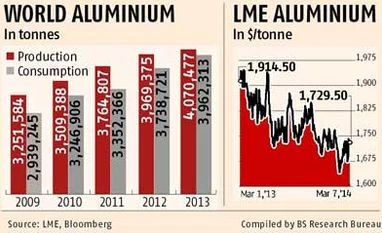

Last year, the global use of primary aluminium had risen eight per cent to 50.4 million tonnes (mt). In the last quarter of 2013, demand rose 10 per cent. The spurt, according to investment bank Barclays, shows the return of global manufacturing confidence.

As is the case with other metals, from steel to copper, China remained at the fore of aluminium production and consumption growth. Last year, however, proved disappointing for India, where production likely contracted 4.7 per cent to 1.6 mt. National Aluminium Company (Nalco) exercised restraint on smelter capacity use and Vedanta Aluminium remained engaged in an unending struggle to procure alumina to feed its Jharsuguda smelter in Odisha. Much in contrast to China, where demand rose 10 per cent, in India, it declined, owing to a disappointing performance in the manufacturing sector. Indian annual consumption was 1.8 mt. Local prices are derived from London Metal Exchange (LME) rates, plus freight and duties.

When 2013 world production, rising 4.5 per cent to 49.631 mt, trailed consumption by 726,000 tonnes, why should the three-month LME price be as low as $1,725 a tonne? The principal market spoiler is the rise in global inventory to 15 mt, including a record 5.5 mt with LME-registered warehouses, where stocks have increased fourfold since the 2008 financial crisis. It is also stocked in 'stealth shades' in and outside China. The huge inventories are due to investors borrowing money at very low interest to buy for storing in warehouses cheaply. Financing deals in aluminium continue to gain currency. The prevailing system allows investors to sell the metal immediately, making use of the future price structure. As traders have seized aluminium for collateral in financing deals, the physical market outside China has seen a deficit. According to Barclays, the deficit this year would rise to 1.1 mt from 726,000 tonnes in 2013. It is arrived at after adjusting for surplus in China. Principally due to China, global production could rise despite contraction in output in Europe, the US and Australia, as groups there are left with no alternatives to switching off high-cost smelters to protect profits.

Nalco Chairman Ansuman Das says, "Prices remaining stubbornly low, high premium rates have come to the rescue of a lot of smelting capacity across the world. It will be interesting to watch how premium rates are impacted by the proposed LME changes to warehouse management."

There are two conflicting views on why queues have remained long. Industrial companies complain many warehouses owned by banks and trading houses are run in a way that consumers are left with no choice but to pay rent through a prolonged period, as well as high premiums. LME, however, says bunching of cancelled warrants, leading to long queues, is primarily responsible for high premiums. Whatever the truth, hardening of premiums is a commentary on the exchange's oversight of warehousing management. Under regulatory and legal pressure, LME had to initiate market consultation on ways to reform its warehousing system. Two LME reforms that will have a major bearing on premiums relate to reducing warehouse queues to 50 calendar days and penalties in case warehouses are found to be loading-in more than loading-out. The exchange is also asking warehousing companies to moderately scale rent three per cent in April, against last year's seven per cent. The proposed reforms will undoubtedly have a cooling effect on premium rates.

Consultancy firm CRU, however, says, "We do not expect premiums to collapse, as these will be supported by improving demand, ongoing contango financing and tighter scrap supply deficits" outside China.

As is the case with other metals, from steel to copper, China remained at the fore of aluminium production and consumption growth. Last year, however, proved disappointing for India, where production likely contracted 4.7 per cent to 1.6 mt. National Aluminium Company (Nalco) exercised restraint on smelter capacity use and Vedanta Aluminium remained engaged in an unending struggle to procure alumina to feed its Jharsuguda smelter in Odisha. Much in contrast to China, where demand rose 10 per cent, in India, it declined, owing to a disappointing performance in the manufacturing sector. Indian annual consumption was 1.8 mt. Local prices are derived from London Metal Exchange (LME) rates, plus freight and duties.

When 2013 world production, rising 4.5 per cent to 49.631 mt, trailed consumption by 726,000 tonnes, why should the three-month LME price be as low as $1,725 a tonne? The principal market spoiler is the rise in global inventory to 15 mt, including a record 5.5 mt with LME-registered warehouses, where stocks have increased fourfold since the 2008 financial crisis. It is also stocked in 'stealth shades' in and outside China. The huge inventories are due to investors borrowing money at very low interest to buy for storing in warehouses cheaply. Financing deals in aluminium continue to gain currency. The prevailing system allows investors to sell the metal immediately, making use of the future price structure. As traders have seized aluminium for collateral in financing deals, the physical market outside China has seen a deficit. According to Barclays, the deficit this year would rise to 1.1 mt from 726,000 tonnes in 2013. It is arrived at after adjusting for surplus in China. Principally due to China, global production could rise despite contraction in output in Europe, the US and Australia, as groups there are left with no alternatives to switching off high-cost smelters to protect profits.

Nalco Chairman Ansuman Das says, "Prices remaining stubbornly low, high premium rates have come to the rescue of a lot of smelting capacity across the world. It will be interesting to watch how premium rates are impacted by the proposed LME changes to warehouse management."

There are two conflicting views on why queues have remained long. Industrial companies complain many warehouses owned by banks and trading houses are run in a way that consumers are left with no choice but to pay rent through a prolonged period, as well as high premiums. LME, however, says bunching of cancelled warrants, leading to long queues, is primarily responsible for high premiums. Whatever the truth, hardening of premiums is a commentary on the exchange's oversight of warehousing management. Under regulatory and legal pressure, LME had to initiate market consultation on ways to reform its warehousing system. Two LME reforms that will have a major bearing on premiums relate to reducing warehouse queues to 50 calendar days and penalties in case warehouses are found to be loading-in more than loading-out. The exchange is also asking warehousing companies to moderately scale rent three per cent in April, against last year's seven per cent. The proposed reforms will undoubtedly have a cooling effect on premium rates.

Consultancy firm CRU, however, says, "We do not expect premiums to collapse, as these will be supported by improving demand, ongoing contango financing and tighter scrap supply deficits" outside China.

)