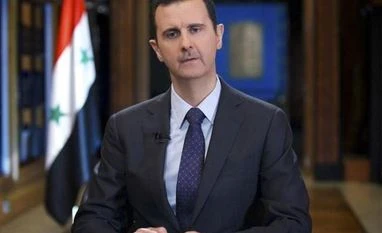

Entire cities lie in ruins, the economy is collapsing and more than half the population has been displaced, but Bashar al-Assad has emerged as the last man standing from Syria’s decade of war, having played off friend and foe to restore his grip over most of the country.

In power since 2000, Assad’s poised to win a fourth seven-year term in Wednesday’s presidential elections. Though the vote’s been roundly dismissed by the U.S. and European nations as a sham, the Syrian leader’s been bolstered by moves to woo him back into the Arab fold, part of a broader realignment that’s seen Saudi Arabia work to ease tensions with Iran and tamp down conflicts across the Middle East.

Wide-ranging Western sanctions on Syria mean Gulf countries are unlikely to invest significantly in reconstruction that’s likely to cost $120 billion or more, at least for now, but even a diplomatic rapprochement would mark a remarkable shift in regional faultlines that once saw Iran and Saudi Arabia engaged in proxy conflicts from Syria, to Lebanon to Yemen.

The Biden administration is focused on reviving the 2015 nuclear pact with Tehran, which was abandoned under Donald Trump, and isn’t keen to inflame tensions over Syria, where the Iranians and their Lebanese proxy Hezbollah were instrumental in propping up Assad, according to two people familiar with the matter. It’s said it wouldn’t recognize the results of elections not held under UN supervision and, like European allies, will maintain strict sanctions -- a policy that has yet to persuade Assad to share power.

Russia, whose military intervention helped pivot the war in Assad’s favor, has pushed Arab countries to rebuild their ties in an effort to imbue him with regional legitimacy and to check Iranian influence -- an unspoken rivalry the Syrian leader’s exploited to his advantage.

That’s left Arab leaders, who severed ties with Assad after the start of the uprising in 2011 and supported the rebels fighting against him, increasingly pondering whether it’s time to cut their losses, and even invite Syria back into the Arab League.

Saudi Outreach

When Saudi Arabia’s intelligence chief, Khalid al-Humaidan, met his counterpart in Damascus this month, he offered to restore relations and provide the government with financial aid through humanitarian channels in return for a split from Tehran, said a diplomat briefed on the talks.

The Syrians declined to abandon the Iranians, but kept the door open for further communications, two people who were briefed on the meeting said, calculating they’d eventually crack the isolation.

Saudi Arabia’s outreach, both in Damascus and Baghdad, where it’s held indirect talks with Iran to reduce tensions with Iranian-backed Yemeni rebels, has emboldened Assad, as well as Hezbollah, which have concluded that the shift in U.S policy under Biden has put Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on the back foot, the people said.

Saudi and Iraqi officials have confirmed contacts took place in Baghdad but have not acknowledged the Damascus meeting.

David Schenker, Trump’s assistant secretary of state for the Near East, said while the current U.S. administration was uncomfortable with Syria’s status quo, it would be a mistake to allow the rehabilitation of Assad thinking it would restore security.

“Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi want security, not war. They want a modus vivendi but the Iranians don’t appear to be interested. They’re happy to talk, to have more trade, more smuggling but they now dominate in Yemen, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq and from their point of view there’s no need for accommodation,” he said by telephone.

“Certainly, the nuclear threat is the greatest and has to be dealt with as a priority but if those other threats aren’t dealt with, it will not bring stability.”

A veneer of legitimacy

Syria’s civil war erupted when the Arab Spring protests of 2011 were met with repression, morphing into armed rebellion and chaos.

The regime sought to re-establish legitimacy with multi-party elections in 2014, but Assad won over 90% of the vote in an exercise widely dismissed as theater. Russia intervened the next year, unleashing devastating bombardment of rebel-held areas that allowed Assad to gradually regain his grip as international peace efforts foundered.

Only the northwestern province of Idlib remains under Turkish protection, home to a hodge-podge of Islamist and other fighters, while Kurdish groups retain a measure of autonomy in parts of the northeast, where there’s a residual U.S. presence from the international fight against Islamic State that’s currently under review.

The U.S. and European governments are asking Gulf countries not to normalize ties, say diplomats. But their reluctance to get too involved or to engage Assad have left the field open to Moscow which, with Ankara and Tehran, has shaped Syria’s post-war contours at their expense.

“Russia hopes that Arab countries, Gulf nations will change their position and help with reconstruction,” said Elena Suponina, a Moscow-based Middle East expert. “Russia will remain as a guarantor of stability in Syria. As per Iran’s role, it is hard to believe that Arab countries can buy Assad and make him cut ties with Assad. No. Assad will develop his relations with Arab monarchies and keep his ties with Iran.”

For Saudi Arabia, which supported Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear accord, Biden’s arrival changed the calculation. The world’s largest oil exporter has already been shaken by repeated attacks on its oil infrastructure mounted by Iranian-backed Yemeni rebels, driving it to seek a separate understanding to guarantee its security in a febrile region rather than counting on an old ally that’s often disappointed.

“Under the Biden administration, diplomatic engagement, even with controversial actors, is viewed as less problematic,” said Cinzia Bianco, a fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations who’s focused on the Gulf. “Saudi Arabia sees value in re-positioning itself as an actor that will not close the door to dialog and diplomacy.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)