The invasion of Ukraine is causing a mass exodus of companies from Russia, reversing three decades of investment by Western and other foreign businesses there following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The list of those cutting ties or reviewing their operations is growing by the hour as foreign governments ratchet up sanctions against Russia, close airspace to its aircraft and lock some banks out of the SWIFT money messaging system. With the ruble plunging and the U.S. banning transactions with the Russian central bank, operating in Russia has become deeply problematic. Some companies have concluded that the risks, both reputational and financial, are too great to continue.

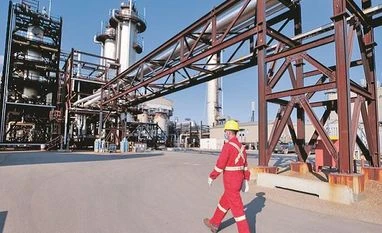

For some companies, the decision to exit Russia is the conclusion of decades of lucrative, if sometimes fraught, investments. Foreign energy majors have been pouring money in since the 1990s. Russia’s largest foreign investor, BP Plc, led the way with its surprising announcement on Sunday that it would exit its 20 per cent stake in state-controlled Rosneft, a move that could result in a $25 billion write-off and cut its global oil and gas production by a third.

The stake was the product of a protracted battle in 2012 for control over TNK-BP, a joint venture between the oil giant and a group of billionaires. It’s now weighing whether to sell its stake back to Rosneft, according to people familiar with the situation.

Shell Plc followed on Monday. Citing Russia’s “senseless act of military aggression,” it said it is ending partnerships with state-controlled Gazprom, including the Sakhalin-II liquefied natural gas facility and its involvement in the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project, which Germany blocked last week. Both projects are worth about $3 billion. Kwasi Kwarteng, the U.K. business secretary, met with Shell Chief Executive Officer Ben van Beurden on Monday to discuss the company’s involvement and welcomed the move.

“Shell have made the right call,” he tweeted. “There is now a strong moral imperative on British companies to isolate Russia. This invasion must be a strategic failure for Putin.”

Equinor ASA, which is Norway’s biggest energy company and majority owned by the state, also announced it will start withdrawing from its joint ventures in Russia, worth about $1.2 billion. “In the current situation, we regard our position as untenable,” CEO Anders Opedal said.

France’s TotalEnergies SE, which is involved in major liquefied natural gas projects in Russia, said it will no longer provide capital for new developments in the country, a modest concession to the mounting political pressure. Among other major energy companies, Exxon Mobil Corp. oversees the Sakhalin-1 project with Rosneft and companies from Japan and India.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if you see more announcements coming down the line about exits,” said Allen Good, sector strategist at Morningstar.

When the Soviet Union fell apart, foreign companies saw enormous opportunities – a massive new market of millions of consumers as well as minerals and oil – and poured in to buy, sell and partner with Russian firms.

With Russia’s invasion of neighbouring Ukraine, that trend has come to a screeching halt. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the largest in the world, said it’s freezing Russian assets worth about $2.8 billion and will come up with a plan to exit by March 15.

Banned From Soccer

In a move that will reverberate well beyond the business community, the world soccer body FIFA and the European authority UEFA banned Russian teams from games. “Football is fully united here and in full solidarity with all the people affected in Ukraine,” it said in a joint statement. The entertainment world has also reacted, with Sony Pictures suspending new movie releases in Russia, according to Nikkei, which cited a company statement.A boycott of one of Russia’s most iconic products, vodka, is also gathering steam, with at least three U.S. governors ordering the removal of Russian-made or branded spirits from stores. One of the largest alcohol chains in New Zealand pulled thousands of bottles of Russian vodka from stock — filling the empty shelves with Ukrainian flags.

Mark McNamee, Europe director at advisory firm FrontierView, was in Moscow two weeks ago talking to executives on the potential fallout of an invasion. Many shrugged off the worst scenarios, he said, which means they weren't necessarily prepared for what has transpired.

Many corporations will have a difficult time supporting local operations given the SWIFT ban and capital controls, he said. Firms in the energy or commodities sectors or those selling to the Russian government will face the potential risk of being perceived as "profiting from the war."

Consumer goods companies with extensive operations and local production in Russia can’t easily get out, even if they want to, but face financial turmoil. Before the invasion last week, Danone SA, which runs Russia’s largest dairy business and has been operating in Ukraine for more than 20 years, said it was putting additional plans in place to prepare for any military escalation.

Chief Financial Officer Juergen Esser said the company was trying to buy more local ingredients for its products from both markets, where the vast majority of raw materials are already domestically sourced. Danone entered the Russian market three decades ago. The country accounts for about 5% of the company’s net sales, and Ukraine less than 1%.

Carlsberg A/S is the largest brewer in Russia through its ownership of Baltika Breweries. The majority of Baltika's supply chain, production and customers are based in the country, which limits the direct impact of many sanctions, a Carlsberg spokeswomen said. The company has limited export from and imports to Russia, where Carlsberg employs 8,400 people, but it's currently not possible to estimate the full extent of the direct or indirect consequences from sanctions, she said. It employs 1,300 workers in Ukraine, where last week it halted operations at its breweries and sent workers home.

Foreign companies could face pushback from the Russian government, which could encourage boycotts or -- in an extreme case -- move to seize assets, McNamee said.

"If you have iconic brands from Italy, Germany, U.K. and America, you're ripe for retaliation by the Russian government," he said.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)