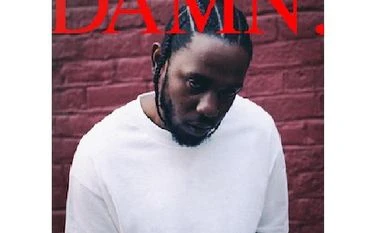

A year ago, shock waves rippled through the arts world when the Pulitzer Prize in Music, almost always bestowed on a classical composer, was awarded to Kendrick Lamar’s album “DAMN.”

“This is a big moment for hip-hop music and a big moment for the Pulitzers,” Dana Canedy, the prizes’ administrator, said then. “I never thought I’d be a part of it,” Mr Lamar told Vanity Fair about the prize. “It’s one of those things that should have happened with hip-hop a long time ago.”

It was not only the first time the prize had gone to a hip-hop work; never before had it been given to any kind of mainstream popular music. Even as Pulitzer-winning musical styles shifted over the decades, from the Americana of Copland’s “Appalachian Spring”(1945) to the fragmented atonality of Donald Martino’s “Notturno”(1974) to the joyful genre-bending of Caroline Shaw’s “Partita” (2013), the prize has remained almost exclusively the province of classical music.

But Mr Lamar’s Pulitzer upended all that. Was “DAMN.” a fluke, or will the prize — the 2019 winner will be announced on April 15 — genuinely embrace popular music? What now counts as a “distinguished American composition”? The music Pulitzer was established in 1943 as a celebration of homegrown art in the midst of World War II; the first winner was a briskly patriotic cantata by the Neo-Classicist William Schuman. For decades, the prize was mostly given to well-established composers: As Mr Martino once said, “If you write music long enough, sooner or later someone is going to take pity on you and give you the damn thing.”

Recently the prize has broadened in aesthetic scope and given a career boost to young composers like Ms. Shaw, who was 30 when she won. But until Mr Lamar, it had still barely budged outside of its old classical music limits.

Even Mr Lamar’s path to victory last year was somewhat unusual: “DAMN.” had not been officially submitted. But during a weekend of deliberations, the five-member music jury weighed the merits of some classical submissions that drew on hip-hop influences, and came to the conclusion that hip-hop itself should be under consideration.

The jury introduced “DAMN.” into the process and ultimately decided it was worthy of the prize. “We’re there all day listening, reading, discussing,” one of the 2018 jurors, the jazz violinist Regina Carter, said in a recent interview. “We were all really respectful of one another and listened to each other. There was no fighting going on: We’d argue our cases, but it never got ugly.”

But even if SoundCloud rappers and aspiring singer-songwriters start to submit, their work still needs to be evaluated by a jury. Pulitzer juries in the past decade have typically comprised a mix of classical and jazz musicians, critics, academics and arts administrators. Will future juries give adequate attention to nonclassical submissions — or have the knowledge to properly distinguish a work of the caliber of “DAMN.” from other hip-hop entries?

The prize, moreover, is not actually decided by the music jurors. The jury is instructed to provide the Pulitzers’ administrative board — which includes journalists, editors and academics, but not professional musicians — with three unranked nominations. The board then decides which of the three receives the award. Last year’s Pulitzer could well have gone to one of the other, more conventional finalists, the composers Ted Hearne and Michael Gilbertson, rather than Lamar.

And if a future board were to be confronted with, say, an opera by Tania León, an experimental record by Nicole Mitchell, and a visual album by Beyoncé, might its members tend to select the finalist with whom they were already most familiar? “That’s just never happened,” Ms Canedy said. “Every finalist gets its due when it comes before the board,” she added. “They do what they do, which is download the work, listen to it, debate it, and then make a decision.”

It’s not always that simple. In 1992, the music jury recommended only a single finalist: a work by the composer Ralph Shapey. The board demanded the jury provide a second option and, when a piece by the composer Wayne Peterson was submitted, the board chose the Peterson.

Angry jurors then released a statement describing the board’s decision as “especially alarming because it occurred without consultation and without knowledge of either our standards or rationale. Such alterations by a committee without professional musical expertise guarantees, if continued, a lamentable devaluation of this uniquely important award.”

And the Pulitzer remains singularly important — which makes its intricate rules and shifts of stylistic emphasis big news in the music world. The 2019 prize may go to a groundbreaking symphony, a confessional folk record or a transcendent mixtape. Speaking in late February, Ms Canedy said that the music jury — which will remain anonymous until the prize is announced — had selected three finalists.

“We had a diverse slate of entries,” she said. “We have three finalists that we’re incredibly proud of, and would be happy to see any of the three win a Pulitzer.”

©2019TheNewYorkTimesNewsService

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)