They call it the “Church Lane Hug.”

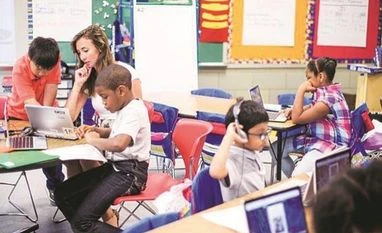

That is how educators at Church Lane Elementary Technology, a public school here, describe the protective two-armed way they teach students to carry their school-issued laptops.

Administrators at Baltimore County Public Schools, the 25th-largest public school system in the United States, have embraced the laptops as well, as part of one of the nation’s most ambitious classroom technology makeovers. In 2014, the district committed more than $200 million for HP laptops, and it is spending millions of dollars on math, science and language software. Its vendors visit classrooms. Some schoolchildren have been featured in tech-company promotional videos.

And Silicon Valley has embraced the school district right back.

HP has promoted the district as a model to follow in places as diverse as New York City and Rwanda. Daly Computers, which supplied the HP laptops, donated $30,000 this year to the district’s education foundation. Baltimore County schools’ top officials have traveled widely to industry-funded education events, with travel sometimes paid for by industry-sponsored groups.

Silicon Valley is going all out to own America’s school computer-and-software market, projected to reach $21 billion in sales by 2020. An industry has grown up around courting public-school decision makers, and tech companies are using a sophisticated playbook to reach them, The New York Times has found in a review of thousands of pages of Baltimore County school documents and in interviews with dozens of school officials, researchers, teachers, tech executives and parents.

School leaders have become so central to sales that a few private firms will now, for fees that can climb into the tens of thousands of dollars, arrange meetings for vendors with school officials, on some occasions paying superintendents as consultants. Tech-backed organizations have also flown superintendents to conferences at resorts. And school leaders have evangelized company products to other districts.

These marketing approaches are legal. But there is little rigorous evidence so far to indicate that using computers in class improves educational results. Even so, schools nationwide are convinced enough to have adopted them in hopes of preparing students for the new economy.

In some significant ways, the industry’s efforts to push laptops and apps in schools resemble influence techniques pioneered by drug makers. The pharmaceutical industry has long cultivated physicians as experts and financed organizations, like patient advocacy groups, to promote its products.

Studies have found that strategies like these work, and even a free $20 meal from a drug maker can influence a doctor’s prescribing practices. That is one reason the government today maintains a database of drug maker payments, including meals, to many physicians.

Tech companies have not gone as far as drug companies, which have regularly paid doctors to give speeches. But industry practices, like flying school officials to speak at events and taking school leaders to steak and sushi restaurants, merit examination, some experts say.

“If benefits are flowing in both directions, with payments from schools to vendors,” said Rob Reich, a political-science professor at Stanford University, “and dinner and travel going to the school leaders, it’s a pay-for-play arrangement.”

Close ties between school districts and their tech vendors can be seen nationwide. But the scale of Baltimore County schools’ digital conversion makes the district a case study in industry relationships. Last fall, the district hosted the League of Innovative Schools, a network of tech-friendly superintendents. Dozens of visiting superintendents toured schools together with vendors like Apple, HP and Lego Education, a division of the toy company.

The superintendents’ league is run by Digital Promise, a nonprofit that promotes technology in schools. It charges $25,000 annually for corporate sponsorships that enable the companies to attend the superintendent meetings. Lego, a sponsor of the Baltimore County meeting, gave a 30-minute pitch, handing out little yellow blocks so the superintendents could build palm-size Lego ducks.

Karen Cator, the chief executive of Digital Promise, said it was important for schools and industry to work together. “We want a healthy, void-of-conflict-of-interest relationship between people who create products for education and their customers,” she said. “The reason is so that companies can create the best possible products to meet the needs of schools.”

Several parents said they were troubled by school officials’ getting close to the companies seeking their business. Dr. Cynthia M. Boyd, a practicing geriatrician and professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine with children in district schools, said it reminded her of drug makers’ promoting their medicines in hospitals.

“You don’t have to be paid by Big Pharma, or Big Ed Tech, to be influenced,” Dr. Boyd said. She has raised concerns about the tech initiative at school board meetings.

A makeover is born

Baltimore County’s 173 schools span a 600-square-mile horseshoe around the city of Baltimore, which has a separate school system. Like many districts, the school system struggles to keep facilities up-to-date. Some of its 113,000 students attend spacious new schools. Some older schools, though, are overcrowded, requiring trailers as overflow classrooms. In some, tap water runs brown. And, in budget documents, the district said it lacked the “dedicated resources” for students with disabilities.

In a district riven by disparities, Dallas Dance, the superintendent from 2012 through this past summer, made an appealing argument for a tech makeover. To help students develop new-economy skills, he said, every school must provide an equitable digital learning environment — including giving every student the same device.

“Why does a first grader need to have it?” Mr. Dance said in an interview last year. “In order to break the silos of equity, you’ve got to say that everyone gets it.”

The district wanted a device that would work both for youngsters who couldn’t yet type and for high schoolers. In early 2014, it chose a particularly complex machine, an HP laptop that converts to a tablet. That device ranked third out of four devices the district considered, according to the district’s hardware evaluation forms, which The Times obtained. Overall, the HP device scored 27 on a 46-point scale. A Dell device ranked first at 34.

The district ultimately awarded a $205 million, multiyear contract to Daly Computers, a Maryland reseller, to furnish the device, called the Elitebook Revolve.

Mychael Dickerson, a school district spokesman, said, “The device chosen was the one that was closely aligned to what was recommended by stakeholders.” Daly did not respond to inquiries.

With the laptop deal sealed, Silicon Valley kicked into gear.

In September 2014, shortly after the first schools received laptops, HP invited the superintendent to give a keynote speech at a major education conference in New York City. Soon after, Gus Schmedlen, HP’s vice president for worldwide education, described the event at a school board meeting.

“We had to pick one group, one group to present what was the best education technology plan in the world for the last academic year,” Mr. Schmedlen said. “And guess whose it was? Baltimore County Public Schools!”

An HP spokesman said the company did not pay for the trip. He said the company does not provide “compensation, meals, travel or other perks to school administrators or any other public sector officials.”

The superintendent later appeared in an HP video. “We are going to continue needing a thought partner like HP to say what’s working and what’s not working,” he said.

Microsoft, whose Windows software runs the laptops, named the district a Microsoft Showcase school system. Intel, whose chips power the laptops, gave Ryan Imbriale, the executive director of the district’s department of innovative learning, an Intel Education Visionary award.

Recently, parents and teachers have reported problems with the HP devices, including batteries falling out and keyboard tiles becoming detached. HP has discontinued the Elitebook Revolve.

Mr. Dickerson, the district spokesman, said there was not “a widespread issue with damaged devices.”

An HP spokesman said: “While the Revolve is no longer on the market, it would be factually inaccurate to suggest that’s related to product quality.”

Asked what device would eventually replace the Revolve in the schools, the district said it was asking vendors for proposals.

Mr. Dance’s technology makeover is now in the hands of an interim superintendent, Verletta White. In April Mr. Dance announced his resignation, without citing a reason. Ms. White has indicated that she will continue the tech initiative while increasing a focus on literacy.

A Baltimore County school board member, David Uhlfelder, said a representative from the Office of the Maryland State Prosecutor had interviewed him in September about Mr. Dance’s relationship with a former school vendor (a company not in the tech industry).

The prosecutor’s office declined to confirm or deny its interest in Mr. Dance.

Mr. Dance, who discussed the district’s tech initiatives with a Times reporter last year, did not respond to repeated emails and phone calls this week seeking comment.

©2017 The New York Times News Service

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)