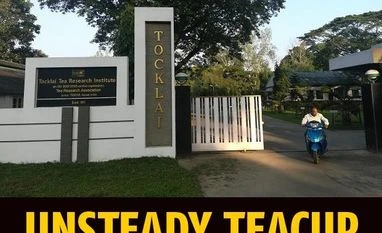

Ceramic cups filled with tea of different varieties and in varying shades of brown are laid out alongside pots brimming with leaves and powder at the office of Romen Gogoi, the taster at the world’s oldest and largest tea research centre. He has already given me a lowdown on how coordinated research at various stages — from plucking of the tea leaf to the final packaging — at the Tocklai Tea Research Institute in Jorhat, Assam, has been guiding the industry to produce quality beverage.

As he sips and spits out spoonfuls on a spittoon and explains how an expert has to retain taste buds, thousands of which are weakened by food habits, I imagine this demo would soon be a highlight when a plan to turn the century-old centre into a tourism hub comes to fruition.

Taster Romen Gogoi gives a demonstration of sampling different varieties of tea

Last month, the Assam government offered funds worth Rs 500 million to revamp the 39-acre leafy campus within seven months. Named after a local rivulet, the Tocklai institute, with its heritage buildings, laboratories, workshop, factory and guest house that has hosted royal dignitaries and political figures, is a natural addition to an emerging tourism circuit in a district that has a clutch of colonial era tea estates and bungalows. Yet, employees at Tocklai fear that such an initiative leaves unresolved an acute institutional crisis — lack of adequate funding from the Central government.

A visit to the institute, as it stands, is like stepping into a museum in a tropical forest. From canopied rain and fruit trees to coconut groves, hyacinth-filled ponds and a stretch of tea plants, the panoramic greenery is only separated by concrete pathways leading to new auditorium and directorate buildings, the 88-year-old white colonial guesthouse, and Assam-type departmental blocks, canteen, officials’ bungalows and staff quarters.

Beyond its scenic charm, Tocklai’s tourism potential is obvious to the average tea enthusiast.

One may chance upon curious nuggets. For instance, milk-rich northern states such as Punjab and Haryana record higher consumption than Assam and West Bengal, thanks to the preference for the more economical black tea in the east. And to trap harmful pests, yellow polythene and contraptions with glues to attract specific insects are mounted atop tea plants in estates. One may simply learn about the medicinal properties of tea from the taster, or discover how the tea leaf in China — the leading producer, ahead of India — appears pygmy-sized compared to the Assamese leaf.

The makeover plan, according to reports, will convert parts of the campus into tourist spots to showcase local culture, besides allowing visitors access to its entomological museum, the different stages of processing, samples of tea at the tasting unit and opening a tea museum.

Technical officers inside a lab at the institute’s entomology department

Prabhat Kumar Bezboruah, chairman of the Tea Research Association (TRA), the parent organisation of the institute, says, “The tea tourism project is a welcome initiative, but it may only generate an extra Rs 10 million. We are short by Rs 90-100 million every year, so unless the Central government shoulders its responsibility, we may not be able to continue running the institute.”

The institute, which caters to three-fourths of the Indian tea industry, gets 51 per cent of its expenditure from member companies, points out Tocklai director A K Barooah. Its advisory network carries out transfer of technology to cover 1,076 tea estates across 341,049 hectares in the north and south riverbanks of the Brahmaputra, Upper Assam, Cachar, Tripura, Dooars, Darjeeling and Terai.

“We have a projected budget of Rs 280-300 million annually, but government support is lacking. From the industry we have received around Rs 170-200 million, so if we don’t get the deficit, it will lead to problems,” he says.

Initiatives such as attracting tourists or plans to set up a training and research centre to cater to the R&D needs of small growers are meant for self-generation of funds, but won’t suffice.

“We are running largely because of industry support. We have had little government support since 2012. Recently, apart from project money we did receive Rs 115 million from outstanding dues, which helped us make payments. Else, we were struggling to clear statutory dues of retired employees,” Barooah adds.

Although Assam is synonymous with tea, until less than two centuries ago it was a secret potion of a local tribe near Jorhat. For ages, the Singphos had been drinking a handmade, wood-pounded medicinal decoction known as falap, a smoked bamboo tea. Two Scotsmen, Robert C Bruce and his brother, Charles, are credited with kick-starting the tea revolution in Assam. In 1823, the former met a native, Maniram Dewan, and through him came in touch with a tribal chief who showed him tea plants growing in the wild. Robert Bruce died a year later, before he could start plantation — a dream later realised by his brother.

he British began to consider R&D in Kolkata (then Calcutta) in the 1890s, and between 1905 and 1910 ran a one-room facility at a garden, 6 km from Tocklai. Organised tea research began in 1911 with the setting up of the Tocklai Experimental Station. The TRA was formed in 1964, and in 2014, the centre was renamed Tocklai Tea Research Institute.

The institute, which has had a stellar record and led revolutionary efforts such as popularising the crush, tear, curl (CTC) method of processing black tea, as against the orthodox style, is now focused on projects that help meet industry challenges, says Barooah. The challenges include sustainable production and quality, increasing cost of production, declining price realisation, shortage of workers and climate change.

The institute and its outstation branches have an employee strength of 196, including about 100 executive and junior technical officers, besides administrative staff, says Barooah. In Tocklai alone, there are 135 personnel — until two decades ago, there were 500, say employees.

Run solely by the industry in the initial decades, the institute approached the Centre in 1963 to fund it partially. The government agreed to the demand after the formation of the TRA. The TRA was adopted as one of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research’s (CSIR) group of laboratories. From April 1990, the TRA was linked to the department of commerce under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry and the Tea Board of India for grants-in-aid.

As of April 1, 2018, 66 per cent of Tocklai’s budget is met through funds from the industry members’ subscription/internal fund generation and the rest from the commerce ministry through the tea board.

TRA’s Bezboruah also questions the quality of research. He says, “There are good scientists, but the majority of them are non-Assamese. The locals, who have joined of late, are better. But some locals who have spent decades at the centre have victimised the outsider.” An officer at Tocklai, when asked, denies facing any obstacles from the Assamese employees. The officer says, “Our work is project-based, and we should take pride in a century-old institute. But there is drastic cut in manpower with positions remaining vacant after retirements of some.”

When the 10th and 11th Five-Year Plans (2002-12) were in force, the government offered 80 per cent of the grants whereas the industry contributed 20 per cent. But since the 12th plan (2012-1017), the Centre’s contribution was reduced to 49 per cent. “Tocklai’s brand name will not result in R&D funds, although it may help tourism,” says an engineer at the centre. “Ideally there should be government takeover with 100 per cent funding. We need a structural change as sufficient research cannot be sustained under the present system.”

Tea planters feel that regardless of the question of Tocklai’s ownership, the industry has to remain a collaborator in research work as it is the direct beneficiary.

Raj Barooah, director of Jorhat-based Aideobarie Tea Estates, stresses that the institute was started by the industry whose subscription fee has also gone up over the last two years. He says: “We take a lot of help from Tocklai. Every other thing that the industry is using has its genesis or background in research carried out there. Today, most people seem to forget that.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)