The German-born, New York based painter Michael Krebber is supported by a dream team of dealers and collectors.

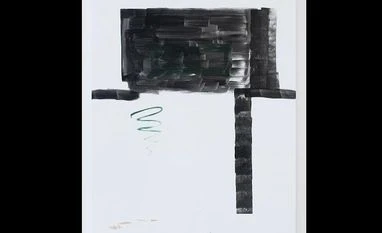

His work, which toys with art history by challenging perceptions of what a painting can look like (he’s painted text from webpages, made paintings that appear to be doodles, or unfinished), is represented by a list of galleries that reads like an Artforum Critics’ Picks checklist: Greene Naftali in New York, Chantal Crousel in Paris, Dépendance in Brussels, Galerie Buchholz, which has locations in Berlin, Cologne, and New York, and Maureen Paley in London.

His collector base, meanwhile, is prestigious, discreet, and fervent: “I find the group of collectors who buy his work are incredibly devoted,” says the adviser Eleanor Cayre, who collects Krebber’s art. “This group only seems to be getting larger and larger, particularly now as we’re seeing many museums and institutions joining the fray.”

Despite that pedigree, Krebber has remained surprisingly under-the-radar, a virtual unknown to those in the broader art world, let alone the mainstream public.

“He’s a significant artist, and he falls into a category that’s typically called “painters’ painters,” says art adviser Allan Schwartzman, who’s placed Krebber’s art with numerous clients. “That means a painter who’s revered by other painters but barely known to collectors.”

There are signs that this is about to change. This year, a significant exhibition of Krebber’s work travelled from the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, Portugal, to the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland. A catalogue raisonné, which is a compilation of every work the artist has ever made, is currently in the works.

Most telling, after a sluggish couple of decades on the auction market, Krebber’s art — while still comparatively affordable compared to his peers’ million-dollar results — is beginning to inch upwards in price. (Currently, you can buy a painting of his for the tens of thousands and a drawing for under $10,000.)

“Ultimately, what takes an artist to the next level is the integrity and presence of the art they make,” says the dealer Carol Greene of Greene Naftali, whose gallery sold a work by Krebber for around $100,000 at Art Basel in Miami Beach earlier this month.

Krebber, who was born in Cologne, Germany, in 1954, studied painting at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karslruhe, Germany. He was an assistant in the studios of superstar German artists Martin Kippenberger and Georg Baselitz. (Krebber’s supporters often point to these affiliations, both as proof of his pedigree and to underscore the dramatic difference in their and Krebber’s prices.)

But unlike the aforementioned German painters, Krebber’s paintings and drawings are often minimal and occasionally inscrutable. A recent series that’s become highly sought-after is his so-called “Snail” set of paintings, which sometimes consist of only one line.

Starting in 2002, Krebber became a teacher at Frankfurt’s Städelschule (he left the position in 2016, when he moved to New York), in the process influencing a group of younger artists who have become, over time, devotees.

Influential as he might be, Krebber’s market, at least until recently, was a slow burn. His first painting to come to auction, according to Artnet, was Les bisch ja nich in Stich II, painted around 1992-1993. It came up to the block at Christie’s South Kensington in 1999 with an estimate of $2,000 to $3,000 and failed to find a buyer, as did a second work from the series that came up the the same day.

It took an additional decade for his next work to appear, when a watercolour sold at a small Swiss auction house for less than a thousand dollars. It wasn’t until 2012, when an untitled black-and-white painting sold for $10,181 at the Parisian auction house Artcurial, that one of Krebber’s works publicly broke the $10,000 mark.

His primary market was similarly sedate, mirroring, more or less, the auction market. But in the last five years, dealers say, things have begun to pick up. Paintings began popping up at auction and selling, with some regularity, well above estimate.

A 2014 sale at Christie’s New York saw a painting soar above its high estimate of $9,000 and sell for $52,500; the next year, a painting executed in 2000 had a high estimate of $40,000 and sold for $100,000; and the year after that, in 2016, a painting from 1997 carrying a high estimate of $112,000 sold for $237,296 at Sotheby’s in London.

On the primary market, dealers say, his work has been on a similar upward trend. Today, his drawings sell for $7,500, says Greene, and paintings range from $40,000 up to $250,000 for multi-panel paintings and installations. Orlowski says he’s sold Krebber paintings privately for $300,000.

The question, then, is what it will take to push those numbers even higher. Orlowski says that when the catalogue raisonné publishes it will “change the market.” The market of an artist, he says “is driven by masterpieces, and people don't realise yet how many masterpieces Krebber has made.”

Schwartzman has a more measured outlook. “He has all the signifiers of someone who’s undervalued,” he says. “But does it take one year for it to happen, or 15? I don’t know.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)