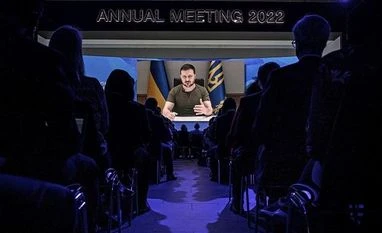

War in Ukraine, rampant inflation and now a brewing global food crisis. If attendees at this year’s World Economic Forum came to Davos worried, they left with little to comfort them.

As guests of the first in-person

WEF conference in two years prepare to head home, they do so increasingly concerned about the economic fallout from Russia’s invasion of its neighbor and signs that the conflict will run longer than they initially imagined.

While politicians, executives and investors vocally declared support for Ukraine’s resolve, those with money to make and shareholders to pacify privately hoped and assumed that a deal will eventually be struck with Russian President Vladimir Putin. But if anyone wants Ukraine to cede territory as part of a negotiation, that’s a no-go area for Kyiv.

The risk of a global recession -- a repeated topic at meetings -- was just one reason for wanting a ceasefire as the war enters its fourth month. Another was the inflation spike that’s sucking money out of workers’ pockets, leaving less for spending on what companies are making. And now there’s the mounting food emergency many failed to anticipate, exacerbating a humanitarian disaster in a world still getting over the Covid pandemic.

One delegate who would talk openly was Ryan Peterson, chief executive of Flexport, a trade logistics software company.

He said a deal to open Ukraine’s ports is needed to avoid “mass starvation” in the developing world as grain and fertilizer currently cannot be shipped through the war zone that is the Black Sea.

“The simple solution is that someone has got to deal with Putin, and that someone probably” is US President Joe Biden, he said. “The whole thing is how do we get the food out.”

Amid the condemnation of the blockade of Black Sea ports, Russia said late Wednesday it would open corridors to allow passage. But shipments may not begin quickly because of Ukraine’s concerns about security.

While an end to the war would guarantee a rebound in global growth by stemming the destruction of confidence and trade, the sinking feeling for the global titans is that they have little to no influence right now.

Both the war and the resulting food and energy crises are for political leaders to resolve. And there were fewer of those than usual making the trip this year to the Alpine conference. Partying in a ski resort with millionaire bankers and business executives may not be the ideal image during a cost-of-living crisis that’s deepening the divisions between the haves and the have-nots.

John Chipman, director-general of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, said politicians were giving the business community short shrift.

“On this tier one, triple-A, geopolitical argument, they will be treated as junk bonds by the politicians in terms the quality of their influence,” he said.

Global Emergency

While the food crisis emerged as one of the dominant topics, it’s taken political and business leaders by surprise. At Davos, where the WEF claims to be “committed to improving the state of the world,” that was evident in the fact that only one panel was devoted to the brewing international emergency.

Russia and Ukraine supply a quarter of the world’s wheat, and Belarus, which is also sanctioned, is the second largest exporter of potash fertilizers. Ukraine’s crop is stuck in silos on the Black Sea, land-mines have made parts of the country unfarmable and, in a bid for food security, multiple countries have export restrictions on food products.

Beata Javorcik, chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, described the situation as a “perfect storm,” and warned of a worse food shortage than between 2008 and 2011, when droughts and the global recession drove up food prices and led to riots in 14 countries, triggering the Arab Spring.

“This war has the potential to cause political instability around the world,” she said. “Why did no one see this coming? Because people did not expect the war to last this long. What is the possible solution? The question is, what would a peace settlement look like? Only now are people asking this question.”

Amid the threats and political fatigue, there are signs that political unity may be splintering. French President Emmanuel Macron has spoken about a peace settlement that avoids “humiliation” for Putin. Italy has submitted a four-point peace plan to the United Nations. But the US remains resolute, with support for the war still receiving overwhelming public support.

“The word ceasefire is on everyone’s lips. The problem is we are now entering a long and difficult part of the war itself,” said Lawrence Freedman, professor of war studies at King’s College London. “My worry is the Americans will lose interest. At some point Putin could offer a ceasefire, and people’s ears will prick up -- but it is a trap for Ukrainians.”

At Davos, European Parliament President Roberta Metsola earned a round of applause for a speech that called for an end to talk of appeasement.

“This is not the time to talk about face-saving for Russia,” she told the gathering.

Amid the gloom, some said there are still benefits to the WEF’s gathering, and simply getting together in a room.

“The risk of a food crisis has gone right up the agenda,” said Anne Richards, chief executive of Fidelity International. “You’ve definitely seen some of those conversations progress. We’re not out of the woods yet but I think we have made real progress on what it is we need to do to make sure that food and the food chain doesn’t get weaponized in time of war.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)