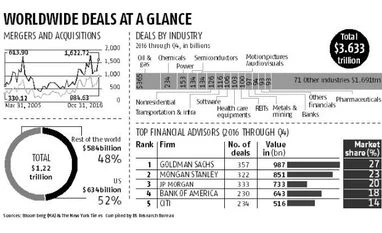

Companies around the world announced $3.6 trillion worth of deals last year, a decline of 16.6 percent from 2015, which was a record year, according to data compiled by Thomson Reuters.

The number of deals signed rose slightly from 2015, the data showed.

Of the 45,416 transactions announced last year, 6,657, or 15%, were acquisitions of technology companies, more than any other sector, according to data compiled by Thomson Reuters on Thursday. That was in line with the proportion of technology deals in 2015.

Still, many of tech’s big traditional buyers were quiet last year. Four of the five largest tech companies by market capitalization did not announce any giant deals in 2016.

Among the major deals that were signed were Qualcomm’s $39 billion purchase of NXP Semiconductors, Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn for $26 billion and Oracle’s $9.3 billion deal with NetSuite. IBM, Google and Facebook made a few small acquisitions, but nothing material. Investment bankers expect this trend to continue this year as well. They have been fielding many calls from companies outside the tech sector wondering what shareholders might think about a potential tech acquisition.

Non-tech chief executives have been found mingling at technology conferences, trying to spot their next potential target. And the assortment of so-called unicorns, or private companies valued at $1 billion or more, may be more inclined to sell this year after very few went public or sold in 2016.

Only 20 technology companies went public last year, the fewest since 2009, according to Thomson Reuters. With almost 200 unicorns, there could be more exits this year if the markets hold up. One major shift as to why non-tech executives are becoming more active in tech deal making is that they have become more comfortable with the technology itself.

“Very rarely are management teams willing to get into businesses that they absolutely don’t understand,” said Scott Adelson, co-president and global co-head of corporate finance at Houlihan Lokey. “Software and internet are so pervasive that it’s no longer something that the average management team can’t wrap their head around.”

Some companies are also trying to recast themselves as tech companies.

General Electric has moved its headquarters to Boston, more of a hub for tech and start-ups than its previous home in Fairfield, Conn. The company’s recent commercials feature the tagline: “The digital company. That’s also an industrial company.”

Honeywell’s incoming chief executive, Darius Adamczyk, was formerly the head of a technology company that Honeywell acquired eight years ago. He has a bachelor’s degree in electrical and computer engineering, and a master’s degree in computer engineering.

Companies like the health insurance provider UnitedHealth Group; Northrop Grumman, a defense contractor; and Macy’s were among those with the most listings for tech-related jobs over the last month, according to Monster.com. (Acquiring talented engineers is another reason non-tech companies seek to buy tech companies.)

Historically, non-tech companies have largely not felt comfortable paying the high prices that many tech companies can fetch. Older, mature companies tend to trade at lower valuations relative to measures like revenue and earnings, compared with young technology companies — which sometimes do not even have earnings.

“When it comes to M.&A., boards and C.E.O.s of non-tech companies have become much more fluent in the language of tech company valuations,” Mr. Armstrong of Morgan Stanley said.

The next challenge for many of these companies might be in integrating their tech start-ups with the main business.

When traditional companies acquired small technology companies, they typically would place them in a “digital division” separate from the rest of the company.

That too needs to change, according to Aryeh Bourkoff, the founder and chief executive of the investment bank LionTree.

“Technology should not be a division of a company. It should be integrated into every division,” he said.

For now, investors in traditional companies seem willing to let these companies make bets and take risks because they too know the stakes of disruption are high.

“Shareholders are judging management teams on their ability to be bold and not just make short-term moves,” Mr. Bourkoff said. “The bold C.E.O.s are the ones that play to the future.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)